Robots increasingly closer to humans

Our society is changing. Increasingly, we are welcoming a new species among us: robots.

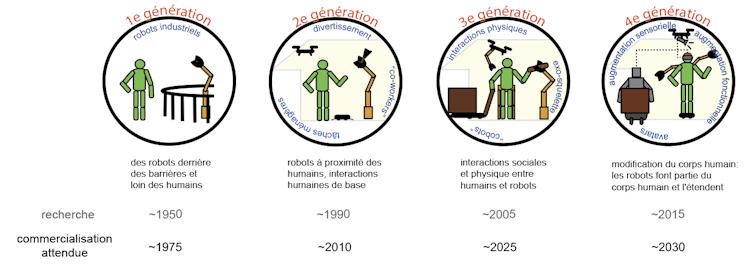

Developing interactions between humans and robots is not only a robotic challenge but also a challenge in understanding humans and human society: how humans perceive robots, communicate with them, behave around them, and accept them (or not). This becomes all the more important with the arrival of the fourth generation of robots, which integrate directly into the human body.

Ganesh Gowrishankar, University of Montpellier

We are working to better understand what is known as the "embodiment" of these devices: as these robots become "one" with us, they change our behavior and our brains.

The first generation of human-robot interactions for industry

This "journey through time" of robots, which have gone from being dangerous machines to an integral part of human society, has been going on for more than forty years.

Robots vary greatly in terms of size (from micrometric or even nanometric on the one hand, to human-sized or larger on the other), how they move, and their functions (industrial, space, defense, for example). Here, I am not focusing on the robots themselves, but on the interactions between humans and robots, which, in my opinion, have developed over four generations.

Large-scale interactions between humans and robots began with the advent of industrial robots, the first of which was introduced by General Motors in 1961. These slowly became widespread, and by the early 1980s, industrial robots were present in the United States, Europe, and Japan.

These industrial robots have enabled us to observe the first generation of human-robot interactions: they generally operate in designated areas to ensure that humans do not come into contact with them, even by mistake.

Industrial robots, which were first popularized by automotive assembly tasks, are now used for a variety of tasks, such as welding, painting, assembly, disassembly, pick and place for printed circuit boards, packaging, and labeling.

Work side by side

Robotics research during this period focused on bringing robots closer to humans, which led to a second generation of human-robot interactions, materializing for the general public in the early 2000s when machines such as Roomba and Aibo began entering our homes.

These second-generation robots work alongside humans in our homes and offices for "service applications," such as cleaning floors, mowing lawns, and cleaning swimming pools—a market worth approximately $13 billion in 2019. In 2009, there were approximately 1.3 million service robots worldwide; a number that had grown to approximately 32 million by 2020.

However, although these robots operate in a more human environment than industrial robots, they still interact in a fairly minimal and basic way. Most of their daily tasks are independent tasks that require little interaction. In fact, they often tryto avoid interactions with humans —which is not always easy.

Interact with humans

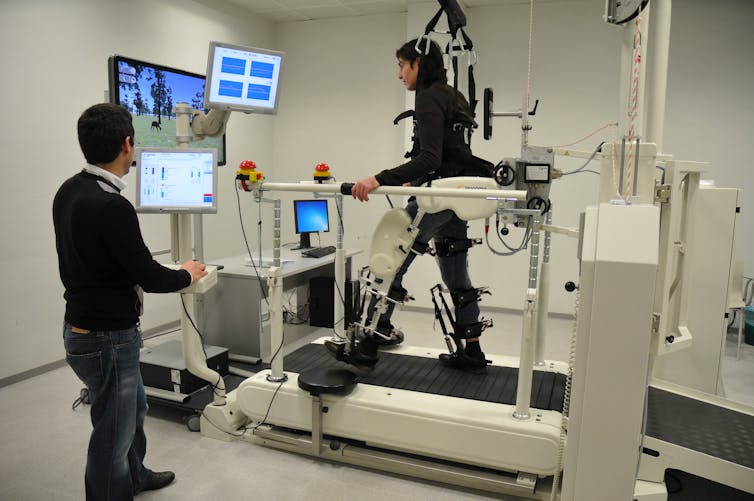

The relationship between humans and robots is now gradually evolving towards the third generation of interactions. Third-generation robots have the ability to interact cognitively or socially like so-called "social" robots, but also physically like exoskeletons.

Robots capable of providing physical assistance, which could be used for rehabilitation and elderly care, social assistance, and security, have also been clearly identified as a priority by governments in Europe, the United States, and Japan since the mid-2010s.

One way, in particular, to address the problem of aging populations in these developed countries.

Challenging the definition of the human body

We are now slowly seeing the emergence of a fourth generation of human-robot interactions, in which robots are not only physically close to humans, but also connected to the human body itself. Robots are becoming extensions of the human body.

This is the case with functional augmentation devices, such as robotic prosthetic limbs, or functional replacement devices such as robot avatars (which allow humans to use a robot body to perform specific tasks). Other devices can also provide humans with additional sensory perception.

Fourth-generation interactions are fundamentally different from other generations due to one crucial factor: prior to this generation, humans and robots were clearly defined in all their interactions by the physical limitations of their respective bodies, but this boundary becomes blurred in fourth-generation interactions, where robots modify and extend the human body in terms of motor and sensory capabilities.

In particular, fourth-generation interactions are expected to interfere with these "body representations." We know that there are specific representations of our bodies in our brains that define how our brains recognize our bodies. These representations determine our cognition and behaviors.

For example, imagine you are shopping in a crowded grocery store aisle. As you reach for items with your right hand, you are able, very implicitly and without even realizing it, to avoid your left arm colliding with other shoppers.

This is possible because your brain has a representation of the size and shape of your limbs and is aware of and monitors each of them. If you are holding a basket in your arm (which changes the size and shape of the "arm"), you will find it more difficult to instinctively avoid collisions and will have to make a conscious effort to ensure that the basket does not bump into anything in your immediate surroundings.

Similarly, can our brain adapt to a supernumerary limb, or other fourth-generation robotic addition, and update its bodily representations? This is what is known as "embodiment" in neuroscience.

If the embodiment of these devices can occur, how quickly does it happen? What are the limits of this embodiment? How does it affect our behavior and the brain itself?

Fourth-generation human-robot interactions not only challenge the user's brain's acceptance of the machine, but also society's acceptance of the user: it is still unclear whether our society will accept, for example, individuals with additional robotic arms. This will certainly depend on cultural aspects, which we are also trying to analyze.

In reality, third- and fourth-generation robots are so close to humans that we need to better understand human behavior and our brains in order to develop them.

In our work, we therefore combine research in robotics with cognitive, motor, and social neuroscience to develop what we believe to be the science of human-machine interactions.

It is only through a holistic understanding of human individuals, the machines that interact with them, and the society in which they live that we will be able to develop future generations of robots. And, in a sense, the society of the future.

Ganesh Gowrishankar, Researcher at the Montpellier Laboratory of Computer Science, Robotics, and Microelectronics, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.