In bacteria, these prey become predators... of their predators.

When you hear the word "predation," you probably think of a lion chasing a gazelle or a lynx pouncing on a hare in the snow. But did you know that some bacteria also kill and feed on their prey? In an article published today in the scientific journal Plos Biology, we explain how we observed that, in bacteria, prey can become predators... of their predators, as if the gazelle began hunting the lion.

Marie Vasse, University of Montpellier

The world as we know it is home to a multitude of other worlds that are less easily accessible, particularly because they are invisible to the naked eye. I am interested in these microscopic worlds and the organisms that inhabit them. I study how these microorganisms interact, how they cooperate to access resources, for example, how they fight, how they communicate, and even how they kill and eat each other. Between 2019 and 2021 at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH), my colleagues and I conducted a laboratory project to evolve communities of bacteria and try to understand how their interactions change over generations.

Strange results...

In 2021, after conducting one of the project's experiments twice, I left ETH to join CNRS and left it to one of my colleagues to repeat the experiment in question twice more. When conducting research, one way to validate observations is to repeat an experiment to ensure that the results do not change between repetitions. Except that this time, the results were not just slightly different, they were completely reversed!

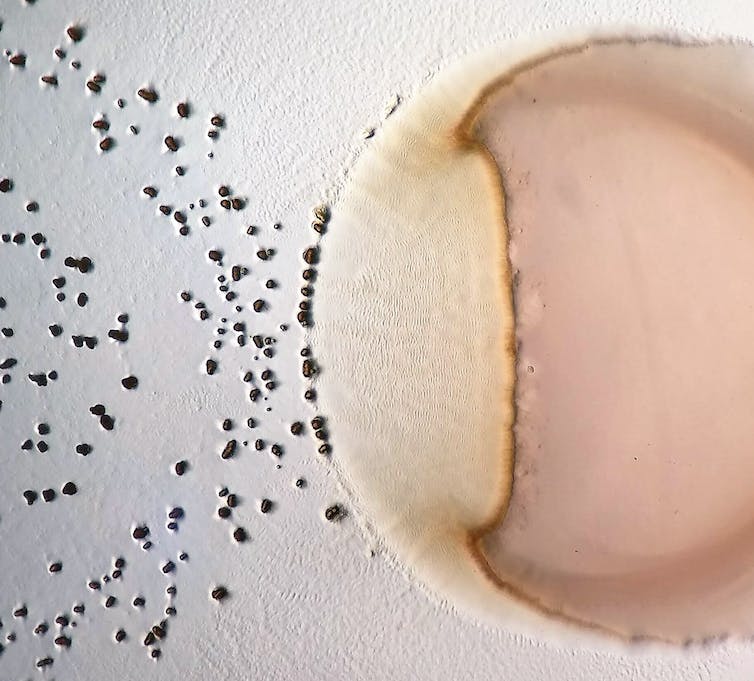

The experiment consisted of placing a bacterium described as a predator and a bacterium described as prey in the same environment to estimate the effectiveness of predation. During the first two repetitions, as well as in previous experiments we had conducted with these two bacterial species, Myxococcus xanthus killed and fed on Pseudomonas fluorescens. It was therefore clear that M. xanthus was the predator and P. fluorescens the prey. During the third repetition, my colleague observed not only that P. fluorescens was expanding rapidly, but also that M. xanthus had completely disappeared from the plastic boxes (called Petri dishes, which contain the culture media) in which we were conducting the experiments.

After much questioning and lengthy discussions, we realized that the difference between her approach to the experiment and mine was that she left the boxes in which P. fluorescens was growing on the laboratory bench, and therefore at room temperature, instead of incubating them at 32°C like M. xanthus, due to lack of space in the incubator. It is important to note that the two species do not grow at the same rate and that, before studying their interactions, they must therefore be grown independently.

We were really surprised and eager to find out more. So we formulated a new research question: can the temperature at which these bacteria grow determine who is the prey and who is the predator? We began by verifying that temperature was indeed the determining factor by growing P. fluorescens at 22°C and 32°C, then placing it in contact with the other species at 32°C, and estimating the number of M. xanthus present after interaction.

The former prey kills and feeds on its predator!

When P. fluorescens was grown at 32°C, we found several million M. xanthus in the boxes; but when it was grown at 22°C, we could not detect any living cells of this species! These results under controlled temperature conditions corroborated our previous observations: the "prey" could exterminate its "predator." It should be noted, however, that to be a predator, it is not enough to kill; one must also be able to feed on one's prey. Since it is difficult to observe a bacterium eating its lunch, we evaluated the microbe's ability to eat another by measuring the effects of the interaction on population size: if P. fluorescens kills and feeds on M. xanthus, we would expect to see fewer living M. xanthus and more P. fluorescens, as the latter would have been able to reproduce thanks to the nutrients obtained from predation.

We therefore conducted a new experiment in which we grew P. fluorescens at 22°C and 32°C and then added either M. xanthus in saline solution or saline solution alone. At 32°C, the presence of M. xanthus greatly reduced the number of P. fluorescens by eating these bacteria. At 22°C, however, M. xanthus was exterminated by P. fluorescens, and on average twice as many P. fluorescens were found than in the presence of saline solution alone: the predator-prey relationship was reversed, and the former prey killed and fed on its predator!

We then tried to understand how P. fluorescens became the predator. By growing this species in a liquid medium, we understood that at 22°C, but not at 32°C, it produced one (or more) molecules and secreted them into the environment. It is this secreted molecule that exterminates M. xanthus.

In our study, P. fluorescens produces the molecule that aids predation even before interacting with the other bacterium. It is therefore certain that at 22°C, P. fluorescens uses this molecule for purposes unknown to us and that this molecule has the side effect of killing M. xanthus.

Finally, we wanted to know whether this molecule could kill other bacteria or whether it was specific. We therefore exposed seven other bacterial species to the secretions of P. fluorescens that had grown at 22°C. No other bacterial species was completely wiped out like M. xanthus, but in the presence of P. fluorescens secretions, the number of Bacillus bataviensis was reduced by an average of 10% and that of Micrococcus luteus by 50%. M. xanthus is therefore not the only bacterium that can be killed by P. fluorescens when grown at 22°C.

We do not yet know exactly what it is about this P. fluorescens molecule that enables it to prey on M. xanthus. Further experiments will be needed to find out, and these are currently underway. However, our study shows that, unlike lions and gazelles (who has ever seen a gazelle devour a lion?), changing a single parameter in the bacteria's growth conditions can have radical consequences on their roles in interactions. If bacteria that have never been described as predators can eradicate their predators simply by growing in a slightly colder environment, it is highly likely that many prey-predator interactions between bacteria are escaping our attention. Another consequence of this study is that it is difficult to categorize bacteria as prey or predators. On the contrary, it is by studying their interactions that we can learn more about how these fascinating microscopic worlds work!

Marie Vasse, Researcher in evolutionary biology, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.