From Facebook to plant development: when networks get involved

Telephone network, social network, road network, professional network... The term "network" has now entered everyday language. An IT network consisting of interconnected computers, or a subway network whose stations are connected by lines, are two intuitive representations of this concept.

Jeremy Lavarenne, Research Institute for Development (IRD)

Quinn Dombrowski/Flickr, CC BY-SA

The graph theory, transposed into the real world through network theory, teaches us that networks have intrinsic mathematical properties. These properties make it possible to study them formally, thereby enabling us to better understand and even anticipate how the systems described by networks function.

What is a network?

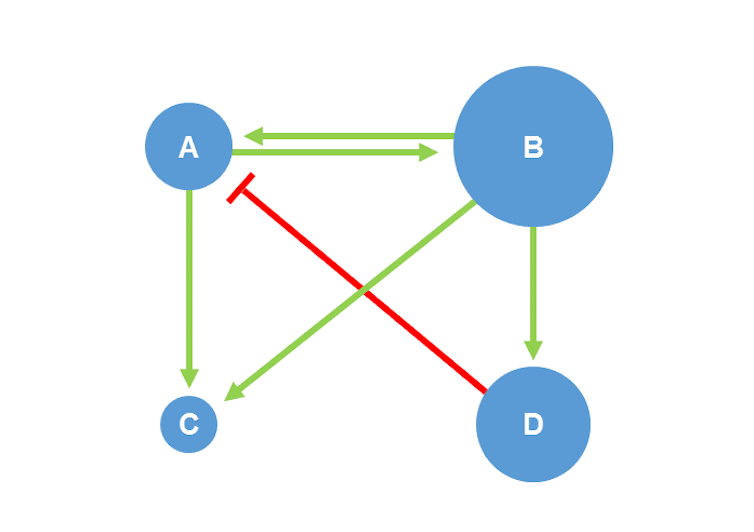

The Wiktionary defines a network as a "set of objects or people connected or linked together," but also as "the set of relationships thus established." There are several ways to represent a network, the most common and intuitive of which is in the form of a mathematical object called a graph. This is defined as a set of nodes and edges interconnecting these nodes. It can include an overlay of information, such as adding a weight value to nodes to represent the relative importance of an object, or the directionality of edges to distinguish the direction of the relationship between two objects. For example, on the Twitter microblogging network, the connection between a follower and the account being followed is not necessarily reciprocal: the interaction is directed and can be represented by an arrow pointing from the follower to the account being followed.

The internet, ecosystems, the human brain, economic organizations... Graphs can be used to represent—or "model"—and analyze a wide variety of complex systems. This makes these approaches all the more interesting, as complex systems are defined by behavior that is difficult to understand and anticipate based solely on individual knowledge of their components.

Network analysis: a wide range of applications

Coupled with ever-improving computing power, advances in graph theory and algorithmics provide us with a set of tools that enable us to extract information from large networks. It is common to encounter graphs composed of thousands of nodes and tens of thousands of edges, whose information may seem difficult to grasp at first glance.

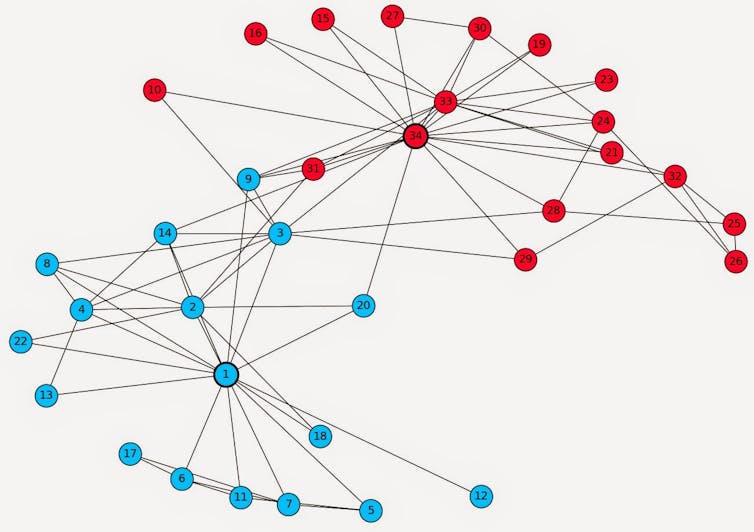

A well-known and amusing example that helps us understand the value of network analysis comes from the social sciences. Created by Wayne W. Zachary between 1970 and 1972, Zachary's Karate Club is a graph documenting 78 affinity links between 34 members of a martial arts club. Interested in the role of information and sentiment flows in the splitting of small groups, the author applied an algorithm that grouped members with the most affinities to each other in order to hypothesize about the formation of subgroups that could result from a potential conflict. Interestingly, such an event occurred during the study, causing an actual split in the group, identical to the one predicted by the affinity network analysis, except for one person, and validating Zachary's model to 97%.

Historical DataNinjas Blog

Another example, borrowed from the field of ecology and illustrated in 2016 by Mauro Martino based on research by Guo and colleagues, presents a network composed of different plant species (nodes) sharing at least one species of symbiotic ants (edges). Here, analyzing the network as part of a simulation of the gradual and random disappearance of certain ant species as a result of climate change makes it possible to estimate the network's resilience, i.e., its ability to withstand environmental changes while remaining capable of performing its functions. This approach thus provides an additional indicator to those already in existence for describing the fragility of ecosystems in the face of climate change.

