Where does tap water come from? How is its quality ensured?

In France, turning on a tap to get drinking water is a particularly easy everyday task that gives us access to water of very good microbiological quality—which can be very useful, especially in the summer heat... However, in 2020, one in three French people continued to drink bottled water rather than tap water, even though plastic waste is harmful to health and the environment, bottled water is more expensive... and its quality is not always perfect. Let's take a look at where tap water comes from and what makes it safe to drink.

Alice Schmitt, University of Montpellier and Julie Mendret, University of Montpellier

Where does running water come from and how does it become drinkable?

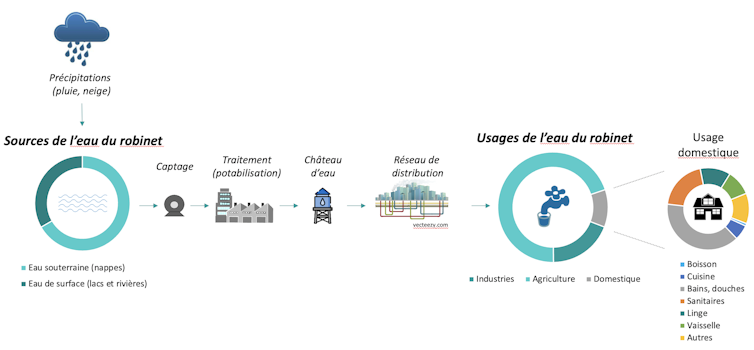

Two-thirds ofdrinking water is collected from groundwater (aquifers), with the remaining third coming from surface water (rivers, lakes, dams). Aquifers and rivers are fed by precipitation in the form of snow and rain, followed by runoff and infiltration.

Human activities such as agriculture and livestock farming and their consequences, such as deforestation, the destruction of wetlands, and climate change, cause significant changes in this cycle, particularly in the flow of water transported.

Alice Schmitt and Julie Mendret, Provided by the author

Once collected, the water is transported to a treatment plant for processing. The treatment applied depends on the initial quality of the collected water. For groundwater, in three-quarters of cases, simple physical treatment (filtration and settling) and disinfection are sufficient.

For surface water, more advanced physical and chemical treatments are required, depending on the quality of the water to be treated. In some cases, additional refinement treatments such as ozonation, activated carbon and/or membrane filtration are applied to remove as much of the remaining dissolved organic matter and micropollutants (pesticides, etc.) as possible.

Disinfection always takes place during the final stage of treatment, most often by adding chlorine, which has a long-lasting disinfecting effect, ensuring that the water remains of excellent quality during storage in reservoirs and until it is distributed.

In France, average per capita consumption of drinking water is estimated at around 150 liters per day, of which 93% is used for hygiene (including 20% for sanitation) and 7% for food. This domestic use accounts for 20% of overall consumption: 35% of drinking water is used for industry and electricity, and 45% for agriculture, although it is not necessarily necessary to use drinking water. The reuse of treated wastewater is still very limited in France due to strict regulations and remains a minority practice for these uses.

Highly regulated water distribution

Once treated, the distributed water must meet certain health standards defined by public health regulations, and its quality is regularly monitored from the point of exit from the water treatment plants, at the water towers where it is stored, and throughout the distribution network.

[Nearly 70,000 readers trust The Conversation newsletter to help them better understand the world's major issues. Subscribe today]

In total, around sixty parameters are monitored using bacteriological, physicochemical, organoleptic, and radiological limits and benchmarks, making tap waterthe most closely monitored foodstuff in France.

Overall, the quality of tap water in cities is excellent in France, where almost 100% of municipalities with more than 50,000 inhabitants and 98% of the total population consumed water of very good microbiological quality throughout 2020.

mrjn Photography/Unsplash, CC BY

With regard to pesticides, mainly from runoff and soil infiltration, 94% of the French population consumed water that complied with regulatory limits throughout 2020. However, as the exceedances detected were limited in concentration and duration, it was almost never necessary to impose restrictions on tap water consumption.

The risk of consuming low doses of pesticides on long-term health is still poorly understood but highly probable, particularly for sensitive populations such as children and pregnant women.

Occasional problems may arise in very small municipalities (fewer than 500 inhabitants); in rural areas with intensive monoculture or wine-growing agriculture that uses pesticides; in areas located near livestock farms, where nitrates may be present in significant quantities; or in areas located near certain industries.

If standards are exceeded, it is the responsibility of the production or distribution manager to take the necessary corrective measures to restore water quality.

Exceptional exemptions may be granted (if there is no health risk and with an obligation to quickly return to compliance) or strict measures may be applied very quickly if necessary by the prefect and followingthe advice of the relevant Regional Health Agency —for example , a restriction on use or even a temporary ban on consumption, as was the case in Châteauroux in June.

The presence of a water safety management plan, indicating the measures to be taken in the event of a problem, will be mandatory by 2027 thanks to the revision of the Drinking Water Directive of December 16, 2020.

Why use tap water instead of bottled water?

France consumes a lot of bottled water, as a result of lobbying by brands that have convinced the French that bottled water is better than tap water.

Erica Ashleson, Flickr, CC BY

The first priority is to protect the environment, as so-called mineral water requires the use of plastic bottles and caps as containers. Most of this waste (87%) ends up in the natural environment and becomes plastic pollution, which has a significant impact on aquatic flora and fauna. Sorting this waste in appropriate centers does not solve everything, as only a quarter of plastic waste is actually recycled worldwide. A study analyzing the life cycle of mineral water has shown that it sometimes has an environmental impact 1,000 times greater than that of tap water.

But it is also a public health issue linked to the presence of microplastics in water. These are mainly caused by the degradation of larger plastic objects such as bottles. Every week, we ingest the equivalent of a plastic credit card, mainly through the water we drink—from the tap and in bottles —but also, to a lesser extent, through the food we eat, particularly shellfish, and even the air we breathe (this is an estimated global average, not just for France).

Reducing or even eliminating the use of plastic, particularly by no longer consuming bottled water, would help reduce the presence of microplastics in the oceans.

In addition, certain types of highly mineralized bottled water should only be consumed occasionally, and daily use is not recommended. To neutralize the potentially unpleasant taste of tap water caused by chlorine, which does not affect its sanitary quality, a very simple solution is to let it breathe by leaving it in the refrigerator for a few hours before consumption.

It is also important to note that bottled water, which is sourced from underground resources, also contains trace amounts of pollutants such as pesticides and pharmaceuticals.

Finally, consuming bottled water for drinking (1.5 liters per day per person) is at least 100 times more expensive than drinking tap water.

We are fortunate in France to have high-quality tap water, so let's drink it, both for the sake of the planet and our health! You can find the average water quality in your municipality on your annual bill or at view online at any time.![]()

Alice Schmitt, Postdoctoral Researcher in Process Engineering, European Membrane Institute, University of Montpellier and Julie Mendret, Associate Professor, HDR, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.