Blank and invalid votes, a voice with little resonance

In light of this election, which was atypical and turbulent to say the least, both in terms of the campaign—marked by a series of twists and turns with domino effects—and its outcome—the disqualification of traditional parties and the rise to power of a new political movement, foreshadowing a reshaping of the political landscape—the attention paid to blank and invalid votes (VBN) may seem misplaced.

Aurélia Troupel, University of Montpellier

However, with more than 4 million blank or invalid ballots cast, this phenomenon is not as insignificant as it may seem in this election. For the first time, the figures for blank and invalid votes were very quickly included in the election night commentary; for the first time, too, they were announced shortly after the abstention rate, thus completing the overview of (non)participation in the election.

Out of the shadows

Several factors explain why blank votes emerged from the shadows of abstention. First, there is the economic climate. The call for blank votes, or at least the discussions within certain political parties and movements following their elimination in the first round, served as a reminder that blank votes could be an alternative, even when the second-place candidate belongs to the National Front. This alternative was confirmed, or at least chosen, by a large number of voters, as evidenced by the record rate recorded on May 7, despite an intense campaign between the two rounds encouraging voters to use their ballots "wisely" and block the path of the far right.

Secondly, as significant as the percentage of blank ballots was in the second round, the issue of blank voting was already receiving media coverage, albeit very modest. Since the law of February 21, 2014, leading to the separate counting of blank and invalid ballots, a few articles have addressed the issue of their true recognition (so that they are considered as votes cast and count in the calculation of candidates' scores), fueled by a more general reflection based on the work of Jérémie Moualek.

But this is the first time that, in order to understand what happened in this second round, blank and invalid votes seem to have to be taken into account to such an extent, alongside abstention and other electoral choices. While the electoral offer, in the first and even more so in the second round, can largely explain the volume reached by blank and invalid votes, the motivations and meanings of blank votes remain relatively unknown.

The aim of the ongoing research project, entitled "The ignored voter: blank and invalid votes," which seeks to establish a quantitative sociology of these voters, and some of whose results we present briefly here, is precisely to shed light on these issues.

For the time being, the presentation of three questions from the survey conducted after the first round by Respondi already highlights some elements of how blank and invalid votes are perceived by the "voters" interviewed below. Despite the methodological precautions taken, the results presented are not representative of the French population, as only panelists who were registered to vote and who voted in the first round were surveyed. This means that those who abstained from voting in the first round were not included in our survey. Nevertheless, this remains the only way to capture these voters and, more generally, to collect data on blank and invalid votes.

Blank votes, a means of expression...

What meaning should be given to blank ballots? And to invalid ballots? If dissatisfaction seems obvious, or even protest, how can the analysis be refined? How do they compare to other forms of electoral behavior?

To find out, two separate questions were asked to panelists. The first has a rather positive connotation:

“What do you think is the best way to make elected officials understand your expectations for change?”

The other, on the contrary, is rather negative:

“And how can you express your frustration? What is the best way?”

In order to avoid influencing responses, precautions were taken regarding the order and wording of questions and answers. First, regarding order: the questions presented below are the first to mention blank and invalid votes in the possible answers, and they appear after questions about the campaign and a more traditional question about voting. Particular attention was also paid to the wording of the questions: they are taken verbatim from sentences formulated by other respondents in a previous study.

The same concern guided the choice of responses: on the one hand, blank votes and invalid votes were separated in order to assess their respective importance; on the other hand, they appeared among other options such as "voting for a minor candidate," "abstaining," and "you don't want change/you're not fed up."

In both cases, blank votes came out on top (Table 1 below). They even eclipsed abstention and votes for the far right. To make elected officials understand their expectations for change, the majority of respondents chose blank votes (24.9%), followed by votes for a minor candidate (20.3%) and votes for the far right (17.9%)—representing a total of nearly two-thirds of responses. The "other" category, which was also frequently chosen, was reworked based on the details requested from panelists.

Grouped together in these sub-themes, the qualitative responses highlight the spontaneous attachment to the act of voting (for 53% of those who answered "other"), as well as to voting for the candidate of their political persuasion (12.2%). When it comes to change, this seems to be perceived more as something that can be achieved through the ballot box—whether by casting a blank ballot, voting for a minor candidate, voting for their political camp, or voting for the far right. Indeed, for those respondents who vote, abstention does not appear to be a means of getting this message across.

