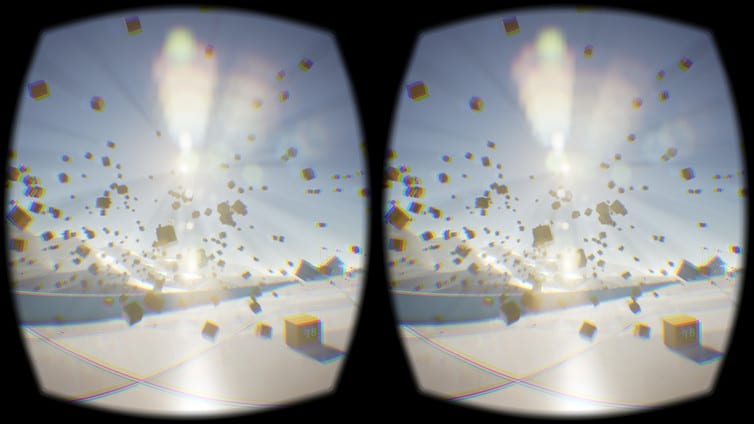

Cyberkinetosis, or virtual reality headset sickness

It's a fact. We experience difficulties when we put a virtual reality (VR) headset on our heads. Discomfort, sweating, drowsiness, migraines, even nausea in cases of prolonged use—we are all pretty much equal in this regard and find this phenomenon unpleasant.

Benoit Bardy, University of Montpellier

At a time when the great leap into the virtual world seems to be gaining momentum and virtual reality headsets are becoming more widely available, this is causing confusion. Let's call this phenomenon cyberkinetosis, in reference to the English term. cybersickness. The motion sickness refers more broadly to motion sickness, or travel sickness, as it occurs when traveling by boat, of course, but also by car, train, and sometimes by plane.

The origins of cyber sickness are partly specific to VR headset technology, and partly common to other situations that cause motion sickness. Among the reasons specific to VR is the still-nascent technology, which introduces a series of inconsistencies. For example, the delay in the sensorimotor loop (between the moment we move our head and the moment the image inside the headset is updated) reaches values of 50 to 200 milliseconds. This produces all kinds of neurophysiological disturbances. For example, the functioning of the vestibulo-ocular reflex which allows you to maintain your line of sight when turning your head.

Mikael Häggström — Image: ThreeNeuronArc.png, CC BY-SA

The interocular distance of the headset, the fixed distance between the eye and the screen, the long image refresh time, the limited resolution, and the rough overlap of the right and left visual fields create numerous distortions, resulting in an incorrect geometry of the spatio-temporal structure of the virtual scene. These inconsistencies are not simply intra-sensory or inter-sensory, they are also sensorimotor, or rather motor-sensory. Indeed, it is our movements that reveal these inconsistencies, triggering an unrealistic, destabilizing action-perception loop that causes motion sickness.

These limitations are significant but not essential. Technology is advancing. The new headsets on the market have already corrected the errors of their predecessors, with new features such as eye tracking, which allows the image to rotate in sync with the eyes. Latency and resolution have improved considerably, providing a realistic sensorimotor loop that limits our nausea reactions.

Conflict between the senses

The second category of reasons is more fundamental: it concerns the relationships between our senses, a topic dear to cognitive science and neuroscience, sometimes referred to as multisensory integration. The classic theory of motion sickness is based on the rarely questioned assumption of a conflict between our senses.

However, the idea that our senses are in conflict, and therefore can deceive us, is not easy to accept. How can we walk, run, grasp the objects around us, play sports, dance, drive our cars, in short, perform hundreds of daily motor acts, sometimes with extreme precision, in an often changing physical environment, in a car or on a train for example, while having to be wary of these sensory flows that we ourselves have created and that are supposed to help us move around efficiently? Something doesn't add up.

Are we sick when we drive our car calmly on the highway? When we take the elevator? When we walk on a treadmill or on the beach against the wind? As a very general rule, the answer is no.

Clicsouris/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

However, walking on a treadmill, for example, means that the optical flow at eye level is not only the result of the horizontal forces generated to move forward, but also of the speed of the treadmill; the visual feedback is therefore at odds with the proprioceptive and vestibular feedback. Basically, our eyes give us the impression that we are moving twice as fast as our feet! And half as fast when we walk on the beach against the wind.

