Cranial deformation: practiced by the Incas, it is also a universal custom.

Barbarism, torture, savagery—these are the first words that come to mind when skull deformation is mentioned. In 1931, the English anthropologist J. Dingwall reflected: "It is likely that this curious yet widespread custom of artificially deforming the skull is the least understood of all the ethnic mutilations that have been passed down since ancient times."

Jerome Thomas, University of Montpellier

Indeed, they provoke condemnation and horror, disgust and dismay, and carry with them the supposed signs of societies that are less evolved and, above all, exotic, far removed from our European lands.

Alien skulls

Beyond an almost visceral repulsion, deformities also inspire numerous fantasies and excite the imagination. They are said to be proof of the existence of extraterrestrial races with superior intelligence that colonized our planet in distant times.

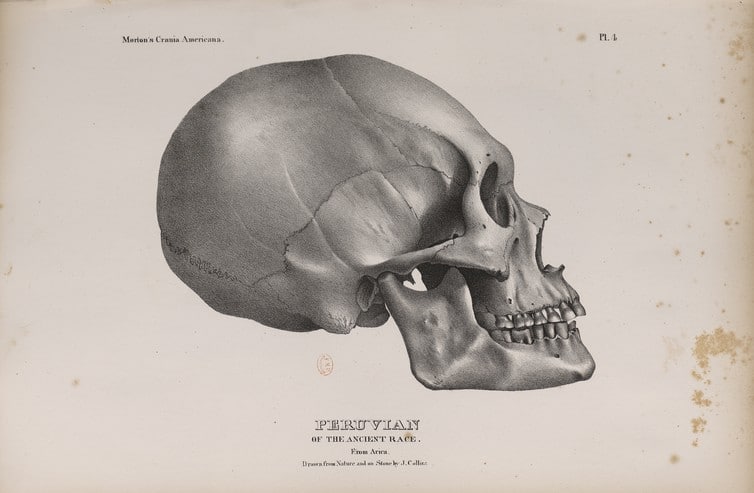

In 2012, a newspaper ran the headline "Alien skeletons?" about the discovery in Mexico of human remains with deformed skulls. In the19th century, anthropologists such as von Tschudi even disputed the artificial nature of cranial deformations.

Far from these clichés and sensationalism, occipital manipulation offers a vast field of study on the relationship to the body in its cultural, social, ethnic, and religious dimensions.

Influencing head growth in order to deliberately change its shape is a widespread custom among humans.

J. Thomas, Author provided

An ancient and universal practice

The artificial deformation of newborn skulls is an ancient universal tradition. From Europe to the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Oceania, no region escaped skull shaping.

The oldest traces of this practice date back to around 45,000 BC in Iraq. However, researchers are still debating whether the skull fragments discovered show signs of deformation.

On the American continent, this custom has accompanied the development of Andean communities since at least the6th millennium BC and has become a widespread practice. Out of a collection of 500 Peruvian skeletons preserved in Paris, only 60 show no signs of deformation. At many sites excavated in Mesoamerica, individuals with deformed skulls account for more than 90% of the cases observed. In Mexico, the oldest deformed skull discovered by archaeologists dates back to 8500-7000 BC

In South America, cranial deformation most likely developed on the Pacific coast around 3500-3000 BC.

National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology, and History of Peru in Lima, Author provided

Some societies made remarkable use of it. The Chinchorro culture (c. 7000 BC to c. 1100 BC), established in the far north of Chile and southern Peru, practiced a very pronounced form of deformation from thethird millennium onwards. Several ethnic groups adopted these customs, the best known of which are the Paracas (600 BC-100 AD), Nazca (200 BC-600 AD) and Tiwanaku (c. 700-c. 1200 AD) cultures around Lake Titicaca.

These practices remained alive in these regions when the Incas dominated much of the Cordillera from the mid-15th century onwards. A number of communities under their rule had long been in the habit of artificially deforming the occiput of infants, following the example of their conquerors.

In 1557, the Italian philosopher Girolamo Cardano listed the regions where these practices were still in use: Cuba, Mexico, Cumana (Venezuela), Porto Velho (Brazil), and Peru. In the 1550s, the clergyman Cieza de León mentioned that north of Cali, Colombia, there lived a people whose heads he described as long and broad, adding that in many regions children had deformed heads, which delighted their parents.

The Spanish were greatly impressed by this custom, which seemed so strange to them. In fact, by the16th century, it was only practiced in exceptional and residual cases in a few regions of Northern Europe.

