How the Omicron BA.2 variant pushed the initial limits of Covid-19

Although the Covid epidemic has taken a back seat in the news, it is by no means over. SARS-CoV-2 continues to circulate and evolve rapidly. Researchers at the "Infectious Diseases and Vectors: Ecology, Genetics, Evolution and Control" unit (University of Montpellier, CNRS, IRD), Mircea Sofonea, associate professor, and Samuel Alizon, director of research, specialists in the epidemiology and evolution of infectious diseases, take stock of Omicron now that it has conquered the world. How can we explain its sub-variants, what do we now know about its capabilities and the effectiveness of our immune system against future variants?

Samuel Alizon, Research Institute for Development (IRD) and Mircea T. Sofonea, University of Montpellier

The Conversation: What is the current situation regarding the circulation of SARS-CoV-2 variants in France and more generally?

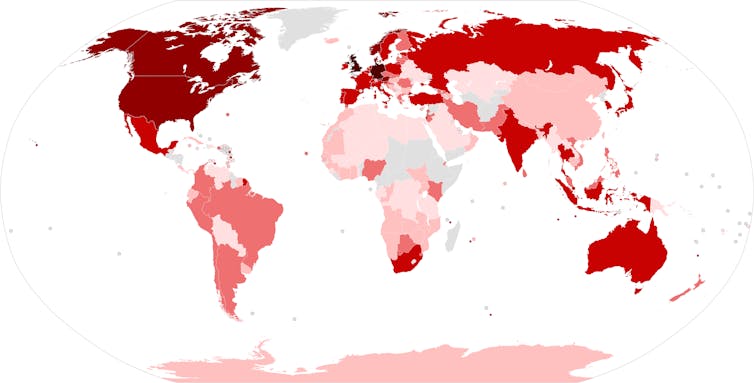

Samuel Alizon: Since December 2021, the Omicron variant, and more specifically the BA.1 lineage (or 21K, in the Nextstrain classification), has replaced the Delta variant (lineage B.1.640) worldwide. This replacement has happened even more quickly than that of the Alpha variant by Delta in 2021. In France and elsewhere, its BA.1.1 sublineage has also been spreading since January.

Even more unexpectedly, in certain countries such as Denmark, South Africa, and India, a cousin lineage known as BA.2 has rapidly become the dominant strain. While the divergence of BA.1.1 from BA.1 is recent (around October 2021), the common ancestor of BA.1 and BA.2 is thought to date back to March 2021. In summary, these two lineages have a common origin (they share more than 30 mutations) but are already almost as divergent as Delta was from Alpha (by more than 35 mutations).

In France, thanks to collaboration with the CERBA laboratory and Montpellier University Hospital, our team estimated that the Omicron/BA.1 variant had become dominant during thethird week of December and hegemonic shortly thereafter. Since the end of January, the percentage of BA.2 among screenings doubled every ten days in January, becoming dominant by the end of February.

newsnodes.com/omicron_tracker/Questzest, CC BY-SA

T.C.: Beyond BA.1 and BA.2, there is talk of a third branch in the Omicron group: BA.3. What is the situation with this?

Mircea T. Sofonea: The Omicron BA.3 sublineage has been known since November 18, 2021, when it was first sequenced in South Africa, less than a month after BA.1 was detected in Botswana. It has 34 mutations on its spike protein (which is also shortened by six amino acids) compared to the initial SARS-CoV-2 reference strain (Wuhan-Hu-1), a number that falls between the BA.1 (39) and BA.2 (31) sublineages, to which it has only one unique mutation.

Based on these arguments, some authors suggest that BA.3 originated from a recombination between BA.1 and BA.2.

Although it is present in at least twenty countries (in southern Africa, Europe, and the United States) and appears (based on in silico approaches) to have a mutational profile that makes it more transmissible than BA.1, it remains extremely rare. Only 543 BA.3 sequences had been deposited in the GISAID database as of March 5, 2022, representing less than 0.05% of global Omicron sequences. In France, 17 BA.3 sequences had been reported as of February 28, 2022, most of which belonged to the same cluster.

This low spread makes it impossible at this stage to accurately quantify its transmission advantage or virulence differential, but it is an optimistic sign regarding the risk that this sublineage poses in the short term. This excludes its classification as a variant in its own right.

