In the footsteps of Caribbean rodents

Rodent and human teeth. An exclusive investigation conducted in Puerto Rico by a team of paleontologists, geologists, and biologists who are examining 30-million-year-old clues to solve one of science's great mysteries...

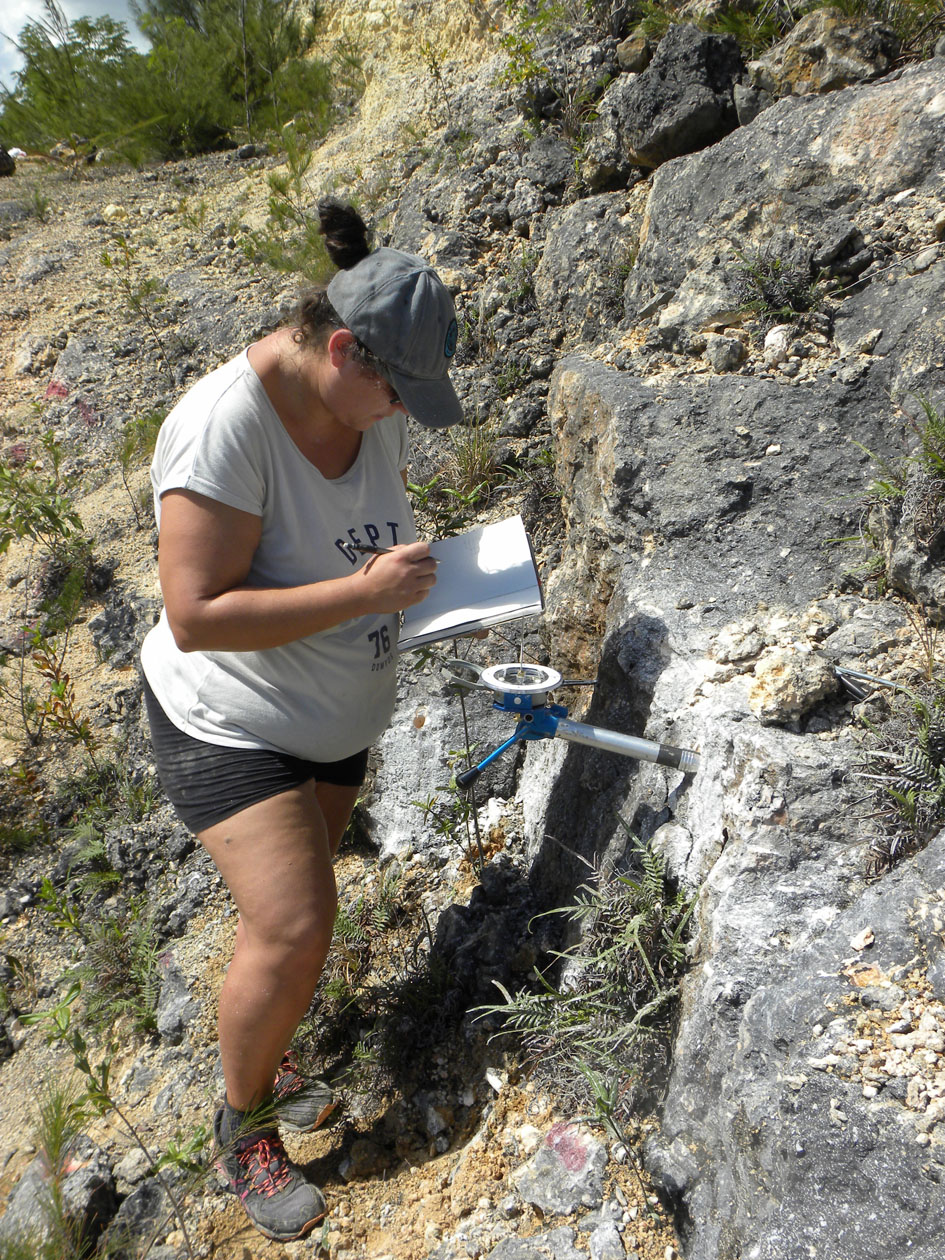

700 kilograms of soil to sift through and examine 5 grams at a time. That's the scale of the project that Pierre-Olivier Antoine and his fellow paleontologists have undertaken on the island of Puerto Rico. It's a painstaking task with an ambitious goal: to understand how the first land mammals arrived in the Caribbean.

"This question is one of the most challenging mysteries in natural sciences today," emphasizes the paleontologist fromthe Institute of Evolutionary Sciences in Montpellier. One mystery hides another: how were these islands formed from a geological point of view? "We have already defined the broad outlines, but the contribution of paleontology allows us to refine the scenarios, in particular to specify the timing," explains Philippe Münch, from the Montpellier Geosciences Laboratory. Accompanied by paleontologist Laurent Marivaux fromISEM, the two Professors an international team in Puerto Rico in February 2019 to search for clues that would help them advance their investigation.

– 30 million years

But why Puerto Rico? "A Puerto Rican paleontologist published an astonishing discovery there in 2014: a fossilized rodent incisor." While this discovery in itself is not exceptional, its analysis revealed many surprises. "It appears to belong to a line of rodents originating in South America, and has been dated to nearly 30 million years ago!"

This would mean that the rodents in question had migrated from South America to the Caribbean during this very distant period. That's when the team of detective researchers decided to go there. After sifting through the soil tirelessly, they were lucky enough to find three more teeth, molars that were "easier to identify with certainty than an incisor," explains Pierre-Olivier Antoine. Their age? Thirty million years. This confirms the theory that these rodents have been present in the Caribbean since ancient times.

Land route

"These are the oldest known rodents in the Caribbean, which are close extinct cousins of chinchillas, viscaches, and other pacaranas currently found within the chinchilloids, a group of rodents found exclusively in South America," explains Laurent Marivaux. This is a valuable clue for his fellow geologist. Because if these rodents were able to make the journey, it means there was a passage... "This means that at that time there was a more or less continuous land route between the continent and the islands, a land route or even a myriad of closer islands that would have allowed them to reach Puerto Rico and the Greater Antilles." The team of geologists is therefore actively searching the islands and the Caribbean seabed for clues to the existence of these ancient islands that have now disappeared.

This scenario is becoming clearer as more fossils are discovered. Biologists atISEM, including Pierre-Henri Fabre, have shown by studying the genetic variations of these rodents that there were several waves of arrivals in the Caribbean. "There would therefore have been several periods when the continental landmasses allowed this passage," explains Philippe Münch. These ancient islands must therefore have disappeared under water and re-emerged several times. A decidedly complex geological history.

Well-kept secrets

Another clue should soon reinforce these hypotheses: "We are awaiting the results of ancient DNA analyses by the end of 2020." Not on these famous teeth, which are far too old to yield usable DNA, but on more recent fossils of descendants of these early settlers, discovered during the last campaign in February 2020.

And the investigation doesn't stop there. Always on the lookout for new evidence, paleontologists continue to sift through the rocks. Among these tons of rock, other fossils should soon reveal their mysteries. "Puerto Rican rodents have not yet revealed all their secrets," says Pierre-Olivier Antoine. This is enough to keep paleontologists on their toes...

This research received support from the French National Research Agency Research ANR),GAARAnti program(ANR-17-CE31-0009), led by Philippe Münch (Geosciences Montpellier, University of Montpellier) [INSU], whose partner for paleontology and biology isthe Institute of Evolutionary Sciences in Montpellier [INEE].