How can industrial wastelands be cleaned up when residents are skeptical?

Nearly eight out of ten French people live near a polluted brownfield site. Despite decontamination operations, redevelopment policies, and the zero net artificialization (ZAN) objective, several thousand sites remain abandoned. Between technical uncertainties, hidden decontamination costs, and collective memory, it remains difficult to restore residents' confidence.

Cecile Bazart, University of Montpellier and Marjorie Tendero, ESSCA School of Management

You may be living, without knowing it, near a polluted brownfield site: this is the case for nearly eight out of ten French people. Despite the redevelopment policies implemented in recent years, particularly as part of France Relance (2020-2022) and the measures put in place by the French Environment and Energy Management Agency (ADEME), these brownfield sites still exist. According to data from the Cartofriches national inventory, more than 9,000 brownfield sites are still awaiting redevelopment projects in France in 2026.

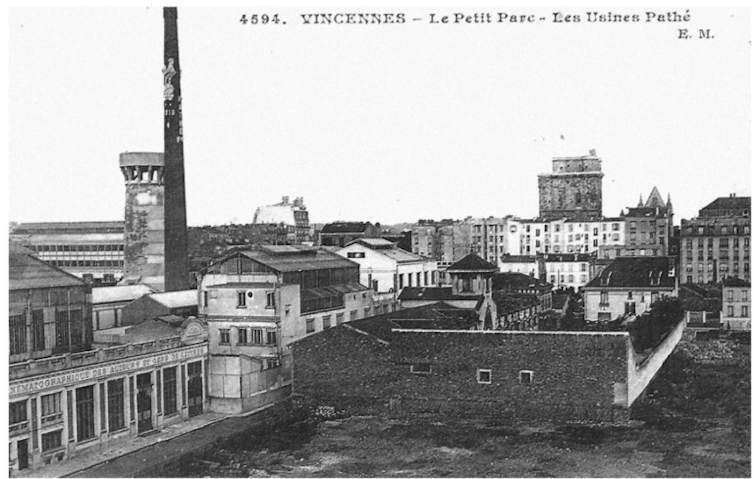

Old factories, landfills, military barracks, port or railway areas, but also hospitals, schools, or service facilities... Brownfield sites are, by nature, very diverse. Most of them are a legacy of our industrial past. But some relate to current service activities that have been set up on former industrial sites that are already contaminated, as illustrated by the former Kodak site in Vincennes (Val-de-Marne).

Beyond their physical impact, certain brownfield sites have left a lasting mark on the land and on collective memory. Some names are now associated with persistent pollution or even social crises, such as Métaleurop, Péchiney, Florange, and AZF.

These abandoned sites, whether built or not, but requiring work before they can be reused, are undergoing various transformations: housing, gardens, offices, shopping centers, or cultural spaces, such as the Belle-de-Mai brownfield site in the 3rd arrondissement of Marseille. At a time when France has committed to the goal of zero net land take (ZAN), the conversion of brownfield sites is a major challenge for local authorities in order to limit urban sprawl and promote the attractiveness of their territories.

However, despite decontamination efforts, many are struggling to find a new use for the land. Why? Because decontaminating the soil is not enough to erase the past or restore the confidence of local residents.

Decontamination: an essential but complex step

Before being redeveloped, a polluted brownfield site undergoes soil testing, which usually results in the development of a management plan. This document defines the measures necessary to make the site compatible with its intended use: excavation of polluted soil, confinement under slabs or asphalt, water management, monitoring over time, or even restrictions on use.

Its content depends on future use. Converting a brownfield site into a logistics warehouse does not involve the same requirements as creating a school. The more "sensitive" the use, the higher the health requirements. In France, therefore, decontamination does not aim to return the soil to a completely pollution-free state. It is based on a trade-off between residual pollution, potential exposure, and future uses.

Added to this is an often underestimated reality: the cost of remediation varies greatly and is rarely known precisely from the outset.

Depending on the characteristics of the site, the pollutants, their depth, and the intended uses, costs can become exponential. In the event of unexpected discoveries (asbestos hidden in fill or higher than expected concentrations of heavy metals), the management plan is modified. In other words, decontamination is often simple on paper, but much more uncertain in reality, with potentially hidden costs.

Stigma, the blind spot of retraining

This technical uncertainty has an impact on residents' perceptions, who sometimes see traces of a past that they thought had been overcome resurfacing as the work progresses. Even after work has been carried out in accordance with standards, many brownfield sites struggle to attract residents, users, or investors.

This is known asthe"stigma effect." A site remains associated with its past, with widely publicized pollution or health and social crises that have left a lasting impression.

In other words, the past continues to be part of the present. The soil has been cleaned up, but the collective memory has not. To continue the metaphor, the wasteland becomes an imperfect present: legally rehabilitated, but symbolically suspect. This stigma has concrete effects: prolonged vacancy or underuse and local opposition, for example.

To objectively assess this mistrust, we conducted a survey of 803 residents living near a polluted brownfield site, spread across 503 French municipalities. The results are clear: nearly 80% of those surveyed said they were dissatisfied with the way polluted brownfield sites are managed and redeveloped in France.

This dissatisfaction is stronger among people who perceive the soil as heavily contaminated, who have already been confronted with pollution situations, or who express low confidence in government actions. They also say they are more reluctant to use or invest in the sites once they have been rehabilitated.

A gap between technical management and perceptions

These results reveal a discrepancy between the technical management of brownfield sites and how they are perceived by residents. From a regulatory standpoint, a site may be declared compatible with its intended use, but from a social standpoint, it may still be perceived as risky.

Several mechanisms explain this discrepancy.

- The first relates to the invisibility of soil pollution. Unlike a dilapidated building, decontaminated soil cannot be seen, which can fuel doubt.

- Collective memory also plays a central role. Polluted brownfields are often associated with a heavy industrial past, sometimes marked by health scandals or social crises that leave lasting traces in people's minds.

- Finally, a lack of information can reinforce suspicion. The concepts of residual pollution or management plans can be difficult for non-specialists to understand. However, when pollution is not completely eliminated, the message can be misunderstood and perceived as a hidden danger.

So even if the technical solutions are sound, the stigma persists. However, without public confidence, there can be no sustainable conversion.

These results highlight a key point: the redevelopment of polluted brownfield sites does not depend solely on the quality of the decontamination work. It depends just as much on the ability to build trust. This requires clear, transparent, and accessible information explaining not only what has been done, but also what remains in place and why. It involves involving local residents in projects at an early stage so that they are not surprised by the changes once decisions have been made. Finally, it requires acknowledging the weight of the past and local memory, rather than seeking to erase it.

In a context of zero net land take (ZAN), polluted brownfield sites represent a land opportunity. However, without taking social and symbolic dimensions into account, technical solutions, however effective they may be, are likely to remain insufficient. Decontaminating the soil is essential. Restoring or building trust among residents is equally important.

Cecile Bazart, Senior Lecturer, University of Montpellier and Marjorie Tendero, Associate Professor in Economics, ESSCA School of Management

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.