T.C.: The fact remains that this "Omicron group" is highly diverse... More so than previous variants? Can we assume that there are in fact several Omicron variants?

M.T.S.: For the moment, the World Health Organization (WHO) designation "Omicron variant" refers to all BA.1, BA.1.1, BA.2, and BA.3 lineages... But it is important to highlight the differences not only between the Omicron group and other variants, but also between BA.1 and BA.2, which are significant from a virological and epidemiological point of view.

Contrary to the fantastical intuition of a linear viral evolution, it should be remembered that the Omicron group did not originate from the Delta variant but likely emerged at the same time: either in the early months of 2020, as a result ofchronic infection in an immunocompromised host, or through retrozoonosis from a murine reservoir.

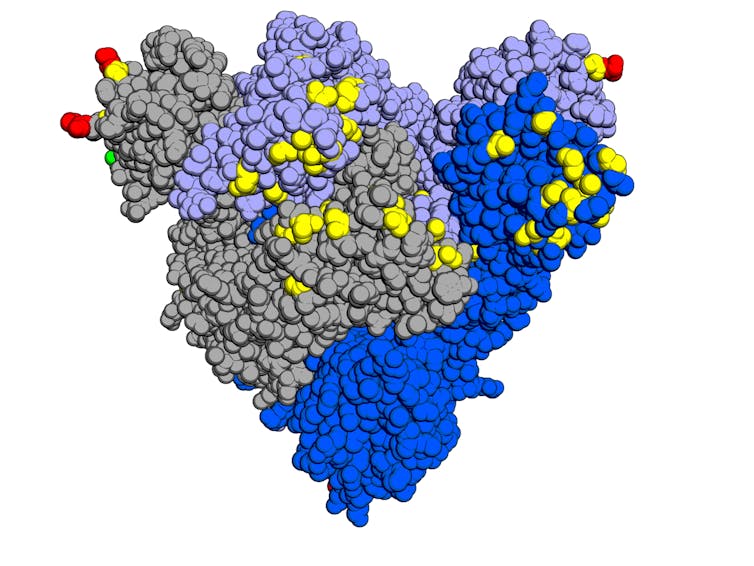

These two hypotheses would indeed explain the significant accumulation of mutations in this group at the time of its detection: at least 31 on its Spike protein alone, more than double that of the Delta variant.

Structural and functional studies of the Omicron spike protein (using high-resolution cryo-electron microscopes, which France sorely lacks) have revealed the numerous (synergistic) consequences of these mutations on its virology, pathogenicity, and epidemiology.

Opabinia regalis, according to Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein, in Cell, CC BY-SA

T.C.: Now that we have a little more perspective, what insights can we gain from studying these changes?

M.T.S.: Many of Omicron's capabilities have indeed been identified or clarified:

● Increased affinity for the human cell receptor ACE2 but reduced membrane fusion capacity,

● Utilization of a second pathway for entry into cells via endocytosis (independent of an enzyme required forentry of other variants),

● Increased replication potential in the epithelium (tissue composed of closely packed cells) of the upper airways (mouth, nose, throat, etc.) and decreased replication potential in the epithelium of the lower airways (lungs, etc.).

● Cross-contamination delay (serial interval) shortened from 4.1 (Delta) to 3.7 days,

● Immune escape, leading to a significant reduction in neutralization by antibodies of post-infectious, vaccine, or therapeutic origin (monoclonal antibodies).

The combination of these properties gives Omicron a transmissibility that is two to three times higher and a lethality that is approximately 70% lower than the Delta variant.

However, it should be noted that this decrease in virulence is not consistent across all age groups: British colleagues have shown that the risk of hospitalization due to Omicron infection is equivalent to that of Delta in children under 10, but four times lower in people aged 60-69.

T.C.: What about vaccination with Omicron?

M.T.S.: According to the latest UK public summary, vaccine efficacy against symptomatic Omicron infection is low and declining rapidly. With only two doses, protection is only 10% after six months, compared to more than 40% for Delta. However, it remains above 40% for up to six months after thethird dose. Fortunately, vaccine efficacy against hospitalization exceeds 75% for up to six months after the booster.

