In Perpignan, the RN also won over the middle class.

Louis Aliot's victory in Perpignan is remarkable not only because of the size of the city (121,681 inhabitants). Indeed, the victory in the second round (against the outgoing mayor Jean-Marc Pujol, Les Républicains) is exceptional for the National Rally (RN): in 2014, only Cogolin (Var) had been taken in this way, again against a right-wing list.

Nicolas Lebourg, University of Montpellier

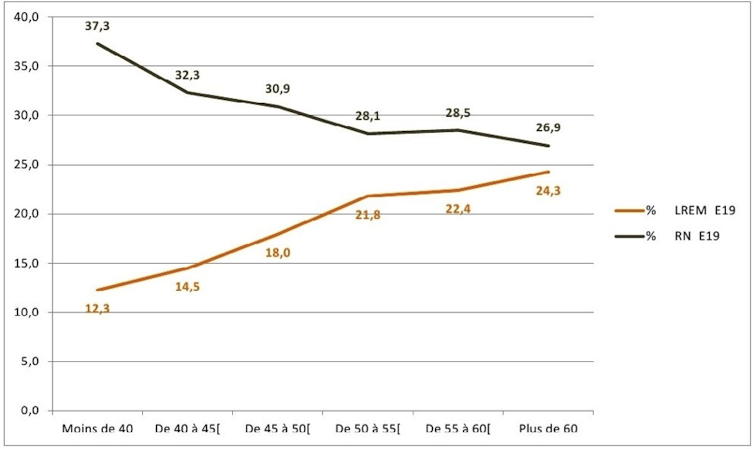

However, winning a duel requires creating a temporary alliance between citizens with divergent socioeconomic interests. The RN is normally strong among the working classes, but significantly weaker among other social groups: in the recent European elections, it won 40% of the vote among workers and 30% among households living on less than €1,200 per month (while La République en Marche won only 11%).

The capture of Perpignan is therefore particularly significant in terms of a successful merger of the right wing, achieved by surpassing the popular base of Le Penism.

The rallying of the wealthy classes

Back in 2014, Louis Aliot's list had already enjoyed notable success in Perpignan's affluent neighborhoods. In polling station No. 52, located in the Mas LLaro neighborhood of secure villas with swimming pools at the eastern end of the city, which is very upscale and lacks ethnic or social diversity, his score was 50.6%.

If another sociological factor had polarized the vote to the right, the result could have been even more significant: in the residential neighborhood of Las Cobas, polling station No. 48, with 10.6% of pieds-noirs on its electoral roll (based on dates and places of birth), voted for Aliot with 55.4%, while their more modest counterparts in the Moulin à Vent neighborhood voted less strongly for Le Pen.

A seductive liberal discourse

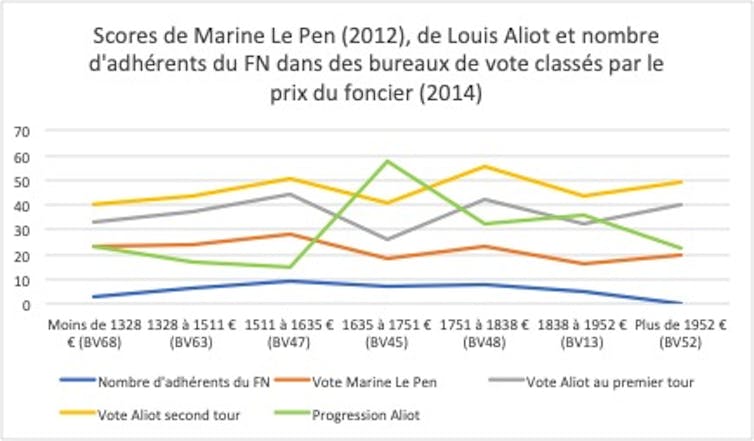

Cross-referencing the FN membership database, the price per square meter in polling stations, and the comparative scores of Marine Le Pen and Louis Aliot sheds light on one particular point:

Nicolas Lebourg, Author provided

The obvious local added value of Louis Aliot is clear, an added value that even in 2020 his opponents Jean-Marc Pujol and Romain Grau (LREM) continued to deny throughout the campaign.

