Dengue virus in mainland France: what can we expect this year?

Vacations don't always go as planned... In our series "A week in hell!", we break down what can go wrong, from increased motion sickness when leaving on vacation to mosquito bites that can now transmit tropical viruses, not to mention the little-known microbiological dangers of hotels, "traditional" sunburn, or the unexpected dangers of gardening, if you thought you were going to stay quietly at home.

Yannick Simonin, University of Montpellier

According to all specialists, 2022 was an exceptional year in mainland France in terms of the circulation of arboviruses, viruses transmitted by blood-feeding arthropods such as ticks and mosquitoes.

Is this year a sign of what lies ahead? Or is it more of an anomaly for our country, which is not usually affected by these viruses, which are considered rather "exotic"?

2022, a record-breaking year in mainland France

Flashback. In the middle of summer 2022, the first "indigenous" case of dengue transmission was reported in France. This adjective refers to an infection detected on national territory, without the patient having previously traveled to an infected area. Unlike cases "imported" from abroad, this means that the virus is circulating within the country.

This was not particularly surprising: dengue fever, the most widespread arboviral disease in the world, affecting between 100 and 400 million people each year, has already been responsible for indigenous cases in mainland France in recent years. The virus had been detected in the Alpes-Maritimes, Var, Bouches-du-Rhône, Hérault, and Gard departments, with a total of around 30 cases since 2010. So initially, there was no real cause for concern.

But 2022 did not go as planned, and there was a string of local cases. Nine episodes of local dengue transmission were recorded, totaling 66 cases in the regions of Occitanie (12 cases), Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur (52 cases), and Corsica (two cases). In addition, the virus spread to new departments where no cases of dengue fever had ever been identified, such as Haute-Garonne, Hautes-Pyrénées, and Pyrénées-Orientales.

Sixty-six indigenous cases may seem like a small number, but in a single year, this represents more than double the number of cases recorded in 12 years since the first indigenous case of dengue fever was identified in France in 2010 in the Alpes-Maritimes department.

However, dengue fever is a disease that should not be taken lightly.

Dengue fever, a potentially serious disease

Although dengue fever is asymptomatic in a large proportion of cases (between 50% and 90%, depending on the study), in approximately 1% of cases it can develop into a potentially fatal form known as "hemorrhagic" dengue, which is accompanied by multiple bleeding, particularly gastrointestinal, skin, and cerebral bleeding.

[More than 85,000 readers trust The Conversation's newsletters to help them better understand the world's major issues. Subscribe today]

In other symptomatic individuals, the disease mainly manifests itself through symptoms similar to those of the flu: fever, headache, muscle pain, etc. It is estimated that each year, 500,000 people worldwide are hospitalized for severe forms of the disease, resulting in between 10,000 and 15,000 deaths. Beyond this cost in human lives, the treatment of the disease has a definite cost for the community.

Limiting the number of cases is important because the disease can spread with every mosquito bite.

What means of control?

When a mosquito vector bites an infected host, the virus multiplies in its body. During the next bite, it will pass into the bloodstream of another person, where it can be picked up by another mosquito, and so on.

The best way to limit the spread of an infection outbreak is therefore to combat the main vector of this virus: Aedes albopictus, better known as the tiger mosquito.

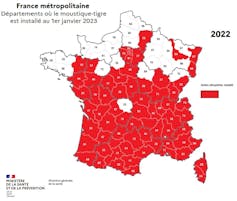

This is a very complicated task, as the range of this mosquito has been steadily expanding in France in recent years, significantly increasing the number of departments at risk.

Each identified household requires the implementation of a fairly heavy infrastructure to break the cycle of virus circulation in the human population: mosquito control operations near detected cases (to eliminate adult mosquitoes and their larvae), awareness-raising campaigns targeting the general public and healthcare professionals, door-to-door surveys conducted in collaboration with regional health agencies (ARS), Santé publique France, and mosquito control agencies (Altopictus or the Interdepartmental Mosquito Control Agreement).

What can we expect in the coming years?

It is very difficult to predict the circulation of arboviruses, as their transmission cycle is influenced by multiple factors.

It is therefore difficult to know whether 2023 and the following years will be similar to, or worse than, 2022. It is also difficult to predict which arbovirus—dengue, Zika, or chikungunya—will take center stage. However, as dengue is the most widespread arbovirus on the planet, there is a strong likelihood that we will see more and more cases of this disease in mainland France in the coming years.

One thing is certain: it is now clear that we can expect an increase in cases of arboviral transmission in mainland France over the coming summers. This is particularly true given that the exceptional situation observed in France last year is not an isolated case on a global scale.

In the Americas, 2.8 million cases of dengue fever were identified in 2022, more than double the number of cases reported in 2021. And for some countries, 2023 is already synonymous with an unprecedented dengue epidemic: Peru is experiencing the most intense wave since the disease reappeared in the country in 1990.

Another worrying indicator is that the World Health Organization is preparing for the possibility that the El Niño phenomenon, predicted for 2023 and 2024, could increase the transmission not only of dengue fever, but also of other arboviruses.

Finally, climate change will also impact the proliferation of mosquitoes that carry these diseases by extending their period of activity, which currently peaks between May and September. In addition, high temperatures promote the multiplication of viruses in mosquitoes and therefore their transmission.

Surveillance networks at the limits of their capacity

Although it is an all-time high, the number of dengue cases recorded in 2022 is likely to remain very limited compared to what we can expect in the coming years. In addition, France will host major sporting events in the coming years, including the Olympic Games in 2024, which could contribute to increasing the spread of arboviruses.

Faced with the emergence of these arboviral diseases, France has set up active surveillance networks. These networks bring together experts with different skills (veterinarians, clinicians, entomologists, researchers), all of whom contribute to a better understanding of these viruses.

However, last year's explosion in cases put them under severe strain locally, as did mosquito control networks, which are operating at full capacity. This situation highlights the need for greater investment in these areas. We must start preparing today so that we are in the best possible position to control future epidemics. In this sense, 2022 is a warning that we must all take seriously...

Yannick Simonin, Virologist specializing in the surveillance and study of emerging viral diseases. University Professor, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.