How are new species of frogs formed?

How do similar animals evolve to the point of forming different species that are unable to interbreed? This question has puzzled evolutionary biologists since Darwin.

Christophe Dufresnes, Nanjing Forestry University and Pierre-André Crochet, University of Montpellier

Some imagine a rapid process, resulting from modifications to a few key genes for mate selection or ecology: hybridization then becomes detrimental, because the offspring, even if viable, will be neither attractive nor adapted to their parents' environments due to their intermediate characteristics.

Others see it rather as the effect of gradual genome differentiation: when populations remain isolated for millions of years, their genes diverge under the effect of mutation and gradually become incompatible, leading to developmental and fertility problems in hybrids.

Hybrid zones as laboratories

To compare these two major hypotheses, we looked at amphibian hybrid zones: geographical regions where genetic lineages of toads, frogs, and tree frogs that are more or less divergent meet and interbreed if they are compatible. The idea is to measure the degree of divergence necessary to limit hybridization and the number of genes potentially responsible for this.

To do this, DNA had to be collected from natural populations, which required considerable fieldwork involving numerous trips across Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, with the help of close colleagues abroad for nearly five years. These samples were then analyzed using tools known as "genomic tools," which provide access to thousands of regions of the genome.

The rewards were considerable: the analyses first led to the discovery of new species and clarified many questions about the evolution of Europeanherpetofauna. In particular, the application of so-called "molecular clocks" to DNA sequences made it possible to date when species appeared, i.e., when they diverged from their cousins. In total, nearly forty natural geographic transitions were compared, representing all known genera on the Old Continent.

Christophe Dufresnes, Provided by the author

It takes time to make a new frog.

The results, published in PNAS, show that it is the entire genome, which has diverged over millions of years, that gradually becomes incompatible between emerging species, rather than just a few key genes. Older lineages therefore have more difficulty hybridizing than younger lineages, as a greater number of genes have lost their compatibility.

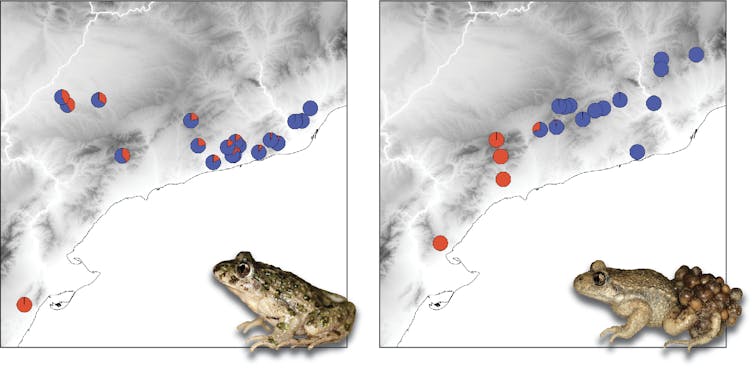

Thus, lineages isolated during the last ice ages are still able to hybridize without difficulty, and traces of this can be found over hundreds of kilometers. This is a sign that their genomes, which are still very similar, have lost none of their compatibility. This can be seen in particular in the Iberian and French forms of the spotted pelodyte, which hybridize throughout Catalonia (see figure).

Christophe Dufresnes, Provided by the author

Several million years later, however, genetic exchange is much more limited. For example, midwife toads and almogavarre toads only interbreed over a few kilometers (see figure). This is because hundreds of genes have become incompatible, and together reduce the viability and fertility of hybrids. Researchers call these "barrier genes" because they are responsible for reproductive barriers.

Christophe Dufresnes, Provided by the author

At first, we make mistakes.

Since they are initially maintained by essentially genetic mechanisms (incompatibilities in numerous genes) that take millions of years to develop, amphibian species evolve relatively slowly. Otherwise, however, they remain identical to our eyes: same ecology, same morphology, same mating calls. These are referred to as "cryptic" species, identifiable only through molecular tools.

But since they still look very similar, these cryptic species always try to hybridize when they encounter each other, which is a mistake. It will take time for sufficiently marked external differences to evolve, so that they can avoid mating with the wrong partner.

Christophe Dufresnes, Provided by the author

A new approach to classifying biodiversity

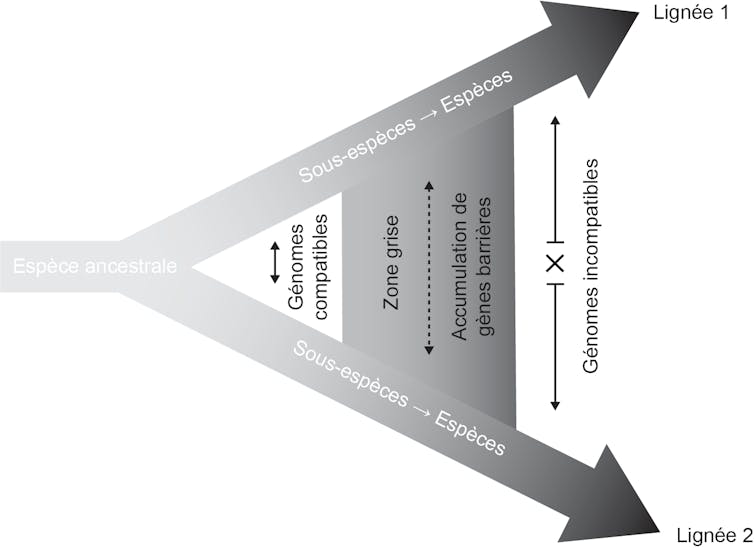

By demonstrating that species formation is a gradual process that can be quantified at the genetic level, the study paves the way for new concepts for categorizing evolutionary lineages into subspecies or species.

More specifically, below two million years of divergence, frogs and toads remain compatible and therefore correspond best to subspecies. It is beyond five million years that we are almost certainly dealing with true species. In between, there is a "gray area" where lineages can nevertheless be classified by inspecting the number of barrier genes already accumulated.

With hundreds of species discovered each year around the world, this type of standardized approach should help establish more objective and therefore more stable taxonomic lists for amphibians, but also for all animal groups, which is necessary for deciding which species to prioritize for protection.![]()

Christophe Dufresnes, University Professor of Zoology, Nanjing Forestry University and Pierre-André Crochet, Director of Research, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.