The downgraded middle classes provide the bulk of activists and do have a normalizing effect on the party's presence: its score correlates with this. However, in the wealthiest category, things differ: while office 52 has no activists, "Aliotism" does have a solid base there, albeit with less room for growth than in the middle class.

The social capital cost of direct involvement with the FN (through membership) was still too high, but that did not prevent people from sharing its views.

In 2020, by investing in right-wing figures, highlighting the themes of security and prosperity, and adopting a liberal discourse far removed from that of Marine Le Pen, Louis Aliot won the day by managing to unite the working and upper classes.

A new champion

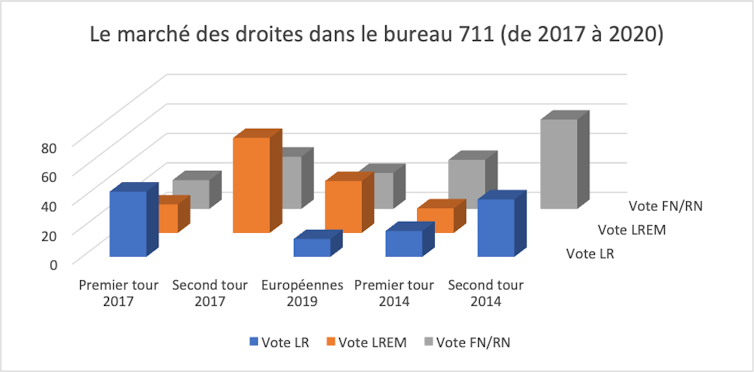

In short, Louis Aliot's list and campaign to raise his profile played the same role among the upper socio-professional categories as activists did in less affluent circles. This accommodation is not limited to the party, as evidenced by the evolution of the electoral percentages awarded by Mas Llaro (polling station 711, after the redrawing of the electoral boundaries):

Nicolas Lebourg, Author provided

This Fillonist electorate, which had overwhelmingly voted for Emmanuel Macron in the second round of the presidential election, retained its confidence in LREM in the European elections, but returned to its pro-Aliot stance in 2020.

Here we have a right wing that is seeking a champion. It does not consider the RN's program credible, as it is too anti-business, but nevertheless sees Louis Aliot as the political candidate who can deliver cultural conservatism, security and ethnic order, and economic liberalism.

This is a merger of the right wing, demonstrating how the rallying of three running mates from Romain Grau's list to Louis Aliot between the two rounds is not just a matter of personalities, but corresponds to the meeting of a political offer and a social demand.

A concrete program for security

Once elected, Louis Aliot announced that he would take direct charge of security issues. This topic has always been central to all of the FN's municipal campaigns in Perpignan, but this was the first time that the party presented a concrete program listing a series of specific measures. Although the city saw a significant drop in non-violent thefts during the previous term of office, attacks on people continue to rise, particularly assaults and battery, which have increased by 24.4% since 2013.

In January 2020, an IFOP-Semaine du Roussillon-Sud Radio poll showed that "safety of property and people" was considered a determining factor in voting by 48% of Perpignan voters surveyed.

Let's take the example of the western district of Bas Vernet, a modest area among the city's priority neighborhoods, which is indeed experiencing real security problems, particularly in the Cité des Oiseaux sector.

61% of residents in Bas Vernet Ouest considered security to be an important factor in their voting decision. And, indeed, the corresponding polling station gave 61.65% of its votes to Louis Aliot in the second round.

A convergence between working-class and affluent neighborhoods

Les Oiseaux and Mas Llaro, so different socially, thus converge in the podium of pro-Aliot polling stations. While Marine Le Pen only beat Emmanuel Macron in one polling station in Perpignan during the second round of the presidential election, this congruence enabled the construction of a political majority.

