Wine labels aren't (always) a mystery!

China remains one of the most promising markets for the wine industry. According to a recent study, the country is expected to be the second largest consumer market worldwide in 2021.

Franck Celhay, Montpellier Business School – UGEI and Josselin Masson, University of Montpellier

The main exporting countries must understand this customer base in order to try to establish themselves there. In particular, they need to think about creating label designs that are as "expressive" as possible.

It is generally accepted that the graphic choices made in packaging design communicate values, a promise, and even a brand story to consumers. However, one question remains: how is this visual language understood when packaging is exported to a culturally different country, such as China?

Signs that are understandable across cultures

To answer this question, we conducted research exploring Chinese consumers' interpretation of eight wine label designs. These eight labels, created by a French graphic designer, aim to communicate eight brand narratives frequently observed in mainland China: "festive" wine (bottle 1); "romantic" wine (bottle 2), "ancestral" wine (bottle 3); "liberating" wine (bottle 4); "natural" wine (bottle 5); "rustic" wine (bottle 6); "poetic" wine (bottle 7); and finally, "chateau" wine (bottle 8).

Two empirical studies were then conducted among Chinese consumers to verify their perception of wine bottles using a free word association task. The first study was conducted on a sample of 1,391 consumers of imported wines with labels indicating the origin as "Bordeaux." The second study was conducted on a sample of 795 respondents, including non-wine consumers, with labels where the origin of the wine was concealed (see Figure 2).

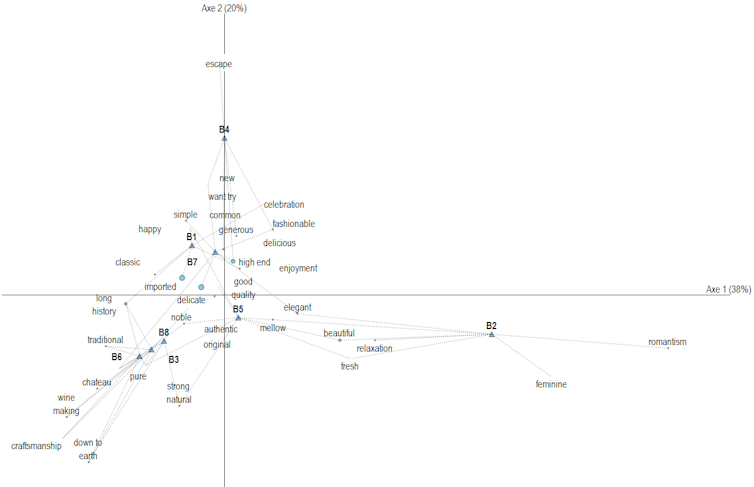

For each study, respondents were asked to evaluate four bottles presented in random order. A total of 5,564 and 3,180 responses in Mandarin were collected as part of the two studies. The responses were translated from Mandarin into English and then analyzed using Sphinx Quali software (see Figure 3).

The map shown in Figure 3 reads as follows: the position of the different bottles is indicated by triangles and labeled B1 to B8. The words on the map indicate the different associations of ideas generated by the different bottles. When the bottles are far apart on the map, it means that they generate different associations of ideas and are clearly differentiated (for example, B4 associated with the theme "escape " or B2 associated with the theme "romance"), when the bottles are close to each other on the map, it means that they share a number of associations and communicate similar brand images (for example, B3, B6, and B8 are associated with the themes "tradition" and "seniority").

The motivation behind the signs

The results reveal that, for 7 of the 8 bottles tested, Chinese respondents were able to understand the French designer's communication intent, even among people who are unfamiliar with wine culture or Western culture.

The explanation lies in the fact that the seven "understood" bottles use "motivated" signs, while the "ununderstood" bottle uses "arbitrary" signs . A motivated sign is a sign whose meaning is based on a certain logic. It is therefore possible to guess its meaning without having learned its meaning beforehand. Such signs can remain intelligible across cultures. Conversely, an arbitrary sign is a cultural convention and is not based on any form of logic. Therefore, it is not possible for someone from another culture to guess its meaning.

For example, bottle 3 (the "ancestral" wine) is spontaneously associated with themes such as "age" and "tradition" (Figure 3). This bottle uses yellowed paper for its label. This is a case of a motivated sign, as paper yellows with age. The association between "yellowed paper" and the notion of "age" is therefore based on a form of logic that remains intelligible to any culture that has mastered paper production.

Conversely, to convey the idea of a "poetic" wine (bottle 7), the designer chose to reproduce a poem on the label in a fast script font reminiscent of an artist's penmanship. From the perspective of Chinese respondents, neither the reproduction of the poem nor the font can be considered as motivated signs. With the exception of those who have learned French, Chinese consumers cannot read the content of the label and therefore cannot understand the poetic nature of the text reproduced. Similarly, they cannot understand the meanings associated with different styles of Latin fonts since they use a different writing system.

The challenge of "localized" packaging

These results are interesting because they challenge: (1) the idea that visual signs necessarily have different meanings from one culture to another, and (2) the resulting recommendation that it is essential to "localize" packaging, i.e., adapt its design to the different cultures to which it will be exported.

This idea is generally based on the well-known example that white has positive connotations in Western countries (such as purity) but negative ones in Asian countries (such as death). While this example has the merit of being striking and drawing attention to the notion of cultural differences, it is also overly simplistic and therefore produces a general recommendation (localize packaging) that is not always relevant.

In most cultures, colors have both positive AND negative meanings, which may or may not be activated depending on the context and how they interact with other signs. For example, white can ALSO refer to death in the West if we look at the visual representation of near-death experiences (white light at the end of the tunnel) or ghosts (white shroud). Furthermore, in many market situations, consumers (whether Asian or Western) seek to consume products that they perceive as exotic. Localizing packaging in such situations leads to a loss of perceived authenticity and reduces the appeal of the product.

Our results show that packaging design can remain intelligible across very different cultures if it uses meaningful symbols. It is therefore possible to create a design that remains true to its origins while remaining understandable in export markets.

Furthermore, the results indicate that Chinese consumers may appreciate label styles that differ from the classic "chateau" wine (see bottle 8). Indeed, all labels are associated in equal proportions with the themes of "high-end" and "good quality" (in the center of the map shown in Figure 3). It therefore seems possible to diversify the positioning strategies for French wines by adopting more varied label designs. This would make it possible to better respond to the diversification of Chinese consumer segments revealed by various recent studies.

Peiyao Cheng, researcher in the design department at Harbin Institute of Technology, and Wenhua Li, researcher at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Art, contributed to this article.![]()

Franck Celhay, Associate Professor, Montpellier Business School – UGEI and Josselin Masson, Senior Lecturer in Marketing, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.