[LUM#22] In search of lost glaciers

Geologists use satellite images to study glaciers. This is a long and tedious task, which Isabelle Rocamora aims to simplify by developing the very first deep learning model dedicated to mapping glacial moraines.

Most of the fresh water on the surface of our planet is found neither in rivers nor in lakes, but in glaciers. Although there are still nearly 200,000 of them, many have disappeared and those that remain are melting like snow in the sun. During the 20th century, the glacier surface area decreased by 30 to 40% in the Alps, 75% in the Pyrenees, and even more than 80% in certain tropical mountain ranges such as the Andes and Kilimanjaro.

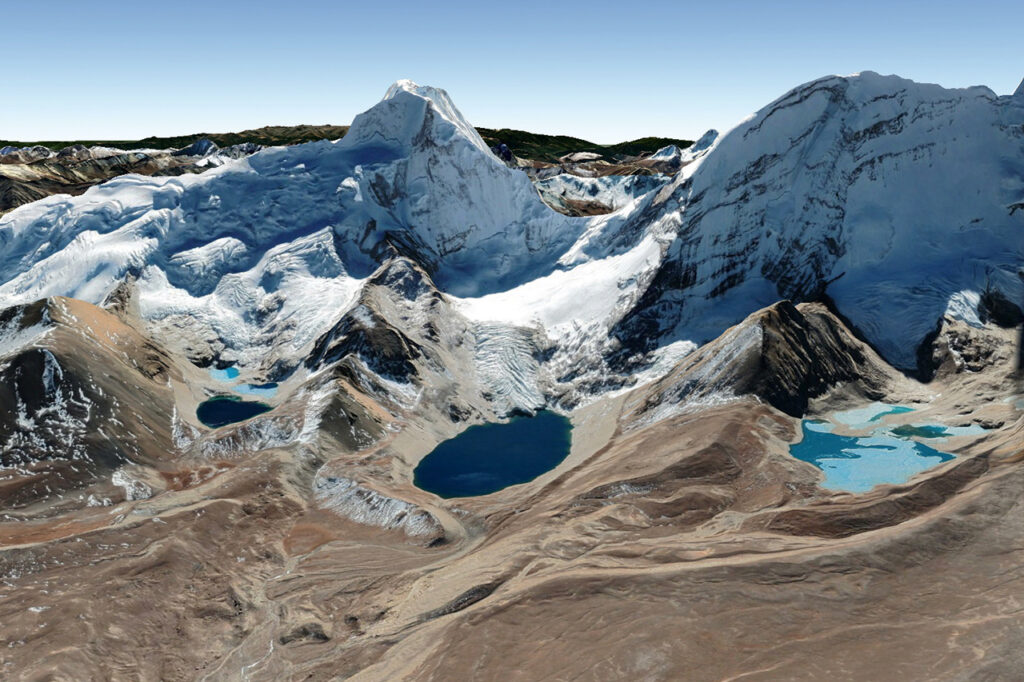

Glaciers that retreat still leave traces of their passage: geological formations called moraines. "They are piles of rock debris carried by the sliding movement of glaciers and accumulated at the bottom and sides, " explains Isabelle Rocamora. "It's like when you push sand with your hand and then remove it, leaving ridges of sand in front and around the edges," says the PhD student, who is conducting interdisciplinary research between the Montpellier Geosciences1 and Tetis laboratories, under the supervision of Matthieu Ferry and Dino Ienco. Mapping these moraines therefore provides valuable information, particularly on glacier retreat.

Automate tasks

A necessary but particularly time-consuming task: "To create this map, we will take measurements in the field and then search for glacial moraines on satellite images, which provide a broader view, " explains the geologist. To save time, she proposes automating this task using artificial intelligence. "I have developed an algorithm that can analyze satellite images. It is the first deep learning model dedicated to mapping glacial moraines."

To teach her software, called MorNet, to recognize a moraine from other rock formations, Isabelle Rocamora began by creating a "traditional" map using satellite images of the Himalayas acquired by the CNES Pléiades satellite. "I then fed these maps into the software, telling it 'this is a moraine' or 'this is not a moraine'. " The model then determined the common characteristics between the samples in order to learn how to identify a moraine on satellite images on its own. "A computer doesn't 'see' things like a human does, so rather than giving it human answers, we let it find its own identification rules, " explains Isabelle Rocamora.

Background information

To measure MorNet's performance, the geologist then compared her own mapping with that produced by artificial intelligence. While MorNet proved effective at recognizing moraine ridges, it was less successful at identifying their flanks, meaning that the model knows where these geomorphological formations are located but cannot clearly delineate them. This is because a moraine is not defined solely by its shape, but also by its formation pattern, which MorNet cannot see. To improve it, contextual information would need to be provided. "While deep learning saves time, mapping still requires the eye of a geomorphologist to confirm and refine the machine's conclusions, " concludes Isabelle Rocamora.

Find UM podcasts now available on your favorite platform (Spotify, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, etc.).

- GM (UM, CNRS, U Antilles)

↩︎