These examples suggest that the non-redundancy between our senses is not abnormal: we could even say that it is more the rule than the exception, that any physical situation introduces multiple covariations (rather than conflicts) between our perceptual modalities. In fact, the subtle division of labor between our senses, with different detection thresholds, sensitive to complementary physical quantities, is precisely there to cover all possible situations we may encounter and, with rare exceptions, to inform us accurately about the reality of our interaction with the world.

Our movements are relative

Advocates of an explanation for motion sickness based on conflict theory often forget the physics of the world we live in! It is possible to be simultaneously moving vertically relative to the earth and stationary relative to the visual world. This visuo-proprioceptive configuration reveals that we are, for example, in an elevator. The reason for this is, of course, that our movements are relative, that they depend on the frame of reference (terrestrial, gravitational, inertial) in which they are observed, and that it is quite common to be stationary relative to one frame of reference and moving relative to another at the same time. Our senses, in their complementarity, are very good at detecting these relative persistencies and changes.

So why do we feel sick? Because these situations are unusual, they require new sensory covariations, and the sensory-motor couplings involved in this new relationship need to be built, which requires slow adaptation.

Acquiring the sea legs that allow you to become a true sea dog follows this path. On the deck of a boat, we must learn to control our balance based on these new sensory relationships, anticipate the movements of the deck and the disruptive effects of the swell, and build this new sensorimotor loop that is better suited to the moving surface. This process takes time, causes great destabilization, and it is this loss of stability that creates motion sickness.

A new postural theory of motion sickness has gradually developed over the last 25 years, attributing the causes of motion sickness to the loss of stability in the sensorimotor loop. This theory predicts the onset of postural instability before that of motion sickness. In fact, it is not, or not only, because we are sick that we are unstable; it is also and above all because we are unstable that we are sick. This theory simply explains why women are often more sensitive than men, due to a different distribution of body mass, or children more than adults, due to their growth, which continuously changes their balance.

This theory simply explains why we are more often sick in a car as a passenger than as a driver (the sensorimotor loop is absent in the first case, but not in the second), and why staring at the horizon on the deck of a boat helps to reduce seasickness. The horizon is in fact a stationary singularity in the optical flow, providing a reference point that helps stabilize our postural oscillations.

Check your posture

Applied to VR headset use, a postural theory of cyberkinetosis is currently being developed, based on experimental data and the subjective experiences of gamers and VR software manufacturers. Technological tricks—a virtual nose between the two hemifields, a fixed reference point providing a landmark—as well as scenarios that limit jerky movements of the head and eyes and promote situations of active posture control, appear intuitively. These tricks and scenarios, combined with the rapid evolution of technical specifications for headsets, improve motor control and thus reduce cyberkinetosis.

A multisensory simulator unique in France—iMose—was recently installed at the EuroMov center in Montpellier.

![]() Thanks to its extraordinary dimensions (an RV gondola at the end of a 7-meter-high robotic arm) and its six degrees of freedom, it can artificially create and manipulate all kinds of sensory relationships. Research programs on cyberkinetosis are underway, but also more broadly on multisensory control of movement, loss of orientation in pilots, the dynamics of adaptation to these unusual situations, individual and cultural differences, and the role that virtual reality can play in learning and rehabilitation. This technology platform is open to researchers and manufacturers in the sector who wish to explore these scientific questions and test their virtual reality equipment.

Thanks to its extraordinary dimensions (an RV gondola at the end of a 7-meter-high robotic arm) and its six degrees of freedom, it can artificially create and manipulate all kinds of sensory relationships. Research programs on cyberkinetosis are underway, but also more broadly on multisensory control of movement, loss of orientation in pilots, the dynamics of adaptation to these unusual situations, individual and cultural differences, and the role that virtual reality can play in learning and rehabilitation. This technology platform is open to researchers and manufacturers in the sector who wish to explore these scientific questions and test their virtual reality equipment.

Benoit BardyProfessor of Movement Sciences, Director of the EuroMov Center, Senior Member of the Institut Universitaire de France (IUF), University of Montpellier

The original version of this article was published on The Conversation.