On the other hand, when it comes to expressing their dissatisfaction with elected officials, the trio of "blank vote/vote for the far right/vote" for a minor candidate is somewhat shaken up. The blank vote continues to stand out clearly from the other options, but this time it is the vote for the far right that rises to second place. Far behind are voting for a minor candidate and abstention.

The difference between the expression of change and that of frustration is shaking up the lines for these options: voting for minor candidates loses several points while abstention gains points. Even the "other" option decreases (-5 points); with the act of voting—in whatever form—being mentioned less often by the "other" group than previously. Only 50.8% of panelists who chose this response refer to voting.

On the other hand, proportionally more of them opt for a more direct and less conventional expression (dialogue with elected officials, demonstrations, revolution, etc.). Finally, nearly 10% of these "others" express a form of defeatism with responses such as "none," "they don't understand us," "I don't see how to do it," or advocating widespread abstention.

… yet rarely heard

While respondents see blank votes as the main way to convey their expectations for change or their exasperation, they do not believe that elected officials hear their message. The question asked immediately afterwards, "What do you think has the most impact on politicians?", revealed significant variations. For more than a quarter of the panelists, voting for the far right has the greatest impact on elected officials, followed by "nothing." Abstention, which had been fairly low until then—probably due to the recruitment of respondents who voted in the first round—increased, while blank votes were relegated to fifth place, behind protests.

Once again, voting for the far left and, above all, spoiling one's ballot paper are far behind in the responses recorded. Surprisingly, blank votes completely supplant spoiled votes. The latter do not really manage to gain ground alongside blank votes, despite their more assertive protest dimension (whether in the form of scratching out the ballot paper or the annotations that are sometimes made on it). Although there was a slight increase in the number of blank votes in response to the question about frustration, blank votes still had virtually no support among respondents after elected officials (1.9%). More channeled and more in line with democratic expectations, blank votes appear to be more legitimate in the eyes of respondents for expressing their expectations on the two dimensions tested.

Another lesson from these initial results is the vote for minor candidates. In these times of calls for tactical voting, these "minor" ballots, which are also rarely studied, are seen by respondents as a way of sending a message. On the evening of the first round of the presidential election, the votes scattered between Jean Lassalle, Jacques Cheminade, and François Asselineau totaled nearly 830,000... almost as many as the VBN, without a campaign (950,000).

All these factors argue for a broadening of the focus from which electoral behavior is understood. While abstention and Front National votes must obviously continue to occupy a central place in analyses due to their importance and significance, other behaviors—particularly blank votes—also deserve attention. On the one hand, this would provide a better understanding of the different nuances of protest against the political system and reveal any shifts from one form to another. On the other hand, it would fuel the increasingly recurrent debate on the recognition of blank votes.

