Seas of exile: the last refuges for large marine predators

To escape the pressure of human activity, large marine predators have no choice but to seek refuge in isolated reefs and underwater mountains located more than 1,000 km from our coasts.

This is revealed in a major international study published in PLOS Biology, in which David Mouillot, professor at MARBEC, and several PhD students at the University of Montpellier participated.

Sharks, tuna, and swordfish are decreasing in size and number as they get closer to areas of human influence. This is the worrying finding made by researchers from the international PELAGIC project, funded by FRB-CESAB.

Over 1,000 sites observed

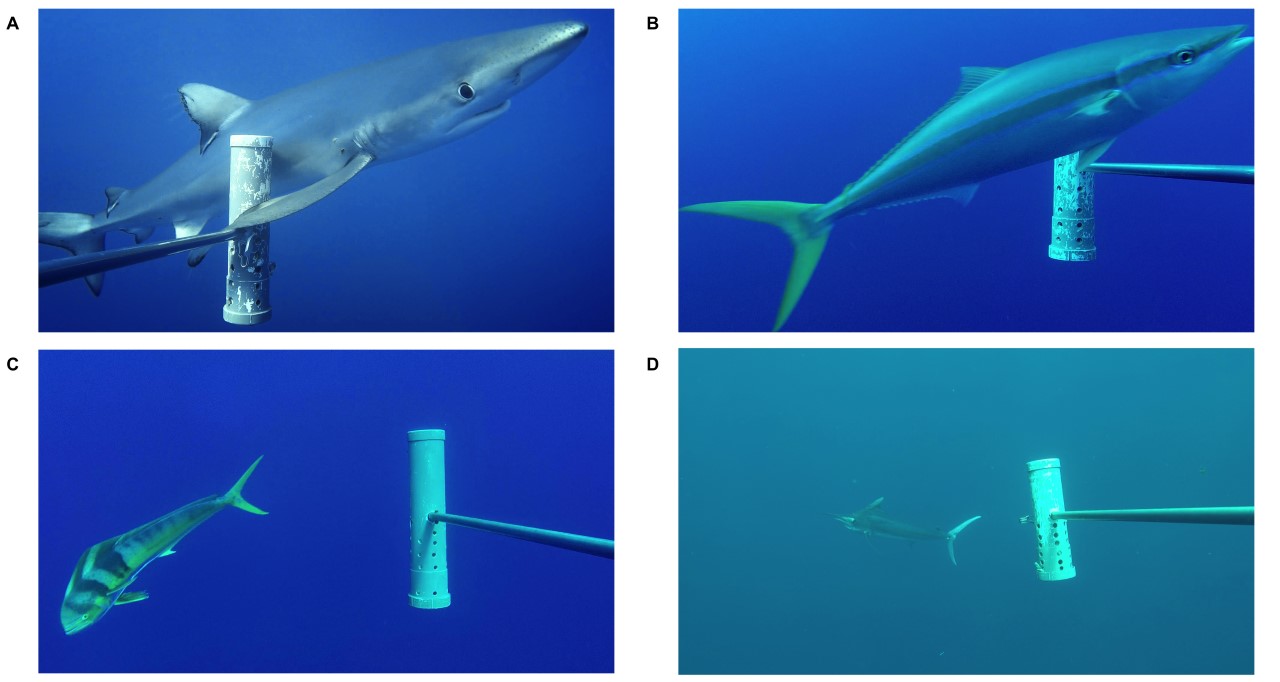

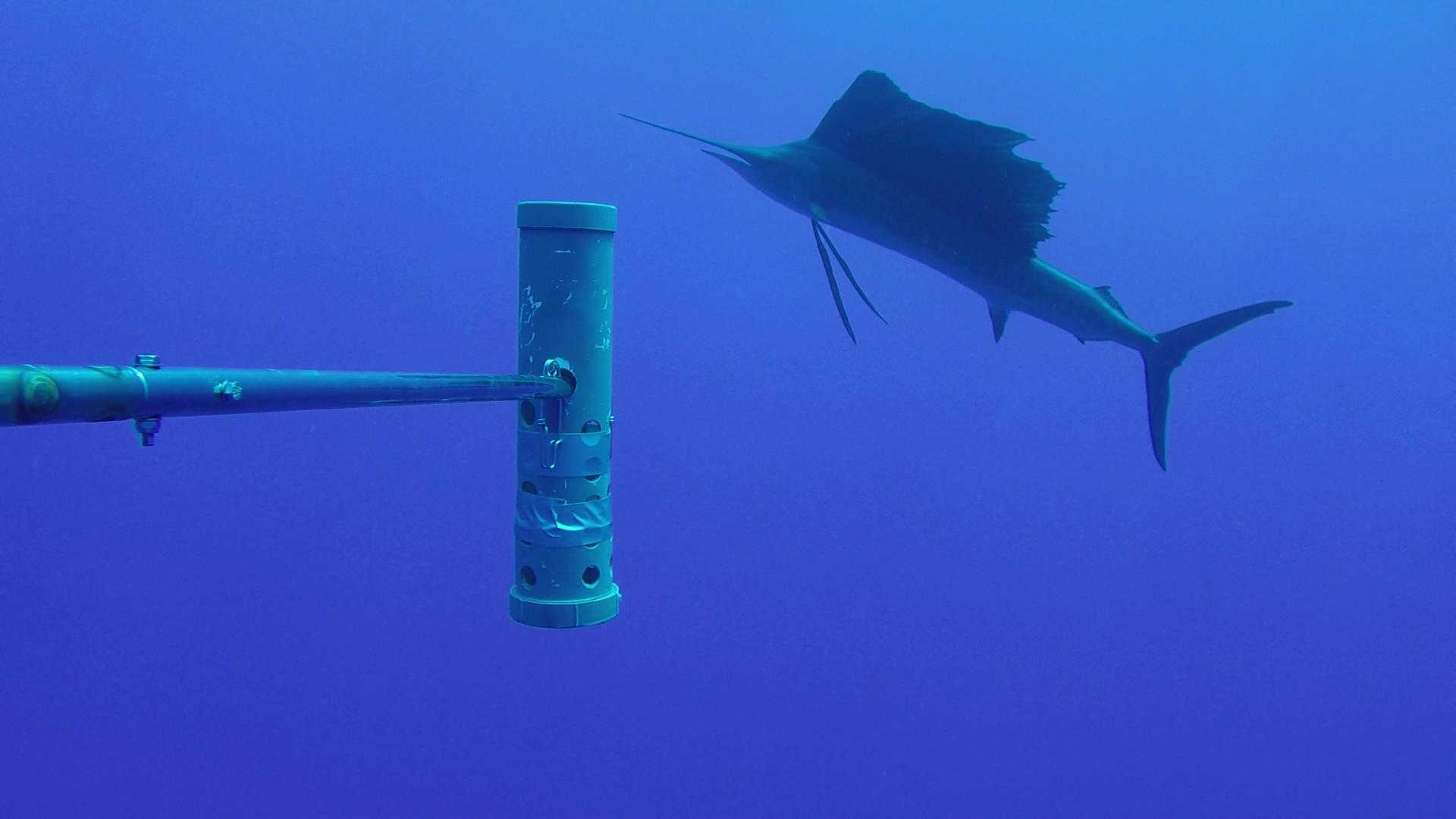

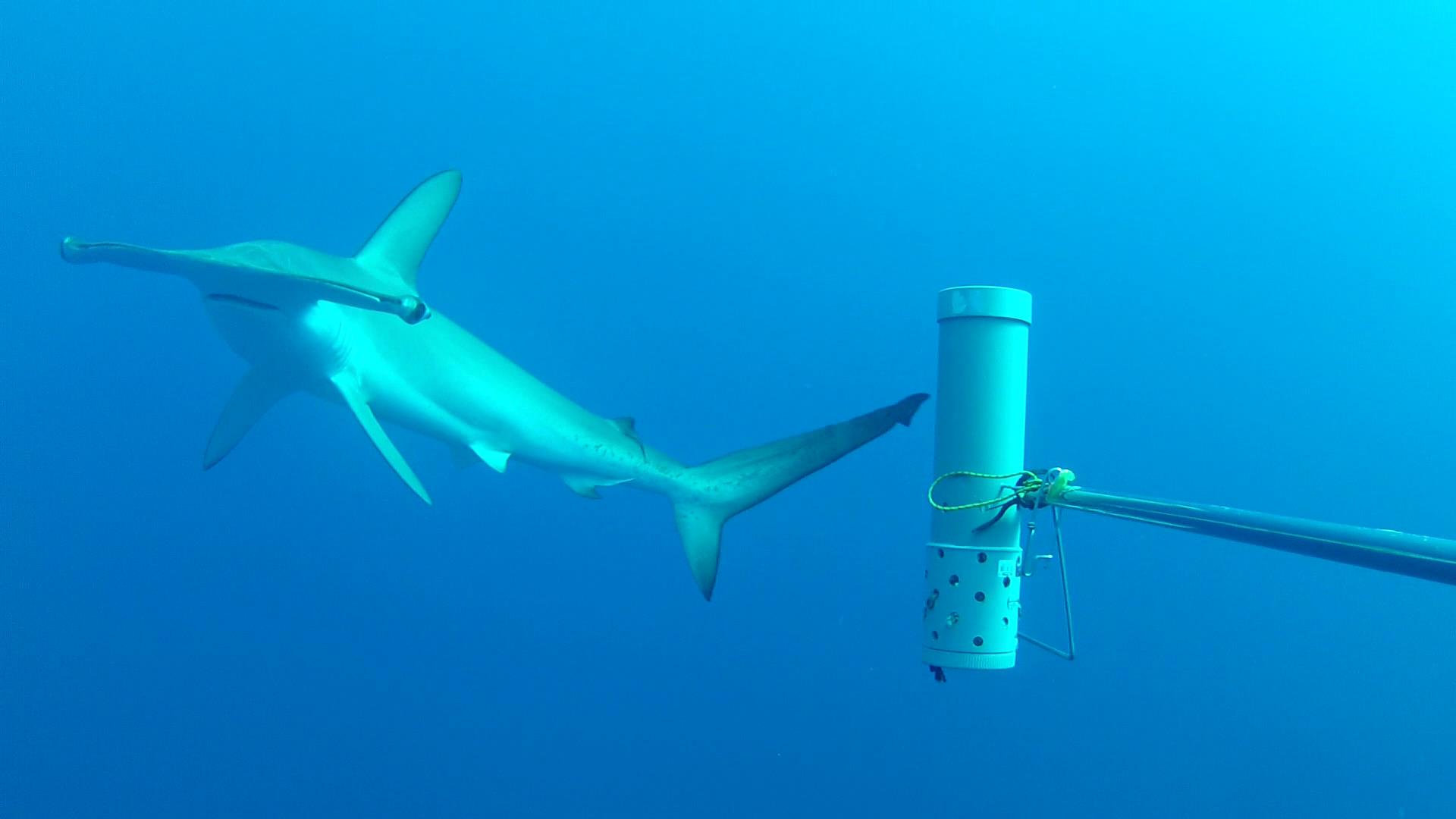

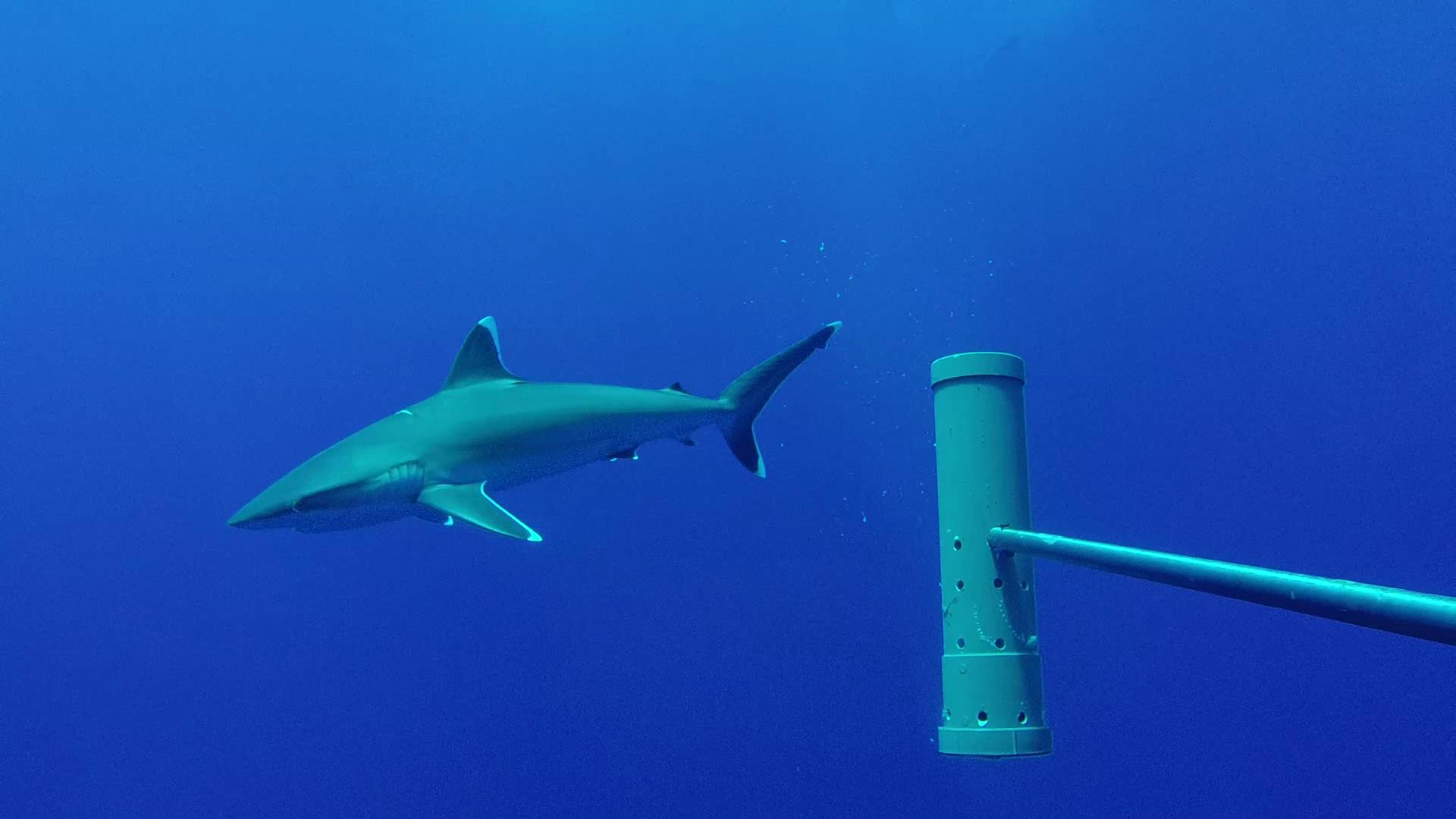

For several years, from 2010 to 2015, the team surveyed more than 1,000 sites in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. At each site, floating stereo cameras equipped with bait—sardines and anchovies, to be precise—were positioned for several hours. The goal? To film and count large predators in each area and assess their size without having to handle or capture them. "This is a world first," says David Mouillot, professor at Marbec. " Never before has a study been conducted on such a large scale based on visual counts. "

