[LUM#7] Major soils

Preserving our Mother Earth: this is the essential challenge facing agriculture today. To meet this challenge, scientists are studying the cradle of crops: the soil. An ecosystem of unsuspected complexity...

"It isimpossible to understand soil if you separate it from its context, "warns Robin Duponnois, a microbiologist specializing in soil and president of the French Scientific Committee on Desertification. " Only a comprehensive approach can help us understand these highly complex phenomena."

Vital symbioses

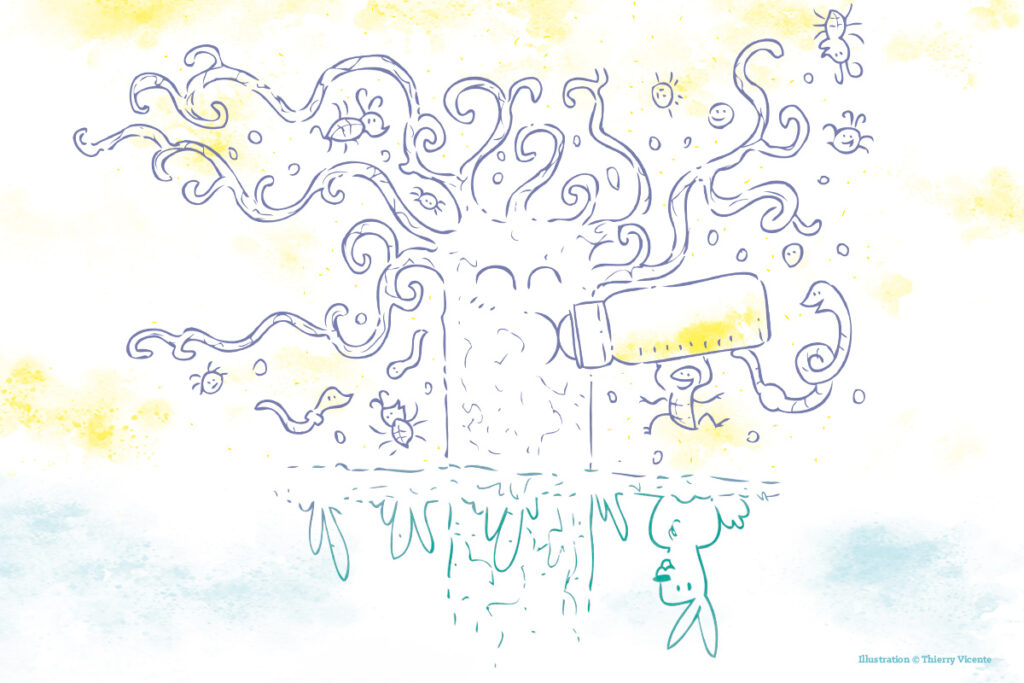

A brief overview of the complexity involved: without the plant cover that provides the basic material for the underground life cycle—dead leaves and other plant debris—and without the countless hidden inhabitants of the soil, insects, microscopic fungi, and other symbiotic bacteria, which are the only organisms capable of transforming this material (see box), there would be no hope for the plant.

Because it does not live on sunshine and fresh water alone. And it is anything but self-sufficient. On its own, it can only access the nutrients closest to its roots. This is not enough to ensure its growth... Fortunately, mycorrhizal fungi1 work to colonize these same roots thanks to their "hyphae," fine filaments capable of exploring a large volume of soil—thus providing access to infinitely more nutrients (Mycorrhizal associations in soils, for better control of plant production, in Soils and Underground Life, 2017).

More surprisingly, these same fungi act as nursemaids: " Complex organic or mineral moleculesare found in the soil that cannot be directly assimilated. The fungus 'digests' these large molecules, then uses its hyphae to transfer the recycled nutrients to the plant." In exchange, the fungus receives carbon from the plant, which is much better placed than it is to extract it from the atmosphere. Plants therefore form inextricable interconnected networks with their fungal friends. And they can only grow thanks to this symbiosis... unless its absence is compensated for by the artificial addition of mineral fertilizers.

From the "green revolution" to agroecology

It is true that fertilizers can easily boost plant growth: basically, you add a soluble mineral to the soil... and it grows. This is the long-standing idea behind the "green revolution ": growing varieties selected for their optimal production capacity, with the help of fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation, and machinery, while favoring large-scale single-variety cultivation.

What impact does this have on the soil and the environment? At the time, no one asked this question. This was the 1960s, just after the great famines. The goal was clear: to produce large quantities of food. This revolution was green in name only. Costly in terms of water, chemicals, and oil, industrial agriculture had serious drawbacks, chief among them the depletion of biodiversity, a major pillar of food security.

Imitating nature

Times have changed: scientists are now calling for agriculture that can simultaneously feed people and respect the environment. The first law of this "agroecology" is: "Intervene as little as possible! And apply natural biological processes—those at work in a forest. For example, reintroducing vegetation cover by replanting trees; promoting the action of soil microflora (mycorrhizal fungi, nitrogen-fixing bacteria, etc.); or enhancing the symbiotic capacities of plants among themselves." (Restoring tropical and Mediterranean soil production. The contribution of agroecology, IRD publication, 2017)

An approach that is as humble as it is pragmatic. "We try to observe traditional practices that are well suited to the realities on the ground, in order to help optimize them. Family farming has many positive characteristics: small areas, endemic species and multi-species crops, local know-how and low irrigation... If we want to ensure food security in developing countries, it clearly offers a model for the future," says Robin Duponnois.

Underground oases

"A single teaspoon of soil from your garden can contain several million living organisms," reveals Tiphaine Chevallier from the Eco & Sols laboratory. Soil is composedofclay, silt, and sand. But that's not all: it also contains water, air, and... life! Although minerals predominate, organic matter is also part of the composition of this living cocktail commonly known as soil. Organic matter is recycled for plants by countless underground inhabitants (microorganisms, but also microfauna such as protozoa, tardigrades, and mites, and macrofauna such as woodlice, earthworms, and slugs). These organisms ensure the proper functioning of the soil and produce nutrients that are vital for plants: nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. These oases of life are now in danger: every year, ten million hectares of arable land are lost worldwide due to desertification. This threat directly affects the lives of 480 million people.

- A mycorrhiza is the result of a symbiotic association between fungi and plant roots. ↩︎

Find UM podcasts now available on your favorite platform (Spotify, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, etc.).