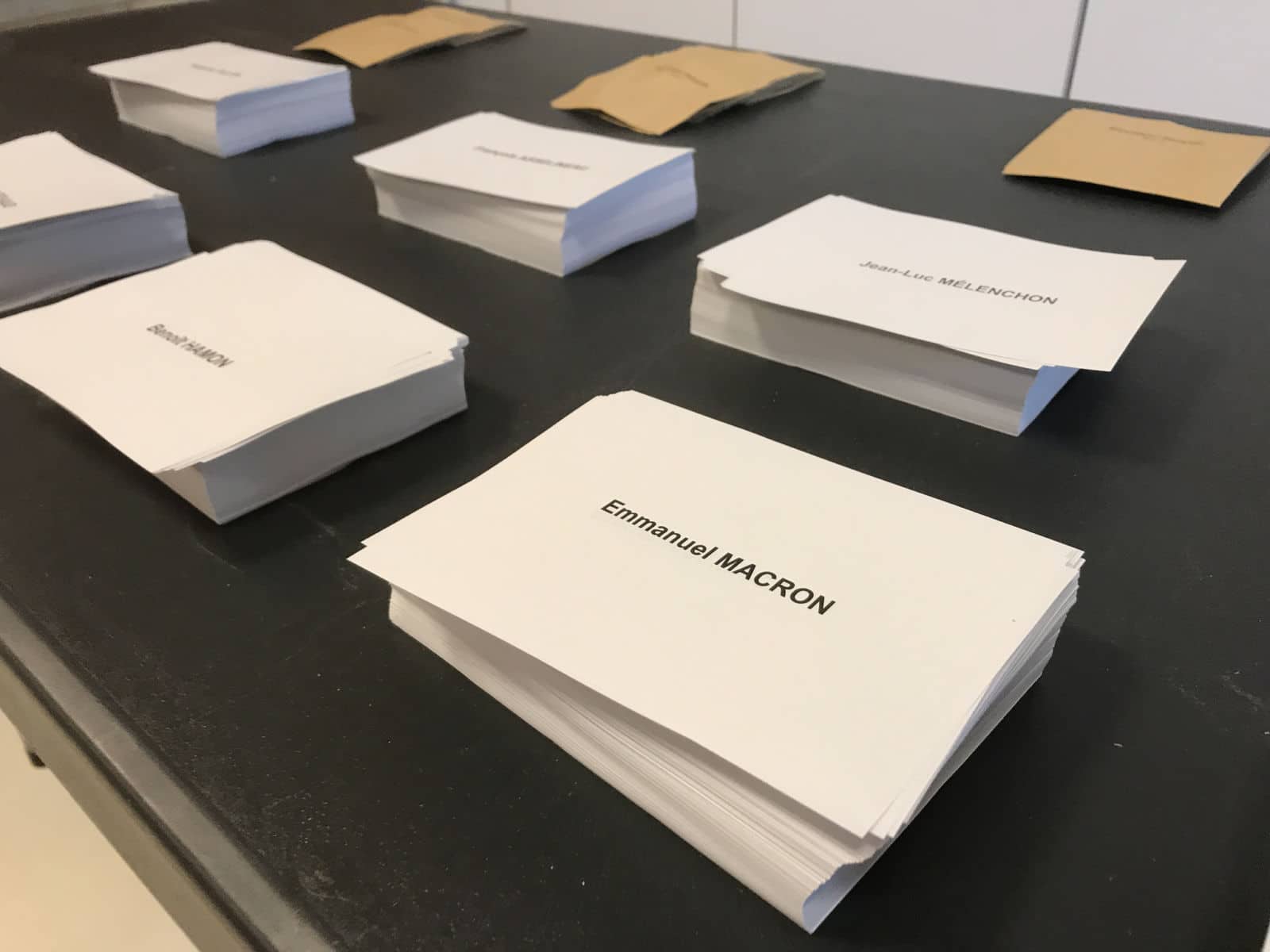

![]() Methodological note: The survey was conducted in partnership with Respondi (thanks to J. Ruiz for giving me access to the field and to the Respondi team), which distributed the questionnaires to its online panelists (of the 4,706 people surveyed, 4,424, registered on the selected lists, were retained). The first-round survey was conducted between May 3 and 6, 2017, in order to obtain a sufficient number of blank and invalid votes (151 for the April 23 election). The other respondents were then recruited proportionally, so as to approximate the results ofthe first round as closely as possible.First-round vote: blank/invalid: 3.4% (+0.9 compared to the official results); Emmanuel Macron: 21.1% (-2.3); Marine Le Pen: 19.3% (-1.4); François Fillon: 13.9% (-5.6); Jean-Luc Mélenchon: 19.6% (0.5); Benoît Hamon: 7.1% (0.9); Nicolas Dupont-Aignan: 5.0% (0.5); Minor candidates: 4.5% (0.5).

Methodological note: The survey was conducted in partnership with Respondi (thanks to J. Ruiz for giving me access to the field and to the Respondi team), which distributed the questionnaires to its online panelists (of the 4,706 people surveyed, 4,424, registered on the selected lists, were retained). The first-round survey was conducted between May 3 and 6, 2017, in order to obtain a sufficient number of blank and invalid votes (151 for the April 23 election). The other respondents were then recruited proportionally, so as to approximate the results ofthe first round as closely as possible.First-round vote: blank/invalid: 3.4% (+0.9 compared to the official results); Emmanuel Macron: 21.1% (-2.3); Marine Le Pen: 19.3% (-1.4); François Fillon: 13.9% (-5.6); Jean-Luc Mélenchon: 19.6% (0.5); Benoît Hamon: 7.1% (0.9); Nicolas Dupont-Aignan: 5.0% (0.5); Minor candidates: 4.5% (0.5).

Aurélia Troupel, Lecturer in Political Science, University of Montpellier

The original version of this article was published on The Conversation.