COVID: A new modeling method to better assess epidemic risks

For thousands of years, humanity has been struck by epidemics... Each time, it has taken protective measures based on the knowledge and opinions of the time regarding modes of contamination. Take, for example, the plagues that ravaged Europe several centuries ago. At the time, it was firmly believed that this devastating disease was caused by the inhalation of miasmas and the resulting imbalance of bodily humors. This led to the proliferation of masks filled with medicinal herbs and fitted with a pointed beak: the classic image of bird-beaked masks...

Simon Mendez, University of Montpellier and Alexandre Nicolas, Claude Bernard University Lyon 1

At the beginning ofthe 20th century, there was a major shift in favor of the predominant role of close contact in transmission. Recommendations changed, and the preventive measures promoted at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic stemmed from this shift: hand washing, possibly with hand sanitizer, disposable tissues, sneezing into your elbow, etc. All of this is to guard against the risk of direct hand-to-hand transmission or transmission via objects contaminated (known as fomites) by an infectious person.

In three years of the pandemic, much has changed in the academic understanding of how respiratory diseases are transmitted. What do we currently know about the mechanisms involved? How can we assess the risks in different situations—between a café terrace, a queue where social distancing is observed, and a busy street? We sought to answer these questions by developing a simple and rapid modeling method.

Shedding light on the aerosol transmission mechanism

At present, there is reason to believe that aerosol transmission is the dominant mechanism of Covid spread.

On this airborne pathway, experimental data collection had begun well before the pandemic: images from Lydia Bourouiba's group on the projection of microdroplets emitted during a sneeze (below), as well as those from Lidia Morawska and William D. Ristenpart's teams, among others, on the size of droplets and aerosols emitted during various expiratory activities, date back several years.

These studies show that coughing and sneezing can project aerosols over distances potentially exceeding 2 m, and that simply talking for one minute can generate as many droplets as a coughing fit.

Despite these results, disagreements persist on basic data such as the distribution of droplet and aerosol sizes produced, which is critical for determining their fall time and likelihood of remaining suspended in the air indoors. Furthermore, experimental difficulties and ethical concerns prevent the study of all possible emission, inhalation, and environmental conditions.

Numerical simulation: the solution?

So how can we increase testing capacity? One answer is to use digital tools, harnessing the computing power of computers.

All that remains is to choose the system to be simulated: airborne transmission occurs through the transport of viruses in droplets and aerosols formed in the respiratory tract (lined with mucus) and the mouth (filled with saliva). the challenge is to simulate the spread of these micro-droplets from the moment they are emitted until they are inhaled—or even until they penetrate and settle in the respiratory tract.

Such fluid dynamics simulations have flourished since the beginning of the pandemic and have highlighted the complexity of the process, the importance of accurately describing the turbulent structures of the flow, the variability of the exhaled air jet depending on phonation, the sensitivity of droplet evaporation to the breath environment, and so on.

If we settle for crude models, the description of risks can be severely affected, and in the early stages of the epidemic, we saw the emergence of numerous studies with questionable assumptions. Conversely, very detailed models, which sophisticatedly simulate the spread of respiratory fluid droplets, offer greater realism... But they are hampered by the complexity of analyzing the data produced (what to do with these ranges of trajectories that vary with every micro-change?) and by their computational time costs—the crux of the matter for numerical simulations.

The "dynamic risk maps" solution

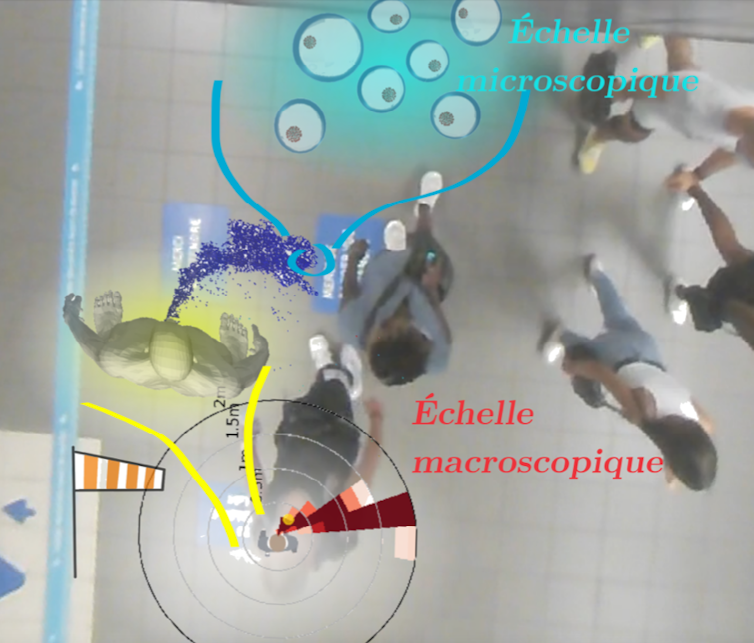

To get the best of both worlds, one idea is to use highly detailed fluid dynamics simulations with millimeter-level resolution and estimate the risk dynamics around an emitter in a more aggregated manner, i.e., without worrying about the precise location of each micro-droplet.

