Innovative drugs: France faces Trump's price war

Faced with Donald Trump's tariffs, French public policy makers are seeking to solve a complex equation. How can public and private organizations be encouraged to develop innovative drugs that meet unmet therapeutic needs, within a constrained budgetary framework, quickly and fairly? Mission impossible?

Augustin Rigollot, University of Montpellier

On May 12, 2025, Donald Trump announces an executive order to lower drug prices in the United States, accusing other countries of taking advantage of overly favorable prices. On August 4, he issues an ultimatum to this effect to 17 major pharmaceutical companies.

This raises fears in France and Europe of an increase in the price of medicines, particularly new molecules that treat unmet therapeutic needs. As the US pharmaceutical market is the largest in the world, a price drop in the world's leading economy will symmetrically lead to price increases in other countries. In the United States, price negotiations mainly take place between laboratories and private insurers, with limited government intervention, resulting in particularly high prices. In Europe, on the other hand, prices are generally lower because they are negotiated by the public payer, with strong government influence. However, the Trump administration wants the United States to systematically benefit from the lowest prices among those observed in other countries. This leaves laboratories with only two choices:

- lowering prices in the United States to the lowest levels, particularly in the European Union (EU), with drug manufacturers then suffering a heavy loss of revenue globally, hampering their ability to invest in innovation;

- increase the price of medicines in EU countries and elsewhere in the world by bringing them closer to US prices, in order to preserve their global margins and limit the decline in their revenues in the United States.

Overall, the countries currently benefiting from the largest discounts will be hardest hit by any increases, and the overall price of therapeutic innovation will rise: a risk to its accessibility.

This news highlights healthcare models around the world, ranging from public insurance funding, as in France, to private insurance funding, as in the United States. So what leverage does France have in the face of rising prices for innovative drugs? What about drugs used to fight cancer (oncology) in particular?

Low drug prices in France

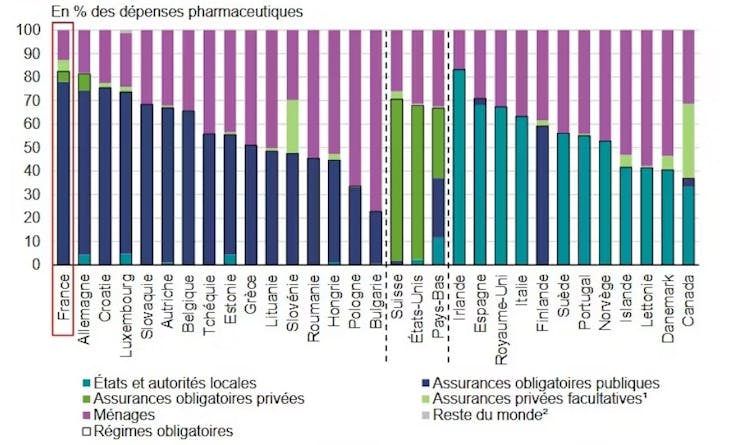

France benefits from effective medical-economic negotiations on drug prices. As a result, drug prices are much lower thanin the US, which makes our country highly vulnerable to potential price increases. There is a historical reason for this: France accounts for a large volume of drug sales in Europe, which are covered by compulsory public insurance. De facto, the market is guaranteed for manufacturers, which is an argument for negotiating lower prices.

France has a restrictive regulatory environment with regard to prices. Low prices in our country mean that out-of-pocket expenses for households are very low, among the lowest in Europe.

However, France is facing growing budgetary constraints, illustrated by the €5 billion in savings planned in the 2026 social accounts. Its room for maneuver in the face of rising innovation costs would therefore be particularly limited.

Accessibility of medicines

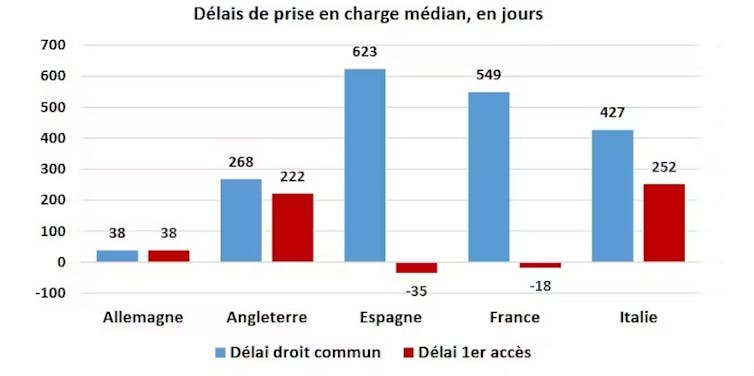

France has less access to pharmaceutical innovation than its European neighbors. 63% of new drugs are available in France, compared to 88% in Germany. For example, in oncology (cancer diagnosis and treatment), France ranks sixth in terms of availability in Europe in 2020. To explain this lack of accessibility, manufacturers point to the shortcomings of the French drug market. Among the barriers to accessibility, the French pharmaceutical industry association (LEEM) highlights the low price of drugs in France, which is not attractive compared to comparable European countries. This lack of attractiveness is not limited to price, and is exacerbated by the long delays in accessing the French market, particularly compared to Germany. This context does not encourage manufacturers to prioritize the French market for their launches.

The early access procedure greatly mitigates this argument regarding access delays.

Thanks to this exceptional procedure, a drug that is considered innovative and meets a major and serious medical need is reimbursed on the market without having to wait for the marketing authorization (MA) procedure to be completed. This has drastically reduced access times for more than 120,000 patients in France, concerning around 100 expensive and innovative molecules, particularly in oncology.

