The isolated National Rally: the failure of Le Penism at the municipal level

For the National Rally, this municipal election promised to be one in which it would establish its roots.

Emmanuel Négrier, University of Montpellier

It promised to be very different from that of 1995, when symbolic victories in cities such as Toulon, Marignane, and Orange proved to be exceptional and fragile cases: short-lived in electoral terms for Toulon and Vitrolles, and complicated for the party elsewhere, with the defections of well-established elected officials such as Jacques Bompart in Orange and Daniel Simonpieri in Marignane.

This election also promised to be different from that of 2014, which was marked by significant gains, particularly in the two main areas of influence of the far right: a vast northeastern region stretching from Hénin-Beaumont to Villers-Cotterêts via Hayange; and the Mediterranean coast, notably Béziers, Fréjus, and Beaucaire.

However, nothing went as planned, and it is clear that the RN finds itself in a very complicated situation at the dawn of this second round.

A double challenge

This time, there were two challenges. The first was to hold on to the town halls won in the last municipal elections, in circumstances that were sometimes unusual, notably a high degree of fragmentation among the opposition, without being able to count on a significant reserve of votes.

The second was to translate the successes achieved by the party in the 2015 regional elections, the 2017 presidential elections, and the 2019 European elections, where the party had come out on top, to this very specific scale.

To achieve this, the National Rally opted for a three-pronged strategy: establishing local roots; overwhelming and recruiting the right wing; and softening its rhetoric. These three pillars of the rise of the far right constituted Bruno Mégret's "posthumous" victory over Jean-Marie Le Pen, who had always been resistant to even the slightest political autonomy for his local elected officials.

They were intended to enable the party to increase its number of representatives at the local level and, even if victory was not always guaranteed, this pool of candidates at least made it possible to envisage certain favorable outcomes in the next senatorial elections.

This strategy was particularly evident in Perpignan, where Louis Aliot had strengthened an already significant presence by winning the seat of deputy for the2nd district of the Pyrénées-Orientales in 2017. Above all, the tone of his campaign revealed a good-natured leader, whose moderate discourse contrasted sharply with the radically right-wing views of the outgoing LR mayor.

She found an almost embarrassing supporter in Robert Ménard who, from Béziers, is thinking more and more clearly about the world after Marine Le Pen. Having attempted and failed to bring together the radical right ideologically with the "Ose ta droite" event, has shifted his tactics toward electoral overflow, advocating for the synthesis of the right in Sète (endorsement of the departmental secretary of Les Républicains) and Frontignan (support, in the name of the same axis, for Front National candidate Gérard Prato), while Thierry Mariani, former minister under François Fillon, did the same in Lunel.

Resounding failure and setback in the first round

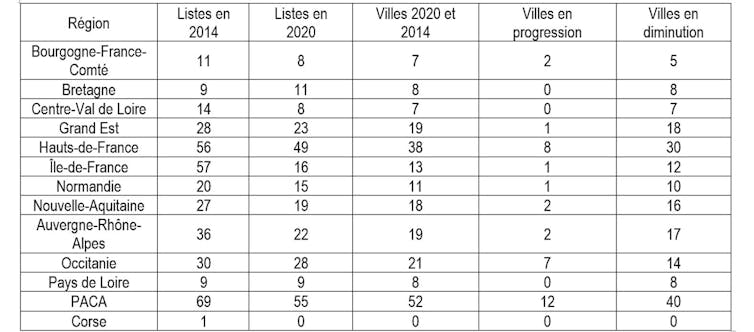

The result of this strategy of raising the party's profile has been a resounding failure, full of paradoxes. To attribute this to the health crisis would be a gross exaggeration. The failure predates March 15, 2020: indeed, we note that the RN did not even manage to present as many lists in towns with more than 10,000 inhabitants as it did in 2014. Far from it: only 262 lists, compared to 369 in 2014!

The Jean Jaurès Foundation kept a precise record of the results of these lists, which were fewer in number but—it was promised—of higher quality and more attractive to voters in the first round.

The result is clear. The RN is in decline in all regions, even those where it enjoyed considerable electoral support, as measured by the results obtained in 2017 (presidential) and 2019 (European) elections, where it exceeded 50% of the vote in a large number of municipalities (Occitanie, PACA, Hauts-de-France, Grand Est).