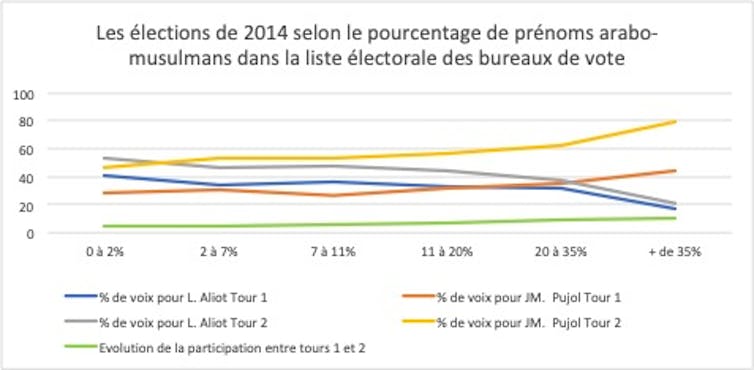

But it did not happen without divisions within the working classes. Indeed, the city has poor neighborhoods with a high concentration of people from the southern shores of the Mediterranean—particularly in the run-down old center and in the northern neighborhoods.

In 2014, it was these voters of North African origin who saved the incumbent mayor. Usually voting for the left, they rallied behind the right-wing mayor in the first round and turned out in force in the second.

The 2020 campaign was structured around a strategy aimed at manipulating this sociology. Jean-Marc Pujol's teams did everything they could to mobilize the northern neighborhoods and their Maghrebi population. Louis Aliot, for his part, avoided scaring them.

Although he launched his campaign, supported by Éric Zemmour, in a room filled with a very "bourgeois" audience, he subsequently carefully avoided the topics of Islam and immigration.

In the cities, mobilization is no longer enough

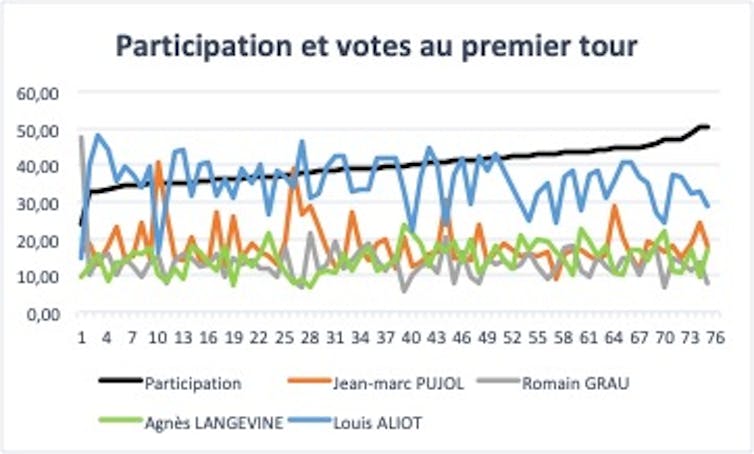

The result at the polls can be seen in the example of the Clodion polling station.

With the highest percentage of Arab-Muslim names on its electoral roll in the entire city (54.4%) and only one registered FN activist, it gave Jean-Marc Pujol his best score in 2014 (44.4%) and his best progress in the second round (up 34.7 points).

In 2020, the new city council saw its share of the vote increase by 13 points in the second round, with Louis Aliot achieving a minimum score of 20.45%. The momentum was decisive... but not enough, as it was too concentrated in certain areas: most working-class neighborhoods were not mobilized by the presence of a gentrified RN candidate.