The results published in PLOS Biology on August 6 leave no room for doubt. In areas where human pressure is high, particularly due to fishing, the cameras did not record any shark presence. This came as a very unpleasant surprise to the researcher, who did not expect "to find a total absence of these species at nearly 80% of the sites observed."

Critically endangered species

It is more than 1,250 km from ports, in isolated reefs or underwater mountains, that researchers have been able to observe a real concentration of these species (more than twenty individuals in a single image) and glimpse large specimens (>5 m). "They are gathering in the last remaining refuges, but their survival is now extremely threatened," warns David Mouillot. "It is much more difficult to prove extinction phenomena at sea than on land. We have only been interested in this for the last ten years or so."

The only good news is that biodiversity, or species diversity, does not seem to be affected by human activities. How long before humans reach these last refuges? "A thousand kilometers from humans is surely the threshold beyond which certain boats will not go because fishing is no longer profitable, mainly due to the cost of fuel ," explains David Mouillot, who warns of the consequences that a drop in fuel prices or subsidies to offset this price could have, as it certainly acts as a barrier to the overexploitation of certain areas of the ocean.

Shifting political boundaries with science

Since the 1950s, industrial fishing has quadrupled in volume , rising from 20 million tons to 80 million. In total, 55% of the oceans are exploited by fishing, while marine protected areas represent only 3.4% of the ocean's surface.

These protected areas ultimately cover very little of the preferred habitats of marine predators, as the researcher already pointed out in a previous publication (see our article Too Close to Humans in LUM No. 8). Hence the importance of establishing new marine protected areas as quickly as possible, including areas of the high seas far from all human activity.

This is a priority according to David Mouillot, for whom "publishing in journals is not an end in itself. We want to bring about change at the legislative and political level by sending out simple messages. We need to make leaders aware of the rarity and importance of our last remaining refuge ecosystems in this new Anthropocene era." Awareness-raising through research has already led to the protection of the Chesterfield Islands off the coast of New Caledonia, thanks to previous expeditions.

Drones and environmental DNA

The international team is currently continuing this study at more than 3,000 sites. The Mediterranean is now part of their monitoring areas. In addition to bait cameras, researchers are now working with environmental DNA with SpyGen, a company that recently set up at MARBEC through the iSite MUSE Companies on Campus initiative. "These techniques make it possible to detect the presence of predators in addition to the installation of cameras, thanks to the DNA traces they leave in the water. This opens up a much wider spatial and temporal window of detection. Here too, we have the ambition of global coverage of the oceans with a biodiversity observatory via eDNA (ALIVe: All Life InVentory using eDNA), which has just been certified by ADEME with SpyGen as the lead partner."

Identifying megafauna using drones and microlights in coastal areas will further enrich this study. A postdoctoral researcher from MARBEC, who has just been awarded a European Marie Curie grant with the University of Montpellier, will be working on this project in the lagoon of New Caledonia in collaboration with the ENTROPIE laboratory. New techniques to "ensure a new generation of monitoring for this megafauna, which is a real conservation challenge," concludes David Mouillot. "These species will be the first to disappear from our oceans."

On Friday, November 29, 2019, CESAB (Center for Synthesis and Analysis on Biodiversity), a flagship program of the Foundation for Research Biodiversity (FRB), which is funding the Pelagic project and working group, is organizing a conference on this topic in Montpellier. The conference will address new challenges in monitoring wildlife and human activities in protected areas.

- Registration required at http://www.fondationbiodiversite.fr/