The first paradox, then, is that the RN failed to extend its influence even though it enjoyed extremely favorable conditions. In southern cities, where its chances appeared all the stronger given its pool of candidates who had been running in the same areas for several years, its decline is striking.

He lost a third of his influence in Nîmes, and more than half in Saint-Gilles, his first stronghold in the late 1980s, a town he had almost recaptured with Gilbert Collard in 2014. In addition to the towns where he failed to field candidates, his scores were down significantly in Frontignan (28%, 2 points and 800 votes less than in 2014). In Montpellier and Toulouse, the two major cities, he even fell below the 5% threshold, meaning that his election expenses will not be reimbursed.

In Sète, a hotbed of right-wing fusion à la Ménard, the notable Sébastien Pacull, outgoing deputy who rose through the ranks and was endorsed by the RN, won... 14.4% of the vote, exactly the same percentage as in 2014, but with 900 fewer votes due to abstention. The aim was to break down the barriers, but they seem to have been reinforced in these towns where victory was expected.

Victories for the incumbents

The second paradox is that while it is losing ground in areas where its most reasonable hopes were forged—with the exception of a few cases such as Moissac in the Tarn, where it doubled its score and is very well placed to win in the second round—the RN is achieving resounding victories in areas where it was the incumbent.

Beaucaire, Béziers, Fréjus, among many others, had been won in specific contexts of pathological division among the opposition, and in three-way races in the second round without reaching 50% of the vote. Here, the re-elections are masterful, as in Hénin-Beaumont, Hayange, Villers-Cotterêts, and Le Pontet.

But they only confirm the exceptional nature of RN municipal leadership, both nationally and locally. It is therefore remarkable that these successes do not, in most cases, lead to expansion at the intermunicipal level, where there are increasingly more resources available to influence public policy.

Julien Sanchez triumphs in Beaucaire, but will not be able to govern the Terres d'Argence community of municipalities. Steve Briois faces the same problem in Hénin-Beaumont.

Political singularity

Ultimately, the RN, which wanted to normalize itself through these elections, has only reinforced its political singularity and, as a result, its isolation. Why?

To put this election episode into perspective, we will have to wait for the results of the second round, where he is still in a position to hold on to 136 municipalities (compared to 317 in 2014). But we can already identify the following three trends.

- If the RN fails to take root at the municipal level, it is because neither voters nor potential candidates see it as a party like any other. Although it presents a moderate discourse, it still gives off a whiff of sulfur. The best proof of this comes from surveys: RN voters, like FN voters in the past, are the only ones who feel the need to justify themselves when asked who they vote for. To overcome this, voters cannot be satisfied with representation alone. They need experience in power. And the leaders of the 2014 vintage, unlike most of their predecessors, have skillfully used communication, symbolic operations, and a hyper-presence on the ground.

- The health crisis obviously played a role among voters who, in the past, had switched their allegiance to European lists or the RN's legislative and presidential candidates. Much has been said about the shock effect that gripped voters on March 15, strengthening the advantage of the incumbents and disqualifying the most "disruptive" opposition parties. There is undoubtedly some truth in the idea that episodes of extreme gravity have a negative impact on parties that feed on negative emotions: hostility towards others, feelings of decline, loss of collective reference points, etc. The prevailing sentiment on March 15 was more on the side of "joyful" passions of mutual aid, solidarity, and the need for common goods. But the damage to the RN goes far beyond that. If there is a structural distortion between European success and municipal disappointment, it is because even for its supporters, the RN remains undesirable "at home." This is the paradox of the Front National's illegitimacy. To ward off this curse, the decline of the local right (and left) would have to be accompanied by the rise of a providential man who knows how to make the most of this fertile ground. By definition, this remains exceptional.

- It would therefore be wrong to view this failure as a more general setback for the RN. If the far right continues to perform well in municipal elections, it is because it is partially disconnected from the causes and dynamics that make it successful at other levels, as researchers Jean-Yves Camus and Nicolas Lebourg recently demonstrated in Europe.

The turmoil of negative emotions, the cultivation of simplistic solutions, and the lack of investment in culture and education in post-COVID-19 Europe and France are all factors that could fuel the narrative of the radical right.![]()

Emmanuel Négrier, CNRS Research Director in Political Science at CEPEL, University of Montpellier, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.