Causes for concern

Another concern, related to solidarity, reflects the expectations of the public payer. It is illustrated by Opinion 135 of the National Consultative Ethics Committee (CCNE) of 2021. The latter is concerned about the sustainability of our social model.

"The very high prices of certain innovative treatments could compromise the financial stability of healthcare systems as they currently operate."

Since this opinion was issued, concerns have grown in parallel with the rise in innovation prices. Now the most expensive drug in the world, Libmeldy (a treatment for metachromatic leukodystrophy) costs €2.5 million for the entire treatment in Europe and approximately $4.25 million in the United States.

Risk sharing agreements

Among the many mechanisms available to us, some allow us to control pricing and market access very early on in negotiations, while supporting effective innovations. This is the case with risk-sharing agreements. These have been documented for around 15 years and are included, for example, in Article 54 of the 2023 Social Security Financing Bill (PLFSS) for innovative therapy medicines (MTI). These agreements between a pharmaceutical company and the public payer aim to limit the financial consequences of new treatments.

These contracts are still rarely used in France. They represent a source of efficiency that public policymakers could leverage in the event of inflation in the price of therapeutic innovation, against the backdrop of a tariff war initiated by Donald Trump's United States.

We distinguish between:

- Purely financial agreements (financial-based agreements), which are the most common. They cap expenditure, with volume thresholds (price-volume agreements) above which the manufacturer reduces its price in order to stabilize the budget. In exchange, the public payer guarantees volumes and better market access.

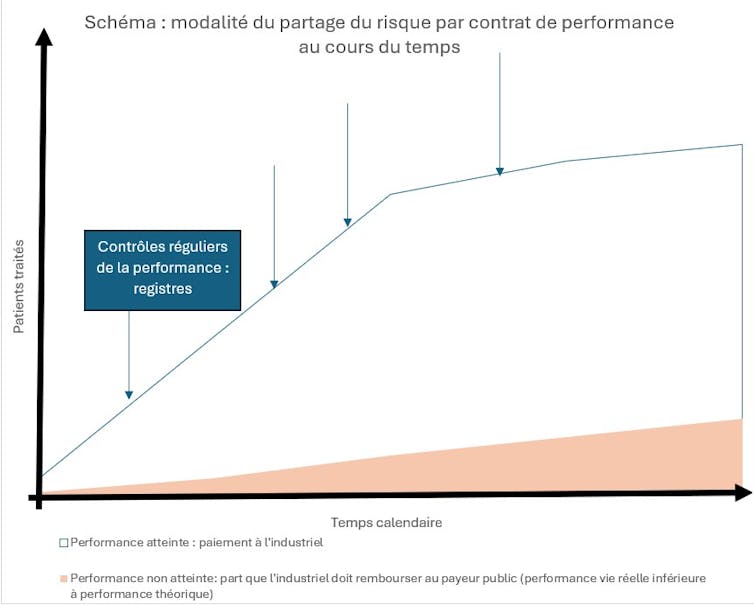

- Performance-based risk sharing agreements that index payment to the actual performance of the drug, rather than solely to the results of clinical trials. They focus on clinical efficiency criteria, with clauses providing for full or partial reimbursement by the manufacturer in the event of insufficient results in real life. These contracts are particularly well suited to drugs with a limited target population (so that real-world performance can be properly monitored), or for which there is a high degree of uncertainty about real-world efficacy at the time of marketing.

The Italian example in oncology

Italy is often considered the most advanced European country in terms of risk-sharing agreements, particularly in oncology. In 2017, the amount saved through these contracts was estimated at nearly half a billion euros (35 million on performance contracts alone). In oncology, the time to market for molecules covered by this scheme is estimated to have been reduced by 256 days.

This rollout in Italy was accompanied early on by a sophisticated system for collecting and evaluating real-life performance data, managed by the Italian Public Health Agency (AIFA). By 2016, it already had 172 real-world data registries covering more than 300 risk-sharing agreements, involving approximately 900,000 patients. The additional cost of this monitoring was estimated at between €30,000 and €60,000 per drug per year in the first year, decreasing thereafter. The question of how this cost is shared between the public payer and the manufacturer must also be taken into account.

This approach to collecting real-life performance data has been lacking in France. This partly explains our lag and the low number of performance contracts—around fifteen in ten years, according to health economist Gérard de Pouvourville.

Today, the challenge remains to develop these contracts without performance monitoring taking up healthcare resources in a context of limited time and medical resources.

Solidarity put to the test

The problem of balancing support for innovation, its accessibility, and the sustainability of the healthcare system is not unique to France. It is such an important issue that it has been included in the Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe in 2020. The European Hi-Prix project is seeking a solution to this problem with the creation of the Pay for Innovation Observatory, which lists all innovation financing mechanisms online.

Faced with the inflation of prices for innovative drugs, which are completely out of step with their sustainability for healthcare systems, an ethical debate is also emerging that cannot be resolved by economic predictions alone.

If the price of innovation, particularly for orphan or rare diseases, continues to rise and if, at the same time, advances in diagnostics, particularly genetic techniques, removeuncertainty about individuals' future health conditions and risks, there is a risk of undermining willingness to pay, which is the basis of the tacit contract of insurance solidarity in our societies.

Augustin Rigollot, graduate of the École Normale Supérieure in economics and philosophy, specializing in health economics (UPEC), sixth-year medical student, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.