Price is not necessarily a sign of product quality

Do prices tell us enough about the quality of the goods or services we buy? The question remains unanswered for a category of goods that economists call credence goods, to indicate that the value of these goods is based on the trust that the buyer places in the seller.

Philippe Mahenc, University of Montpellier

The quality of a fiduciary good includes a component that responds to a public concern of an environmental, ethical or health nature. An ecological or fair-trade label enhances the value of a fiduciary good by proclaiming that its production and/or distribution comply with more or less precise standards.

It is not easy to verify that a company meets these standards: only an expert can certify - often with a margin of error - that the company is trustworthy. As a result, the buyer can never be sure of being properly informed about the quality of a trust asset, even after consuming it. Contractors may then be tempted to abuse his trust.

To dispel buyer uncertainty, producers and distributors of a fiduciary good need to find a credible way of signalling its quality, such as price.

Sometimes a company will sell a product at a particular price - high or low - to signal that it is of good quality, as we showed in a research article published in 2007. Sometimes, however, the price of a fiduciary good fails to send a credible signal, as the following three examples from the wine, automotive and healthcare sectors illustrate.

In 1907, winegrowers fall victim to fraudsters

Before the law of June 29, 1907 protected natural wine from adulterated wine, the French wine market was disrupted by the supply of piquette. According to this law, wine must derive exclusively from the alcoholic fermentation of fresh grape juice. In the absence of an official definition, wine was a fiduciary good.

To make piquette, grape marc was pressed and diluted with water, or the color and taste of bad grape juice was enhanced with chemical additives. Merchants and winegrowers who engaged in this unfair competition accounted for around 5% of the market.

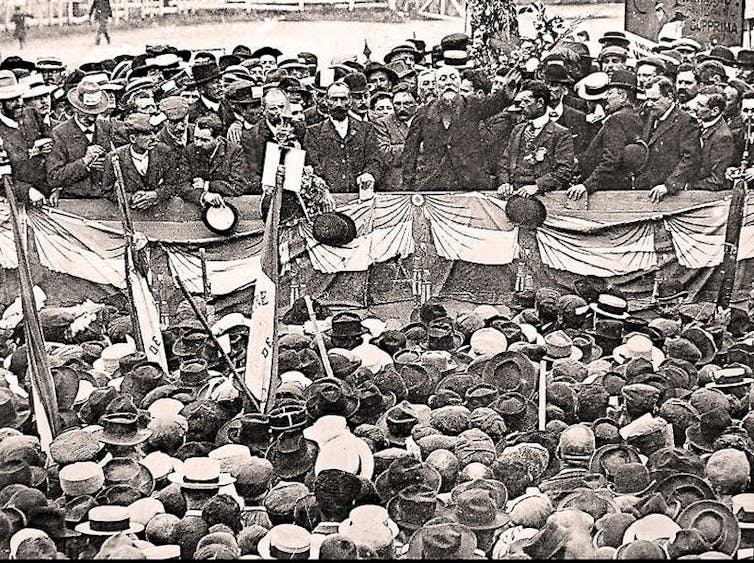

Wikimedia

When wine prices collapsed in France after 1900, winegrowers in the Midi region blamed adulterated wine. Small winegrowers in the Languedoc and Pyrénées-Orientales regions were ruined by the poor harvest of 1906. The wine crisis sparked a spontaneous revolt in 1907, which was bloodily suppressed by the government.

In this case, the market price was the same, whatever the quality, so that it was impossible to distinguish natural wine from piquette. Under these conditions, it was not absurd to think that bad wine was dragging good wine down with it.

Subsequently, the law of June 29 and the associated decrees made it possible to organize fraud prevention and control. They gave authority and the means to ensure compliance with standards to a body representing the interests of winegrowers, the Confédération générale des vignerons.

Volkswagen's opportunism

More recently, opportunistic behavior has appeared on the European diesel vehicle market. Using misleading advertising, carmakers claimed that their "Clean Diesel" diesel engines were environmentally friendly.

In 2015, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency accused the Volkswagen Group of violating the Clean Air Act's Clean Air Act, based on a report by the International Council on Clean Transportation. This organization highlighted differences in nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions between American and European vehicle models.

See also:

Volkswagen's irregular competition

It was thus proved that Volkswagen had equipped its diesel cars with software programmed to evade pollution controls. After passing laboratory tests, the vehicles emitted up to 40 times more NOx on the road than the American standard. Volkswagen pleaded guilty in 2017.

Other independent tests carried out by the German automobile club ADAC have shown that in real-life driving conditions, Volkswagen's rival diesel engines exceed the legal NOx emissions threshold in Europe by more than 10 times.

Among vehicles with the same technical characteristics, if there is one that stands out from the crowd for being less polluting, its price must signal this by a singularity. Depending on sales prospects, this singularity takes the form of a discount or an increase that a dishonest manufacturer would be unable to offer. In this way, the signal lends credibility to the model's advertising.

Laboratories guilty of dishonest communication

The third example of opportunistic behavior is provided by three pharmaceutical companies, Genentech, Novartis and Roche (GNR). The trio markets two anti-blindness drugs, Lucentis and Avastin, which do not target the same symptoms. Lucentis treats age-related macular degeneration (AMD), while Avastin treats cancer caused by diabetic macular edema.

Unlike Lucentis, Avastin does not benefit from a marketing authorization for ophthalmological treatments. It is nevertheless prescribed to slow the effects of AMD by a large number of doctors convinced that the treatment is as effective as Lucentis. The UK's National Health Security reached the same conclusion in 2018.

Moreover, Avastin has a decisive economic advantage over Lucentis: it is sold 30 to 40 times more cheaply worldwide. GNR's price differential sends out some rather disturbing signals.

In 2013, the French Avastin versus Lucentis Study Group also demonstrated the equivalence of Avastin and Lucentis in terms of efficacy, with no difference identified in terms of safety.

In response, GNR ran a communications campaign based on a selective and biased presentation of scientific results, with the aim of misleading ophthalmologists about the risks associated with the use of Avastin. Finally, in September 2020, the French Competition Authority sanctioned Genentech, Novartis and Roche for abusing their collective dominant position in the French AMD treatment market. Among their grievances, the trio were accused above all of dishonest communication methods.

In these three examples, prices did not reveal any information about the real quality of trust assets. They supported opportunistic behavior rather than deterring it. Admittedly, prices sent signals, but these signals were not credible, since they did not distinguish the right quality.

Sending credible signals

As we showed in a research article published in 2017, it is therefore necessary for price signals to be credible to guarantee the reliability of certification.

It's easy to see why prices didn't send out credible signals in the case of French winegrowers. They were too small to decide on prices that were imposed on them by competitive pressure.

On the other hand, car manufacturers or pharmaceutical companies enjoy sufficient market power to choose their prices strategically. They set the price of a product all the higher because they expect competitors, if any, to act in the same way. When products are fiduciary, manufacturers can also use prices to signal quality. As we have seen, they sometimes prefer to mystify buyers.

The existence of such strategies is food for thought at a time when pharmaceutical companies are advertising the efficacy of various Covid-19 vaccines in order to segment the market and prepare for price competition. This raises the question: do the prices offered to purchasing countries really reflect the efficacy of the vaccines?![]()

Philippe Mahenc, Professor of economics (environmental economics/industrial organization/agricultural economics), University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read theoriginal article.