[LUM#16] The mysterious case of the Thau bloom

Suddenly green waters, oysters that are wasting away and dying in droves, a disturbing disappearance... Strange things are happening in the Sète lagoon at the end of 2018. Curse or natural phenomenon? To unravel this mystery, the "Green Waters" project team investigated throughout 2019 to track down a tiny, tiny culprit. Its name? Picochlorum.

December 2018, the residents of Sète can hardly believe their eyes. The change happened in just a few days: the Thau basin turned green. Not greenish or watery green, no! Green! It came as a shock, as local oyster farmers had already been helplessly watching their oysters waste away for two months. In the laboratories that monitor the lagoon, there was a flurry of activity: "In the canals, everywhere, the water was green," recalls Béatrice Bec, a researcher at the Marbec marine biology laboratory. " A bloom like this in the middle of winter was impressive, but above all completely unprecedented in the Thau lagoon."

A disturbing disappearance

In technical terms, a "bloom" refers to the sudden and significant proliferation of microalgae within an aquatic ecosystem, generally caused by rising temperatures and/or nutrient inputs, and responsible for this green color. Very quickly, Béatrice Bec and a team of scientists, including Franck Lagarde, a researcher atIfremer, set up the "Green Waters"project to understand the causes of this imbalance. Starting in January, samples were taken every two weeks at three different points in the lagoon and at two depths. "The entire lagoon was affected, with concentrations never before seen here: one billion microalgae cells per liter of water sampled! That's starting to add up to a lot of suspects..."

Even stranger, analyses reveal the almost total disappearance of diatoms from the lagoon, a group of microalgae that constitute the main food source for oysters, which filter the water and retain them in their gills. Instead of diatoms, biologists are observing the massive presence of an unknown phytoplankton. "It looks like a tiny green ball, two to three micrometers in size , " explains Béatrice Bec. "This single-celled microalgae is so small that it is not retained by the oysters' gills, which in any case could not digest it because they lack the right enzymes." So much for the mystery of the skinny oysters, but the culprit still remains unnamed.

Such a small culprit

And for good reason: the microalgae are so small that biologists are unable to identify them under a microscope. To help them, they use molecular analysis, and it was CNRS researcher Ariane Atteia who managed to identify the culprit. Its name: Picochlorum! "This picophytoplankton has already been identified in the Adriatic Sea, around Roscoff, and in the waters of the Côte Vermeille, but never in such proportions. It can live in a fairly wide range of temperatures and salinities, which has allowed it to thrive in winter conditions. But why such a bloom, and why now? What exceptional factors have allowed it to emerge? These are questions that haunt the inhabitants of the lagoon as the weeks go by, the waters remain green, and the oysters remain thin.

To answer this question, scientists are examining data compiled by REPHY, Ifremer's phytoplankton observation and monitoring network responsible for monitoring the lagoon, and comparing the 2018 analyses with those of previous years. The first observation is that the summer of 2018 was marked by malaïgue, or "bad water" in Occitan. "Malaïgue is a bit like the lagoon having a liver crisis due to being overfed with nitrogen and phosphorus. These anthropogenic inputs promote excessive growth of macroalgae, which, as they degrade, cause an imbalance in oxygen levels in the absence of wind and in high temperatures. This malaïgue has led to a destabilization of the diversity and abundance of phytoplankton communities," explains Béatrice Bec.

A close synergy

With the September winds blowing away the malaïgue, the story could have ended there, except that 2018 was also a very rainy year, marked by a succession of storms and thunderstorms. These natural phenomena, once again, contributed to an additional supply of nutrients in the lagoon. "What we observed in retrospect is that, starting in August, Picochlorum was quietly present in the lagoon, which was already destabilized by the malaïgue. It was able to take advantage of a synergy of exceptional climatic and environmental events that ultimately led to this bloom."

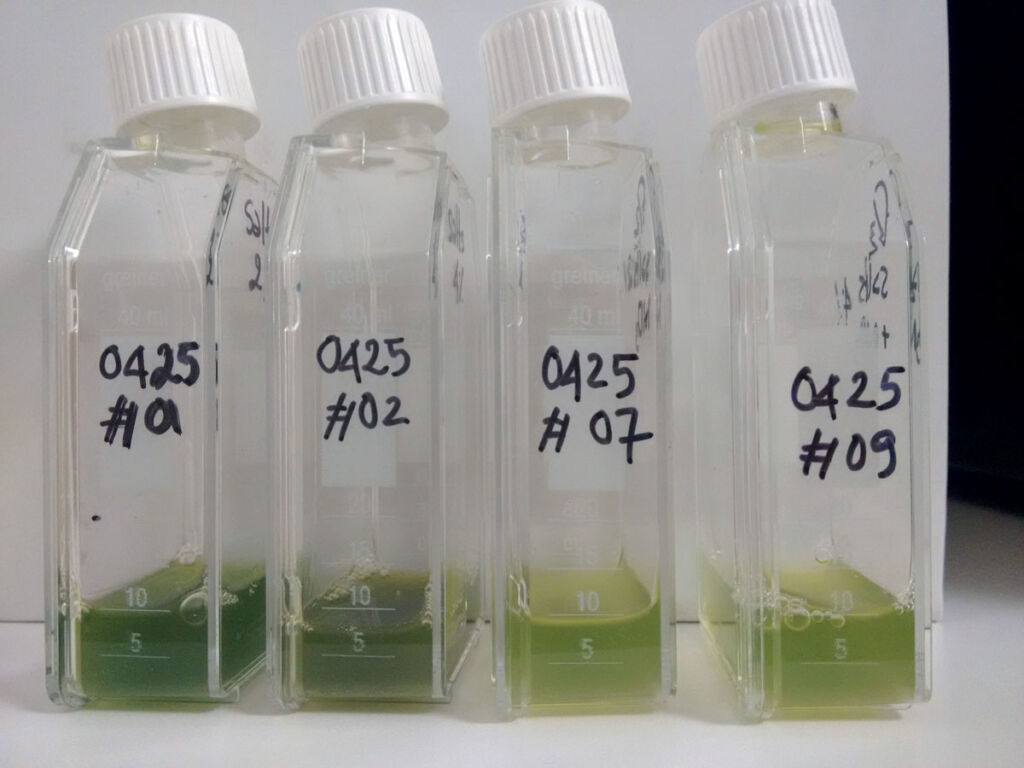

In the end, the humans of the lagoon, like the oysters and diatoms, had to wait a year for their ecosystem to naturally regain the deep blue of its waters. Picochlorum, meanwhile, is serving its sentence at the Marbec laboratory, where experts are taking turns trying to get it to talk: "We have isolated a strain and are testing its physiological capabilities, nutritional needs, preferred temperatures, and so on. Another objective is to develop molecular tools to probe the lagoon and potentially set up a warning system against this tiny but highly resistant invader. "We even had fun depriving it of oxygen... It's doing very well," concludes Béatrice Bec.

* Marbec (UM – CNRS – IRD – Ifremer)

Find UM podcasts now available on your favorite platform (Spotify, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, etc.).