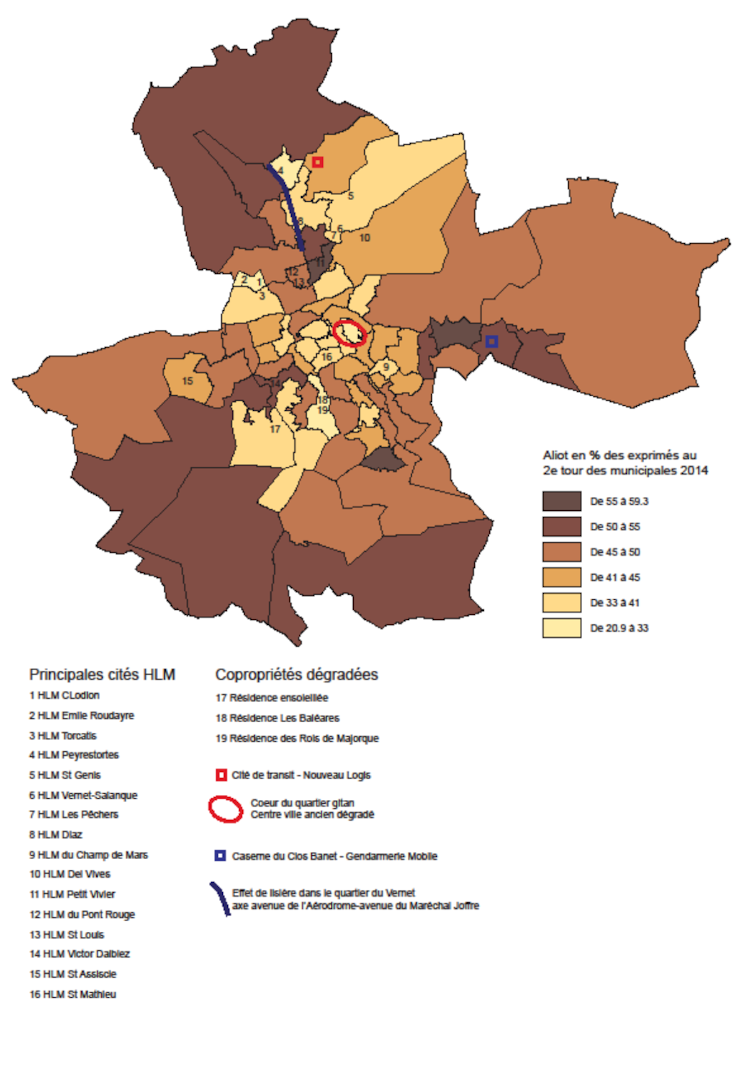

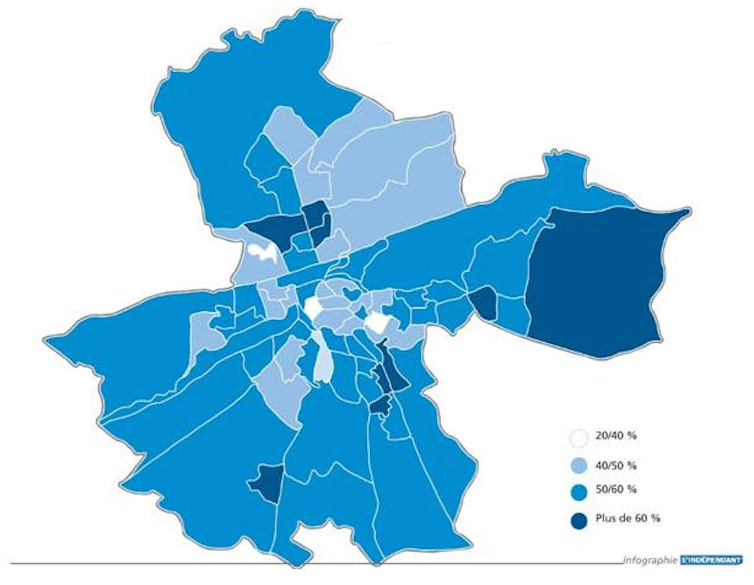

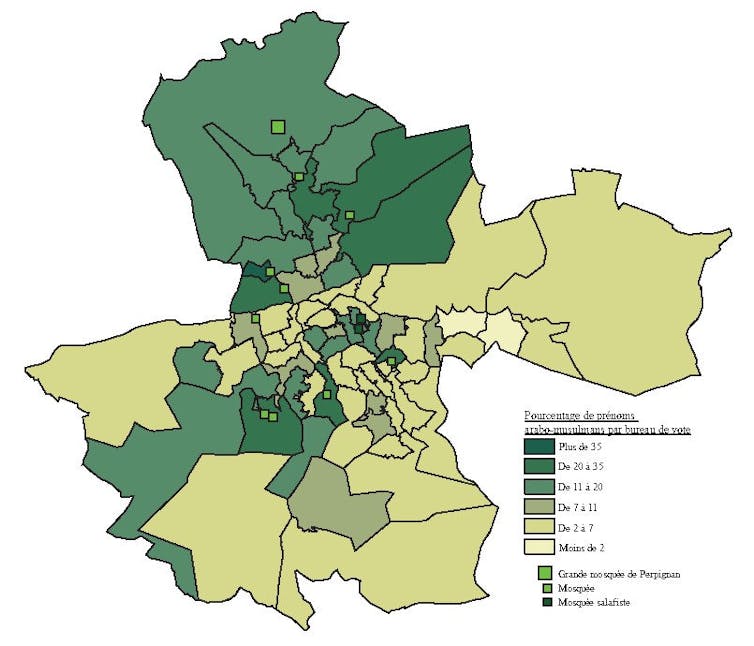

The question can be understood by comparing three maps:

- that of the Aliot vote in the second round of 2014 with the main working-class areas

- that of the proportion of Arab-Muslim first names and the presence of Muslim places of worship, both carried out by geographer Sylvain Manternach

- the Aliot vote published by the regional daily newspaper L'Indépendant the day after the second round of the 2020 elections.