The Spanish fought fiercely against this practice. They sensed rather than understood the religious dimension of the deformations. At theThird Council of Lima (1585), the religious authorities decided to ban cranial deformations more strictly and to punish them severely: 20 lashes if a person deformed their head. However, the practice continued for a long time.

How did the Incas do it?

Several techniques are used to reshape skulls. They are universal. A child's skull is very malleable, and this flexibility makes it possible to reshape it before its final form is established. The cranial vault is remarkably plastic and well suited to this type of manipulation. It is not until the age of six that definitive ossification occurs. The sutures of the cranial vault allow for a certain amount of mobility between the bones, and external compression forces, such as boards or straps, determine the growth of the sutures, which are directly affected by these forces.

J.T, Author provided

The heads were deformed using several methods, with flattening affecting either the top of the skull or the sides. Three types of deformation devices were used: the cradle, in which deformation was achieved by applying pressure to the head of the newborn, who was laid down and immobilized in a wooden cradle; boards, in which the head was clamped between two pieces of wood placed on the forehead and the back of the neck, thus flattening the skull from front to back. This is known as "tabular" flattening; finally, there are ties or headbands, often called chuco, where the skull is compressed from birth using a very tight bandage. This is the "annular or circular" type. The latter technique is most often described by the Spanish in what was once the Inca Empire.

Deforming skulls to bind the soul to the body

But why did the Incas deform skulls?

Skull shaping allows peoples to be distinguished from one another, indelibly imprints group membership on the body, adorns and embellishes individuals, marks social status, and refers to religion, cosmology, beliefs, and initiation rites.

However, researchers have focused primarily on the cultural, social, and ethnic dimensions of these practices, while the religious dimension is fundamental.

The head represents the center of an individual's spiritual life. It is the seat of vital force and symbolizes the spirit. The animic force, i.e., a beneficial and spiritual power present in the head, is perceived as a beneficial power that gives strength, authority, and vitality to those who possess it and that can be appropriated provided it is controlled. The head can be associated with two main characteristics: it metaphorically represents the cosmos and is the seat of the soul.

In Inca cosmology, there is a bodily opposition: front/back—the Incas associate the front of the body with the past and clarity, and the back with the future and darkness—and an opposition between top and bottom, with the head corresponding to the upper world, that of the ideal body represented by the celestial bodies. Finally, several spiritual principles surround and animate the human body. One of the most important is animu, a term borrowed from the Spanish anima, "soul," which is an "animic force," spiritual and not only human.

The animu is distributed throughout the body but can be concentrated in certain areas and bodily substances: mainly the head, blood, and heart. The animu is a vital force that animates everything, whether human beings, plants, animals, or elements of the landscape. Anim is born in the solar plexus, circulates throughout the body, and exits through the head at death. Holding the child's head tightly at birth therefore becomes an imperative and vital step, as the soul is not yet firmly attached to the newborn's body, which can cause the loss of anim. This is because the fontanelle is not yet closed in infants.

In order to attach the soul to the body, technical measures such as cranial deformation are essential and imperative. Deforming the head hardens and closes the body, solidifies it, and closes at least one of its openings.

J.T, Author provided

Now extinct, even though they were still practiced in the Andes by the Chama, a community established in northeastern Peru in the mid-20th century.e In the 19th century, cranial deformations were evidence of a universal practice found in all social spheres.

![]() If in our contemporary societies, body modification practices are perceived as markers of identity construction and the affirmation of a "sovereign self," this interpretive framework should not be applied to older civilizations, particularly those of the Andes. A key element would be missing in order to understand them: their cosmological and religious dimension. Symbolically, in these societies, the manipulation of the occiput, like any form of body adornment, plays a fundamental role, as it distinguishes, adorns, and protects. It protects against evil foreign influences and defends the body and its most vulnerable parts from spells. Manipulating the head, the most visible and exposed part of the body, is a strong signal. It is an extremely important symbolic language, and the Peruvian populations were no exception.

If in our contemporary societies, body modification practices are perceived as markers of identity construction and the affirmation of a "sovereign self," this interpretive framework should not be applied to older civilizations, particularly those of the Andes. A key element would be missing in order to understand them: their cosmological and religious dimension. Symbolically, in these societies, the manipulation of the occiput, like any form of body adornment, plays a fundamental role, as it distinguishes, adorns, and protects. It protects against evil foreign influences and defends the body and its most vulnerable parts from spells. Manipulating the head, the most visible and exposed part of the body, is a strong signal. It is an extremely important symbolic language, and the Peruvian populations were no exception.

Jerome Thomas, Researcher, University of Montpellier

The original version of this article was published on The Conversation.