[LUM#16] Detoxification Champions

Every day, they drink water that is heavily contaminated with arsenic. And yet these inhabitants of the Altiplano in Bolivia do not seem to suffer from it... An enigma that epidemiologist Jacques Gardon has investigated, revealing how they may have adapted to this poison.

Arsenic, a word with an almost romantic ring to it for a substance that had its heyday at the court of Louis XIV and among the Borgia family. Yet it remains a sadly topical poison: "Consumption of arsenic-contaminated water is a public health problem affecting around 140 million people worldwide," points out Jacques Gardon. For more than five years, the epidemiologist at the HydroSciences laboratory has been studying the effects of arsenic on the health of Bolivian populations, specifically the Urus people who live on the shores of Lake Poopó.

There, the researcher found arsenic levels in the water up to 80 times higher than WHO standards. "The limit is set at 10 micrograms per liter. In some wells, we measured up to 800 micrograms per liter," he explains.But where does this arsenic come from? "It is naturally present in the earth's crust and minerals in many regions, and it can contaminate groundwater as a result of soil erosion," explains Jacques Gardon. This natural process is exacerbated in some regions by mining, as is the case in Bolivia, where miners crush arsenopyrite to extract metals and discharge arsenic, which contaminates sediments, rivers, groundwater... and wells.

Shallow wells

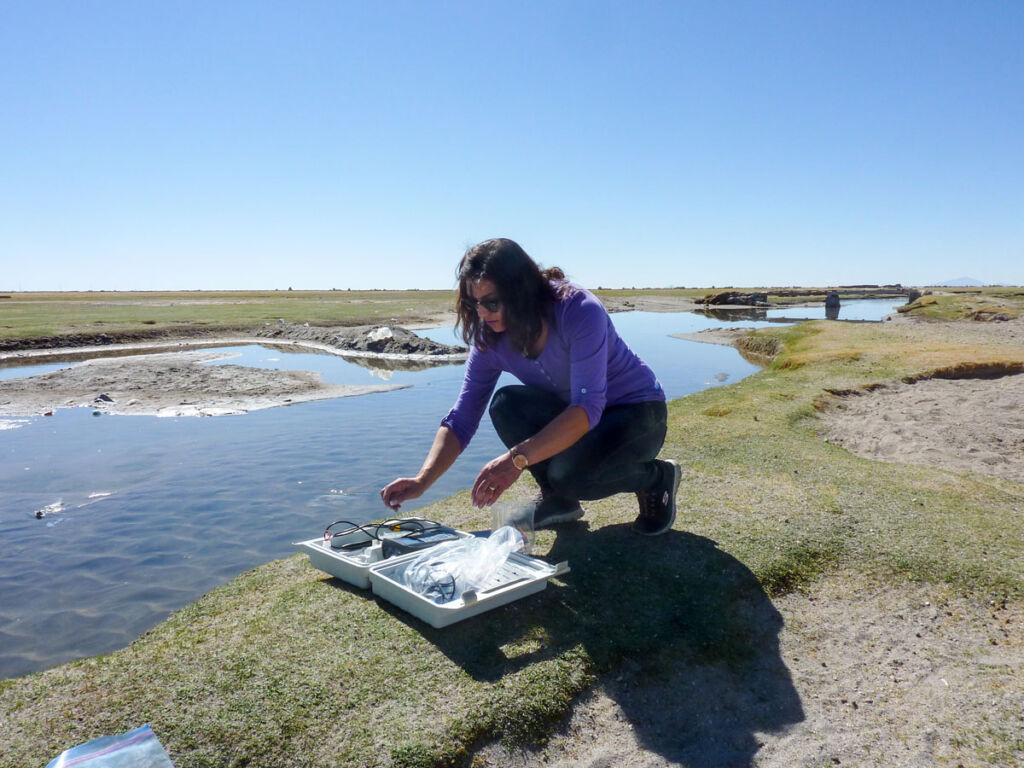

"Local populations obtain their drinking water from traditional shallow wells or shallow tube wells. Unfortunately, Bolivia does not have any maps showing the chemical quality of its water in terms of arsenic, and residents consume water that sometimes contains worrying levels of this substance," explains the doctor.

What are the consequences for their health? "Chronic arsenic ingestion causes cancer, damages the cardiovascular system, damages the kidneys, and can promote the onset of diabetes," replies Jacques Gardon. Arsenic also causes characteristic lesions on the hands and feet: thickening of the skin, or hyperkeratosis, which is typical of arsenic poisoning and can develop into cancer. Jacques Gardon took a close look at the hands of the Urus people of Lake Poopó. They looked surprisingly normal. "They don't show any of these skin symptoms."

How can we explain the absence of this characteristic symptom despite such high levels of arsenic? "A team of Swedish researchers studied a similar situation in certain villages in northern Argentina and hypothesized that it could be a case of adaptation to the poison," explains the researcher. Over generations, the inhabitants have become increasingly able to eliminate arsenic.

Eliminate arsenic

To test this theory, Jacques Gardon, accompanied by Swedish and Bolivian colleagues, measured the levels of arsenic and arsenic derivatives in the urine of 200 women living in ten villages scattered around Lake Poopó. "We focused on women because men, who often leave the village to look for work elsewhere, are not exposed to arsenic in the same way," explains the doctor.

And researchers did indeed find arsenic in their urine, which came as no surprise. What was surprising, however, was the chemical form of the arsenic identified. "It is important to note that arsenic exists in several distinct forms (see box), one of which is less toxic and easier to eliminate than the others. In the general population, the least toxic chemical form accounts for an average of 60% of the arsenic found in urine, but among Urus women, this proportion reaches 80%, "says Jacques Gardon. This means that their metabolism is particularly effective at eliminating the poison.

Adaptation to poison

To explain this extraordinary efficiency, researchers studied the genome of the inhabitants and identified a mutation in a gene that controls arsenic detoxification. "Normally, this mutation is found in about 20% of the population, but we found it in 80% of the people in this Andean community," explains the researcher. This mutation was probably selected over time, with the Urus becoming increasingly able to eliminate arsenic from generation to generation. "This is the first example of human adaptation to a toxin," enthuses Jacques Gardon.

The researcher's enthusiasm was quickly tempered by the doctor's concerns: "Gaining a better understanding of the relationship between the exposome and the genome is fascinating, but what matters most is promoting access to drinking water for all populations." Filtration, ion exchange, oxidation, dilution... there are many effective techniques for removing arsenic from water. "Arsenic has no color, taste, or smell,so most of these people drink contaminated water without knowing it. It's a real public health problem, and our role is also to remedy it."

Effective detoxification

When we drink water containing dissolved arsenic, it is chemically modified in our liver to facilitate its elimination by the kidneys. This modification involves a process called "methylation," which transforms elemental arsenic into either monomethyl arsenic or dimethyl arsenic. While the first form is poorly eliminated by the body, the second is more easily eliminated and is therefore less associated with severe symptoms. It is precisely this dimethyl arsenic that researchers find in the majority of Urus urine samples. The cause is a mutation in the gene encoding the enzyme involved in this methylation process, called arsenic methyltransferase, which promotes the conversion to dimethyl arsenic and explains the effectiveness of the arsenic detoxification process in the Urus.

Find UM podcasts now available on your favorite platform (Spotify, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, etc.).