Citizenship Chair, Author provided

L’Indépendant

Citizenship Chair, Author provided

The pattern that emerges is the opposite of that advocated by proponents of the "peripheral France" theory.

The RN vote did not take shape in working-class neighborhoods as a result of multicultural society, but rather around them, with peaks in affluent areas, against the multi-ethnic society deemed responsible for financial waste and insecurity, while the exhaustion of the patronage system disaffiliated working-class areas and prevented over-mobilization from taking effect this time around.

Insiders and outsiders

The natural objection to our argument would be that electoral shifts are a consequence of voting conditions brought about by the coronavirus crisis and an excessively long interval between the two rounds of voting, which demobilized entire sections of the electorate, as political scientist Céline Braconnier has shown. We can demonstrate that the issue is structural with a few diagrams.

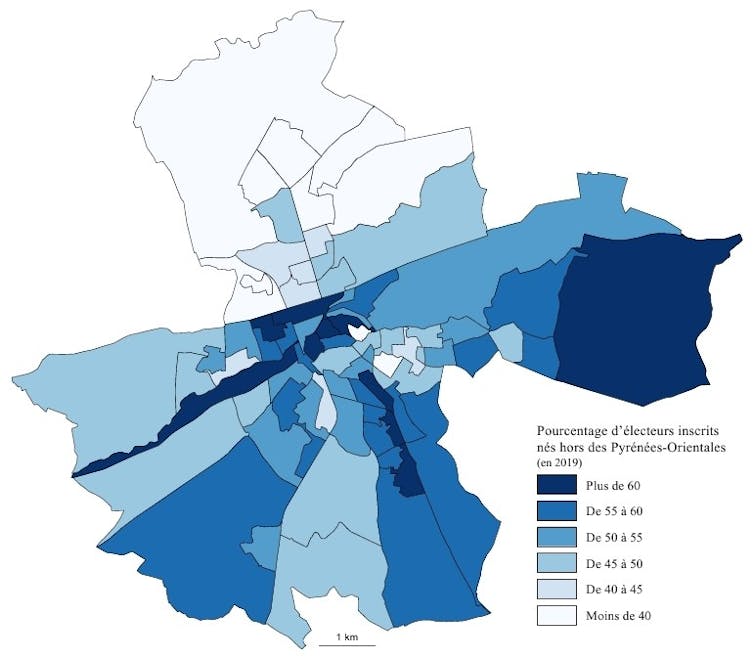

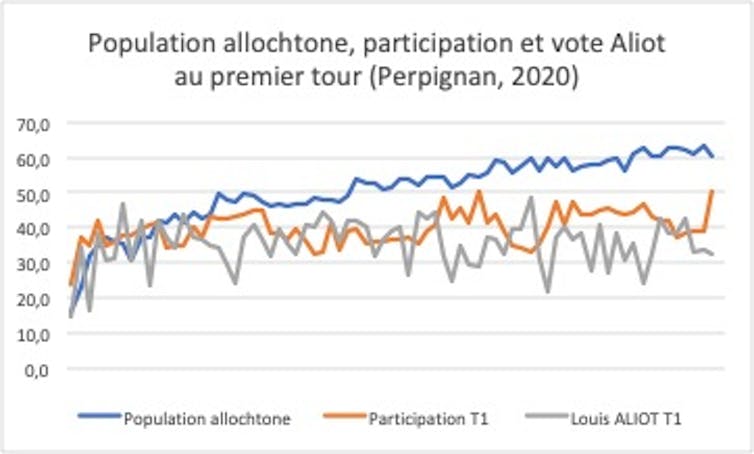

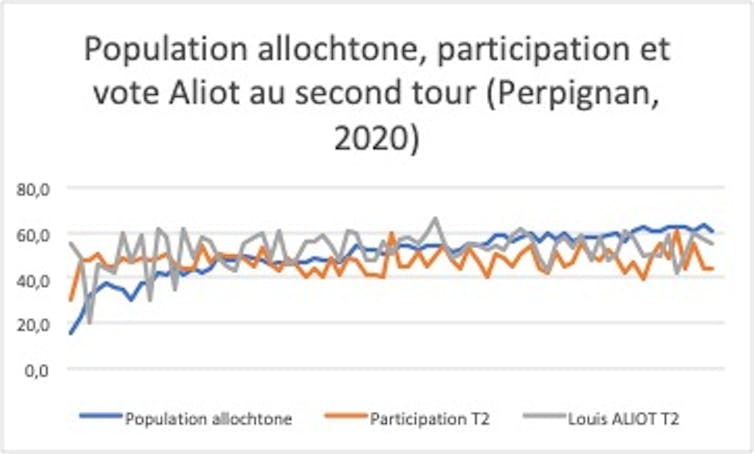

Half of Perpignan's electorate is made up of people born in the department, while the other half comes from other departments in mainland France. In everyday Perpignan vocabulary, this difference is summed up by the terms "Catalans" and "Gavatx," those who are "native" and those who come from beyond the village of Salses. These "allochtones," as non-native Perpignan residents are often called, tend to live in affluent neighborhoods:

Citizenship Chair, Author provided

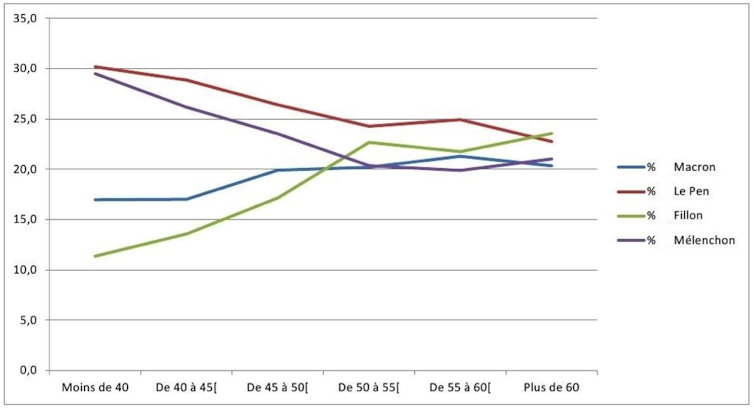

As we demonstrated with Jérôme Fourquet and Sylvain Manternach in our study on the city for the Citizenship Chair at Sciences Po Saint-Germain-en-Laye, these immigrants vote much more liberally than native-born citizens:

Citizenship Chair, Author provided