Based on current knowledge, these estimates are equivalent between the two main sub-lineages of Omicron, BA.1 and BA.2, which have comparable severity. The two notable differences between them are a relative transmission advantage of 40% for BA.2 —linked to faster replication in the nasopharynx and an even shorter serial interval (3.3 days)—and an absence of neutralization detectable by the only monoclonal antibodies still active on BA.1, namely sotrovimab and the tixagevimab/cilgavimab combination therapy.

T.C.: Are we still well protected against new strains?

M.T.S.: Between post-infectious immunity and vaccine immunity, less than one-tenth of the French population is now immunologically "naive" to the Covid-19 virus.

The Omicron BA.1 wave conferred cross-immunity to BA.2, with reinfections being rare. However, this immunity is partly temporary, as we have seen with the vaccine.

Since SARS-CoV-2 cannot be eradicated (high contagiousness, imperfect and declining immunity, animal reservoirs), new variants will emerge, selected in particular for their ability to circumvent the immune response. The timing of their appearance and their antigenic properties are currently unpredictable.

Vaccination renewal, if possible with updated or more robust forms, will always be relevant, at least for vulnerable individuals. In addition, work should already be underway to optimize the schedule for future vaccination campaigns and the criteria for temporary and localized reinstatement of protective measures in the event of a resurgence of the epidemic.

T.C.: You mention that new variants will continue to emerge. Is it possible for different variants to coexist?

S.A.: That will depend greatly on cross-immunity. According to population dynamics theory, in the simplest situations, two species cannot coexist if they exploit the same "ecological niche." The Omicron variants seem to be marking a turning point with the colonization of a new "niche" in the upper respiratory tract.

From an immunological perspective, this coexistence could be facilitated by the fact that immunity generated following infection with Delta or vaccination extends little to the upper respiratory tract, which is poorly supplied by the immune system. Furthermore, initial results suggest that natural immunity following Omicron infection provides little protection against other variants.

Finally, we need to specify the scale at which we are talking about coexistence. We know that two variants can coexist within the same person, as demonstrated by the existence of a recombinant virus between the Alpha variant and other lineages, or recent co-infections with Omicron and Delta in the United Kingdom.

On the other hand, since the beginning of the epidemic, we have seen certain variants remain predominant in only a few countries. Here again, scientific ecology teaches us that geographical constraints facilitate the coexistence of species.

T.C.: Does the emergence of Omicron and BA.2, which are overwhelming all other variants, mark a "slowdown" in the epidemic in terms of its ability to diversify?

S.A.: From the point of view of viral evolution, it's quite the opposite. It's impressive to see that BA.2 differs from the Wuhan SARS-CoV-2 sequence by nearly 80 mutations, whereas BA.1 has 70 and Delta "only" 50.

The more a virus circulates, the faster it evolves. And the Omicron variant is circulating extremely quickly... Another example of this massive circulation comes from rare monitoring of animal reservoirs: sequencing data analysis suggests that cryptic lineages appear to be infecting wildlife in New York City's sewers.

The increase in the "biodiversity" of this virus undermines hopes of reaching "evolutionary dead ends," i.e., situations where the mutations necessary for its spread (for example, allowing it to evade the immune system) are so costly that they cannot spread. Indeed, there is a high risk that one of the countless lineages will find a viable solution.

We must also be wary of the long-held belief that viruses become less virulent over time. As demonstrated by this year's discovery of a more virulent-than-average HIV variant that has been circulating since the late 1990s, the opposite is true. While the lethality of infections is decreasing, this primarily reflects improvements in healthcare, vaccines, and treatments.

One of the lessons learned from modeling is that we must be wary of our perceptual biases. During the growth phase of an epidemic, concern increases, and conversely, during the decline phase, we tend to be more optimistic... The challenge for scientists is to stick to the facts. From this perspective, we still lack a great deal of certainty about the Omicron variants. How long does post-infection immunity last and how effective is it? What are the long-term effects of infection? Will we see, as with other variants, cases of long Covid emerging in the coming months?

On all these key issues, we are awaiting the results of research teams abroad, which have far greater resources at their disposal.![]()

Samuel Alizon, Director of Research the CNRS, Research Institute for Development (IRD) and Mircea T. Sofonea, Senior Lecturer in Epidemiology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases, MIVEGEC Laboratory, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.