The formation of cereal roots

Climate change is also set to have a significant impact on agricultural activities and yields, due to changes in rainfall patterns leading to more severe weather events. To compensate for these fluctuations, agronomists and biologists agree on the importance of research into the root system, the "hidden half" of plants. This is the first line of defense when the soil is water-deficient (drought) or contaminated with excessive sodium chloride (salinization). Cereals, and in particular the Poaceae family, which includes rice, corn, and wheat, are the direct or indirect source of nearly half of humanity's food calories. In order to adapt plants to these consequences of global climate change, it is therefore strategic to understand, on the one hand, the genetic determinants of root system architecture. These can control, for example, the number or diameter of roots, the angle or depth of rooting. On the other hand, it is important to understand the role of this architecture in making plants tolerant to these stresses.

In this context, my thesis work focuses on understanding the early stages of root development in rice. At first glance, there is no network in sight! However, one branch of network science is closely related to biology: the study of gene regulatory networks.

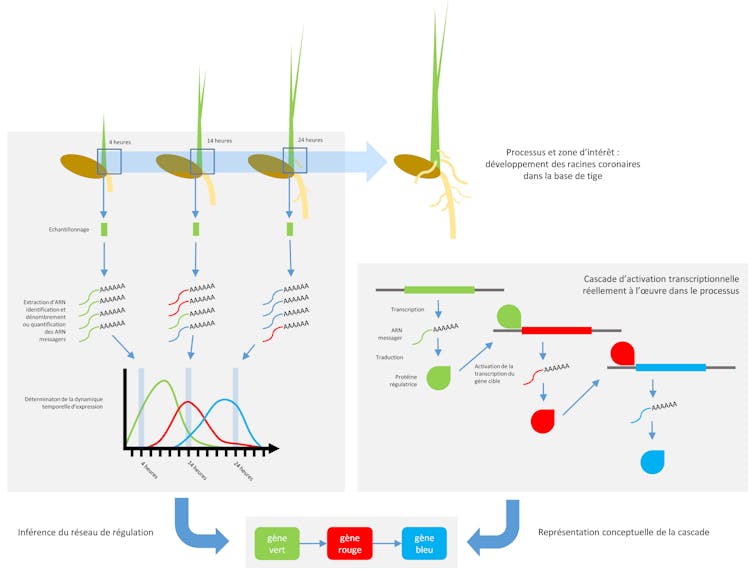

During a developmental process such as rootorganogenesis, specific genes are translated into proteins. Some of these proteins are involved in the regulation of other genes. One way to study a biological process is to identify the links between, on the one hand, the genes encoding regulators and, on the other hand, the genes whose expression they regulate, in order to begin modeling a gene regulatory network.

This is what we did to study and discover new genetic determinants involved in the formation of crown roots, a category of roots that emerge in a crown from the internodes of the stem as the plant develops, and constitute the majority of the root system in cereals.

These crown roots form the majority of the root system in cereals. To this end, and throughout the early stages of crown root formation in rice, we sampled the organ concerned at regular intervals. Thanks to recent advances in transcriptomics techniques, we have identified variations in gene expression levels during the development of a crown root in rice. Using a subset of genes with high variations in expression levels, we predicted which gene regulates which other gene using an algorithm that analyzes similarities and time shifts between gene expression profiles over time. On this basis, we constructed a gene regulation network model that can explain these variations in expression.

What applications?

From a fundamental perspective, the main benefit of analyzing this network is that it allows us to identify new links between genes already known to be involved in root development, as well as genes whose role in this process was previously unknown. Furthermore, analyzing this network using clustering methods (as presented in Zachary's example) makes it possible to identify groups of genes that are more strongly connected to each other than to the rest of the network. Such sets, known as modules, are likely to play a role in a given biological function. Finally, identifying the most connected nodes in the network makes it possible to pinpoint the genes that play a crucial role in the process as a whole.

In this respect, these "systems biology" approaches, which take into account the process as a whole rather than focusing on certain elements, are interesting from a fundamental point of view for formulating new hypotheses about how it works. From an applied perspective, they can be used to detect new target genes for varietal selection, for example in our case to modulate root architecture and obtain plants that are more tolerant to stresses such as drought. Finally, whether in fundamental or applied research, the predictive capabilities of systemic approaches could reduce the time needed to create new plant varieties.

Recent advances in sequencing technologies (such as RNAseq, for "RNA sequencing") and methods for modeling and analyzing gene regulatory networks are opening up their use to an increasingly wide range of crop species. This leads us to believe that varietal selection activities, which until now have been based on the selection of gene variants without consideration of their role in gene regulation, will be enriched in the coming years by systems biology. Breeders could thus incorporate "regulatory network engineering" functions into their work. Varietal crosses and biotechnological tools would then have a role to play in adding or rewiring network nodes that control specific aspects of plant growth or stress response.

![]() To learn more about network science, we recommend reading Albert-László Barabási's book "Network Science," which is available for free on the author's website. We would like to thank Antony Champion (IRD) for proofreading this text..

To learn more about network science, we recommend reading Albert-László Barabási's book "Network Science," which is available for free on the author's website. We would like to thank Antony Champion (IRD) for proofreading this text..

Jeremy LavarenneAgricultural Engineer, CIFRE Doctoral Student, University of Montpellier-Biogemma, Research Institute for Development (IRD)

The original version of this article was published on The Conversation.