Citizenship Chair, Author provided

However, it turns out that those who are more integrated into the economic system and less integrated into the local sociocultural system were more active in the municipal elections.

If we look at the election results by ranking polling stations according to turnout:

N. Lebourg, Author provided

Then we rank the offices by percentage of foreign-born population:

N. Lebourg, Author provided

N. Lebourg, Author provided

It appears that the Aliot list initially suffered in the first round from a demobilization of the native electorate that supports it. Although it scored almost twice as many votes as Jean-Marc Pujol, this level masks a differentiated abstention rate against it, due to the greater civic integration of immigrants, who are less likely to vote for the National Rally and more likely to turn out at the polls.

Admittedly, the return of native voters in the second round enabled Louis Aliot to recover some votes, but he also owes his victory to the section of the liberal-conservative electorate from mainland France that has now turned to him, contrary to previous trends.

There has indeed been a merger of the right wing in Perpignan, ideologically, sociologically, and electorally. The coming together of the local working classes and the wealthy metropolitan classes has created a social bloc that should carry weight in the near future for the National Rally, since in the previous departmental and regional elections it had achieved excellent results in the first round by capturing the popular vote, but had been unable to attract enough support to obtain a majority in the second round. The victory in Perpignan is no accident, and the possibility of a line opening up for the RN has been raised.![]()

Nicolas Lebourg, Researcher at CEPEL (CNRS-University of Montpellier), University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.