These exotic viruses that threaten us

One of the long-term consequences of climate change is the risk of new diseases emerging that are considered "exotic" because they have been very distant from our territories until now.

Yannick Simonin, University of Montpellier

In recent years, several "indigenous" cases of this type of exotic disease have been detected in our country. This term means that the disease was contracted in the territory where it broke out, unlike "imported" cases, where the disease was brought back from travel. The distinction is important because an indigenous infection means that the virus is circulating in the territory. However, imported cases are not without risk, as an infected person can, if the vector is present, transmit the disease to others. Hundreds of imported cases of arbovirus diseases are reported in France every year.

Dengue fever, West Nile virus, tick-borne encephalitis... What are the most closely monitored emerging diseases in our country, and how are they transmitted?

Diseases that often go unnoticed

Most of these emerging diseases are caused by viruses, specifically arboviruses, which are viruses transmitted by arthropods ( arthropod-borne viruses). Whether they are insects (such as mosquitoes or sand flies, which resemble them) or mites (such as ticks), these "vectors" generally feed on blood and infect their prey during their meals.

Another distinctive feature is that these animals are initially infected by viruses. Humans become infected when an arthropod that has become infected by feeding on a domestic or wild animal then attacks them.

These viral diseases do not systematically cause illness. Thus, although the tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) transmits many human viral diseases, in most cases they are asymptomatic and go unnoticed. However, a significant proportion of people (between 20 and 30%) develop symptoms that can resemble the flu (fever, headache, joint and muscle pain) with, in some cases, an associated skin rash. Although these symptoms are usually mild, in a small proportion of cases they can lead to complications that are sometimes severe.

The main threat: the tiger mosquito

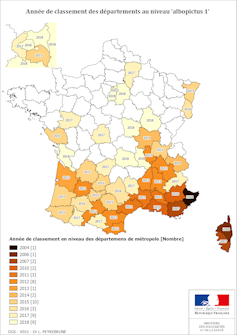

Ministry of Solidarity and Health

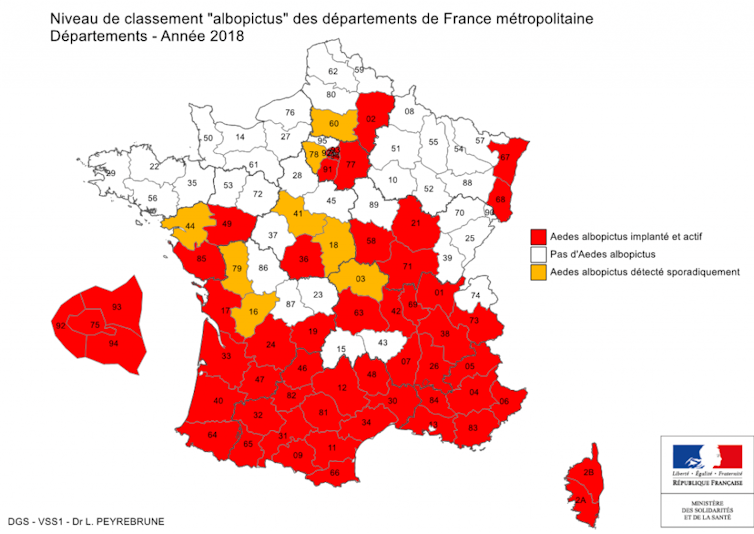

Originally from Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, the tiger mosquito has gradually colonized mainland France. It is now present in 51 departments, compared to 42 a year earlier. Northern France is no longer spared, and it can now be found in the Paris region. Experts estimate that it should spread throughout the entire country within a few years...

Among the main emerging viruses transmitted by the tiger mosquito is the dengue virus, a disease of African origin, the first cases of which were recorded in the18th century on the American continent. Well known in many parts of the world, such as Africa, Asia, and Latin America, this disease has recently become established in mainland France, particularly in the south, where around 20 indigenous cases have been recorded recently (including four in 2018).

The main problem associated with dengue fever is the risk of developing what is known as severe dengue or dengue hemorrhagic fever. Potentially fatal, it manifests itself in particular through respiratory distress associated with multiple hemorrhages. Fortunately, this form only affects a small percentage of infected individuals (around 1%).

Another virus transmitted by the tiger mosquito is the Chikungunya virus, isolated in the early 1950s on the Makonde plateau in Tanzania. Well known in the Caribbean, this virus is notable for its tendency to cause persistent joint pain, which can last for several years after the initial infection. A few occasional cases of ocular, neurological, and cardiac complications have also been reported. To date, around 30 indigenous infections have been recorded in mainland France, with the risk of localized epidemics, as was notably the case in the Montpellier region in 2014 and in the Var department in 2017.

