UM researchers win gold in Boston

For the second consecutive year, a team of UM students has won a medal inIGEM, the major international synthetic biology competition organized by MIT.

The 14 students, who were in Boston on November 5, worked on a new medical molecular tool: protein scissors that could have numerous therapeutic applications. Project name: Karma!

Derived from Sanskrit, the term karma could be translated as "action." This word perfectly sums up the energy of this new team from Montpellier, which took part intheprestigiousInternational Genetically Engineered Machine competition(IGEM). In Boston, it defended its project against 340 teams selected from 40 countries, including Stanford and Oxford.

Elsa Frisot is a PhD student at the Center for Structural Biochemistry (CBS). She participated in last year's competition with the Vagineering project and wanted to repeat the experience, this time as a supervisor. "We selected the candidates based on their applications in January. Many biologists apply, but all students can participate. We need computer scientists, communicators, lawyers, graphic designers, and more."

Targeting proteins

Once the team had been formed, the fourteen young researchers had to develop a research project. Inspired by the CRISPR Cas9 tool, a genetic scissor that can target and cut a specific DNA sequence, they came up with the idea of designing a molecular tool that functions like a protein scissor.

"In many diseases such as cancer or Alzheimer's, research has identified the role played by certain proteins in the development of the disease," explains Thomas Bessede, a student in the BIOTIN Master's program (Master's in Health Biology). Current drugs use chemical molecules to break them down. The problem is that these molecules do not always destroy only the proteins in question and therefore cause side effects.

Molecules capable of breaking down proteins also exist in our bodies: these are called proteases. Some of them are highly specific and can effectively target a particular type of protein. "Unfortunately, " explains Elsa Frisot, " we don't have a specific protease for each type of protein. There are non-specific proteases, but these too can cause side effects."

A head-seeker

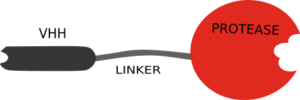

The students then came up with the idea of combining these non-specific proteases with antibodies, which are specifically designed to target a particular protein. "Today, in the lab, we are able to design antibodies for anything. Each antibody has the ability to bind to a specific target thanks to a small part called the VHH," explains Thomas Bessede. A VHH acts as a kind of "seeking head," which the IGEM team merged with the protease in order to bring it to the desired target.

To test this concept in the laboratory and prove that their scissors were indeed capable of cutting a protein at the desired location, the biologists had only three months to work with—a real challenge! They used GFP, a protein capable of emitting green fluorescent light, to which they added a small tag that blocked this fluorescence. "Our VHH was designed to target a specific motif on the tag. The goal was to guide our protease to this tag in order to break it down and allow the GFP to shine again. That's what happened, so we proved the concept," Thomas says happily.

Proof of concept

The experiment was then confirmed using the same VHH, but this time replacing GFP with another protein. "Since our VHH was designed to specifically target GFP, it should not have had any effect. Once again, we confirmed our proof of concept," concludes the biologist.

Although Montpellier did not expect to win the Grand Prize in the face of competition from major Anglo-Saxon universities, they were nevertheless aiming for a gold medal. And that's exactly what they got! "It's a great project and we met all the criteria!" Criteria that go beyond the scientific dimension of the project. The MIT competition also seeks to highlight other aspects of research, such as fundraising from private and public partners, website development, and scientific communication.

A "caravan tour"

"All summer long, we promoted science to the general public by traveling around the region in a caravan," explains Elsa Frisot. The team also covered the ecology aspect by working with students from Nantes to create an educational work of art from all the waste generated by their experiments. "In just three weeks, we generated 20 kg of plastic. Science pollutes a lot, so we also wanted to raise awareness of this lesser-known aspect of research," emphasizes Thomas Bessede.

Recognized and awarded, the KARMA project is now waiting in the CBS refrigerators in the hope that a motivated researcher will continue the experiment to fully develop its potential. You can read about this adventure on theIGEM 2019 website.