Tardigrades in quantum land?

Biology, including "molecular" biology, has traditionally been the preserve of the comfortable classical sciences, while physics and chemistry have been infiltrated by the undulating and bewitching world of quantum physics. Recently, however, remarkable advances in biotechnology have made it possible to explore the quantum aspect of living organisms.

Simon Galas, University of Montpellier and Michel Cassé, French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA)

SciePro/Shutterstock

The term "quantum biology" covers the application of concepts from the physics of atoms and their components to biology, the science of cells and entire organisms. It finds its main application in enzyme-catalyzed reactions, photosynthesis, ion channels, olfaction, the navigation of migratory birds, and the infiltration of protons into DNA through the tunnel effect.

Does quantum mechanics, random and capricious, point to what gives life its momentum and charm? Does the entanglement, weaving, and embroidery of the biological and the elementary quantum promise to reveal the rules of fundamental life in the sense that we understand fundamental science? Does life require quantum mechanics? Yes, undoubtedly: we are made of atoms, and our physical and chemical machinery is molecular. But in a more subtle way, can we hope to shed light on phenomena that currently defy our understanding? In other words, does quantum mechanics play a fundamental role in biology? Does it have a physiological impact? And if so, what future biomimetic applications does it herald?

It is in this open technological context that small animals with four pairs of legs and unusual resistance, called tardigrades, come into the picture, under the pretext that they walk slowly. These animals have been the subject of a recent experiment that has made headlines and caused a stir in the quantum and biological communities, while leaving some researchers skeptical.

The embrace of the tardigrade and the qubit

Researchers in Singapore sought to quantum-link (known as entanglement) a cryogenically frozen tardigrade to a qubit (an essential component of superconducting circuits).

Electrons and photons behave in a non-conformist manner: we cannot say exactly where they are, or in which direction and at what speed they are moving. However, a mathematical tool called a "wave function" can be used to calculate where the electron or photon is likely to be and where it is likely to be heading. When well isolated and left to itself, a pure quantum state described by a coherent wave function evolves predictably, according to a mathematical prescription well established by Schrödinger. But when measurement occurs (in the broad sense of interaction with a macroscopic object), the state changes abruptly. The quiet evolution is interrupted and replaced by a roll of the dice. Schrödinger's equation, which is perfectly deterministic, gives way to Born's rule, which predicts the relative probabilities of various measurement outcomes, introducing an element of indeterminism and uncertainty. This conceptual catastrophe marks the transition between the quantum and classical domains.

Quantum entanglement refers to a relationship of dependence between particles that have interacted, no matter how distant they may be. It is then no longer possible to describe each of these particles correctly without including information about the other in the information about one. (Note: Schrödinger saw entanglement as the hallmark of quantum physics, while Einstein cursed it, calling it "spooky action at a distance.")

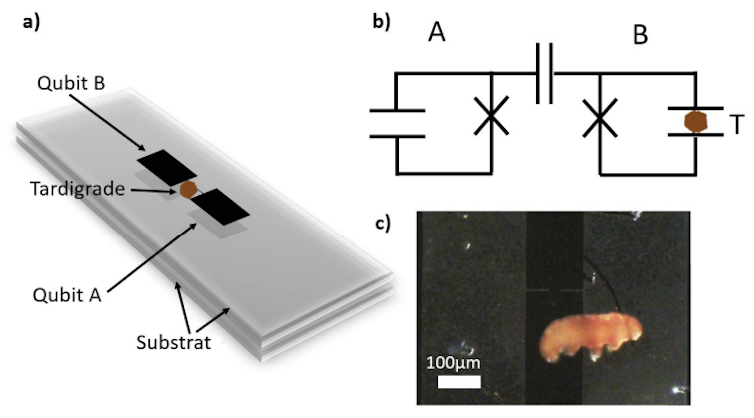

But let's get back to our tardigrades. In their experiment, Reiner Damke and his colleagues at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore integrated the tardigrade into a circuit composed of two superconducting qubits.

K.S. Lee et al./arXiv

Then, they gradually lowered the pressure and temperature of the chamber to create the most perfect laboratory vacuum possible, in order to reduce external influences on the qubits and the small animal. Finally, they measured the frequencies at which the tardigrade-qubit combination vibrated. The result? The protagonists were in a state of quantum superposition: their properties were no longer independent (in other words, information about one was necessary to describe the other, and vice versa).

Then, once the chamber returned to more natural temperature and pressure levels, the tardigrade was warmed up and came out of hibernation to resume its life. In other words, the little creature entered the collectivist, sharing, and impersonal quantum world, then returned to its solitary and well-differentiated state at the end of the operation, without seeming to have suffered from this strange journey.

Accolade, really?

Faced with this result, metaphysical questions flood the mind. What does "being entangled" mean for a living being? And marrying a metal object? This opens the door to all kinds of fantasies. To avoid wild speculation, it is best to put the situation into perspective.

First of all, the temperature and pressure conditions under which the experiment was conducted are extremely coercive. It is unlikely that they occur frequently in nature!

As for the tardigrade, it was cryogenically frozen, which changes everything! Ice acts as a dielectric, modifying the resonance frequency of the qubit on which it is placed. Observing a change in vibrational frequency was therefore logical, whether the ice was a frozen tardigrade or a simple ice cube, and any other material modifying the electric field would have produced the same result. To consider this as quantum entanglement would be equivalent to saying that a qubit, under normal conditions, is entangled with the silicon chip that serves as its support.

In short, we are still a long way from real quantum entanglement involving living organisms. Detractors claim that the achievement should therefore be attributed to the tardigrade rather than to the researchers...![]()

Simon Galas, Professor of Genetics and Molecular Biology of Aging, IBMM CNRS UMR 5247 – Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Montpellier and Michel Cassé, Astrophysicist and writer, French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.