The Zika virus is another emerging virus that has recently appeared. It made headlines three years ago, causing a massive epidemic in Latin America, mainly in Brazil. The distinctive feature of this virus, which originated in the Zika Forest in Uganda, is its ability to cause serious neurological damage in newborns. This damage is characterized in particular by a significant reduction in head circumference (microcephaly). This malformation leads to insufficient brain growth, which in turn causes disorders of varying severity depending on the extent of the damage: epilepsy, cerebral palsy, learning disabilities, hearing loss, visual problems, etc. A recent study published in the prestigious American journal Nature Medicine shows that three years after infection, children exposed to the Zika virus during pregnancy are developing new neurological disorders.

Another distinctive feature of the Zika virus is its ability to be transmitted sexually (which is unusual for arboviruses). In France, only this latter type of transmission has been identified, and no indigenous cases have been identified to date. This is probably because the tiger mosquito is a relatively poor vector for this virus, which is mainly transmitted by another mosquito, Aedes aegypti, which is very common in Latin America in particular, but has not yet established itself in our territory. However, it has been identified on the island of Madeira and its potential establishment in Europe is being closely monitored.

Ministry of Solidarity and Health

The Culex is not to be outdone

The tiger mosquito is not the only threat in the region. The "local" mosquito (Culex pipiens), found throughout the metropolitan area, can also carry viruses that are potentially dangerous to humans.

This is mainly the case with the West Nile virus. First isolated in the West Nile district of northern Uganda, it can cause severe neurological damage in humans, such as encephalitis or meningitis. Like its cousin, the Usutu virus, which is also spreading in our territory, the West Nile virus has certain species of birds as its natural reservoir, not all of which have yet been clearly identified.

See also:

West Nile and Usutu viruses: will they take root in France?

In 2018, it spread widely across Western Europe, causing the largest epidemic ever recorded on the continent: 2,083 confirmed indigenous human cases were reported (resulting in 181 deaths in a dozen countries), including France (with 27 cases recorded). According to the ECDC (European Center for Disease Prevention and Control), this epidemic affected more people than in the previous 10 years combined across Europe. This year, the West Nile virus has already been detected in 127 patients in Europe, including one case identified in France, in Fréjus.

Ticks carry equally exotic viruses.

Beyond mosquitoes, other arthropods can transmit exotic viruses. This is particularly true of ticks. These mites are best known to the general public for their ability to transmit bacterial diseases such as Lyme disease. However, they are also capable of spreading viral diseases such as TBEV, also known as tick-borne encephalitis. Found mainly in northern Europe, this disease appears to be spreading continuously.

Even more problematic is the possibility of the Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus becoming established in mainland France. First described in Crimea in 1944 and then in Congo, this disease causes massive bleeding and has a mortality rate of around 30%. The virus was first identified in Europe in 2018, with one case identified in Spain in 2018. Monitoring its spread in Europe will undoubtedly be a major issue in the coming years.

Prevention is better than cure

For most of these emerging viruses, there are currently no curative treatments or vaccines available for humans. Today, the most effective way to combat them is probably to target the vectors that spread them. This is easier said than done, as there are many factors to consider.

This is particularly true of changes in environmental conditions caused by human activity (especially rising temperatures and variations in precipitation). By affecting the geographical distribution, activity, reproduction rate, and survival of arthropods (especially mosquitoes), they alter the transmission of diseases.

Socio-economic factors are also at play: for example, increased mobility, particularly via intercontinental air travel, facilitates the spread of infectious agents. Rapid urbanization also appears to be one of the factors accelerating the emergence of these new pathogens. Indeed, it encourages the proliferation of uncontrolled water storage, which provides breeding grounds for mosquitoes that are potential vectors of viruses.

To reduce the development of mosquito larvae, it is recommended to empty all containers of standing water (especially after watering). Finally, exposed populations are encouraged to use appropriate repellents and wear loose-fitting, protective clothing to limit the risk of bites.

Improve monitoring

Faced with the emergence of these exotic diseases, most of the countries concerned, including France, have set up active surveillance networks. These networks bring together experts with different skills: veterinarians, clinicians, entomologists, researchers, etc. One example is the SAGIR epidemiological surveillance network, which monitors the circulation of pathogens in wild birds and mammals.

In order to limit the spread of potentially infected mosquito populations, mosquito control measures are carried out every year in certain European regions. The problem is that insecticide spraying can sometimes cause mosquitoes to develop resistance. Furthermore, their widespread use in urban areas is not recommended due to their toxicity.

Fortunately, in our country, the threat of arboviruses remains sporadic for the time being: strengthening surveillance networks is currently the best strategy for combating these new threats, which are difficult to anticipate.![]()

Yannick Simonin, Virologist, Associate Professor in Surveillance and Study of Emerging Diseases, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.