Except that a single map is not enough: in reality, the resulting "risk map" varies depending on whether the person is talking or walking, on the wind or air currents, etc. It is therefore necessary to build up a whole library of reference situations and, in the intervals between them, infer those that are missing. That is what we set out to do.

The results are clear and straightforward. It appears that even the slightest breeze drastically reduces the risk of viral transmission. This puts an end to a debate that began at the start of the pandemic, when people wondered whether wind might actually promote infection by carrying droplets and aerosols further. In fact, in all the scenarios studied, wind disperses them.

More generally, the significant reduction in digital costs thanks to the use of "dynamic risk maps" has made it possible to study concrete situations involving dozens or even hundreds of people.

Tangible results

In practical terms, we were able to walk the streets of Lyon in the midst of the pandemic and set up our camera equipment (filming people from above while respecting their anonymity) in various locations, both outdoors and indoors in open spaces (large and well ventilated). These included an SNCF train station, a metro station, busy streets, an open-air market, café terraces, and a landscaped riverbank along the Rhône.

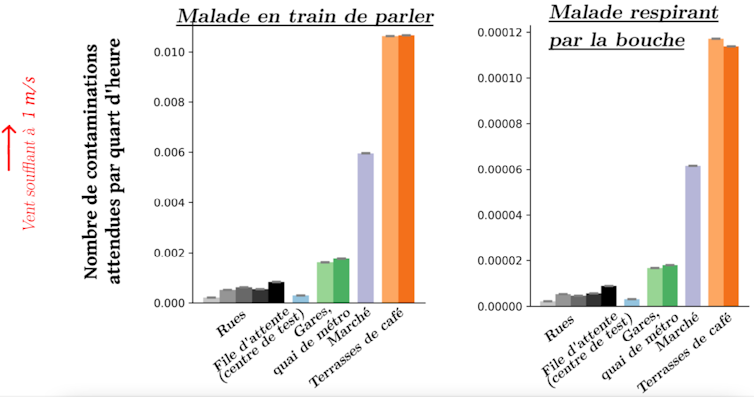

From these videos, we extracted the trajectories and orientations of pedestrians' heads and linked this data to the aforementioned risk maps (Figure 1). Results:

- Busy streets (not crowded) pose a very low risk compared to the open-air market, where there were many more people and they were much closer together. As might be expected, density plays a major role.

- All of these situations presented less risk of new infections than café terraces (Figure 3), where people share close and prolonged contact, even though the overall density is lower.

- Exhalation plays a major role, as the emission of droplets by a person who is speaking is much higher than when they are breathing through their mouth (and, even more so, through their nose).

This prioritization of concrete scenarios based on theoretical-numerical models illustrates how high-fidelity simulations can be used to examine everyday situations. This can serve as a decision-making aid in public health policy.

The modeling tool thus plays a valuable role as a bridge between fundamental knowledge about airborne virus transmission and the health measures to be implemented.

Strengths and limitations of a promising approach

Compared to sophisticated approaches, where the fate of each respiratory droplet is predicted and influenced by numerous phenomena (air recirculation around street furniture, the influence of each pedestrian's wake, etc.), our approach allows us to estimate the risks in real-life situations in just a few minutes, with the most costly simulations having been carried out upstream, once and for all.

Of course, this comes at a price: the impact of pedestrians other than the emitter is not taken into account, which proves limiting in cases of extremely dense crowds. Other effects, such as the influence of temperature on the dispersion of exhaled aerosols, could, however, be incorporated into future improvements.

Despite these limitations, there are many possible uses, as the transmission model can be combined with field measurements for risk prioritization or coupled with simulated pedestrian trajectories. This makes it possible, for example, to quantify in advance the influence of architectural choices on transmission risks in a building or to organize crowd flow during an epidemic.

Simon Mendez, Research Fellow at the CNRS, Mathematics and Modeling Laboratory, University of Montpellier and Alexandre Nicolas, Research Fellow at the CNRS; physicist, Claude Bernard University Lyon 1

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.