Seas of exile: the last refuges of large marine predators

To escape the pressure of human activity, large marine predators have no choice but to exile themselves to isolated reefs and seamounts over 1000 km from our coasts.

These are the findings of a major international study published in PLOS Biology, in which David Mouillot, a professor at MARBEC, and several PhD students at the University of Montpellier took part.

Sharks, tunas and swordfish are decreasing in size and numbers the closer they get to areas of human influence. These are the worrying findings of researchers working on the international PELAGIC project, funded by FRB-CESAB.

More than 1,000 sites observed

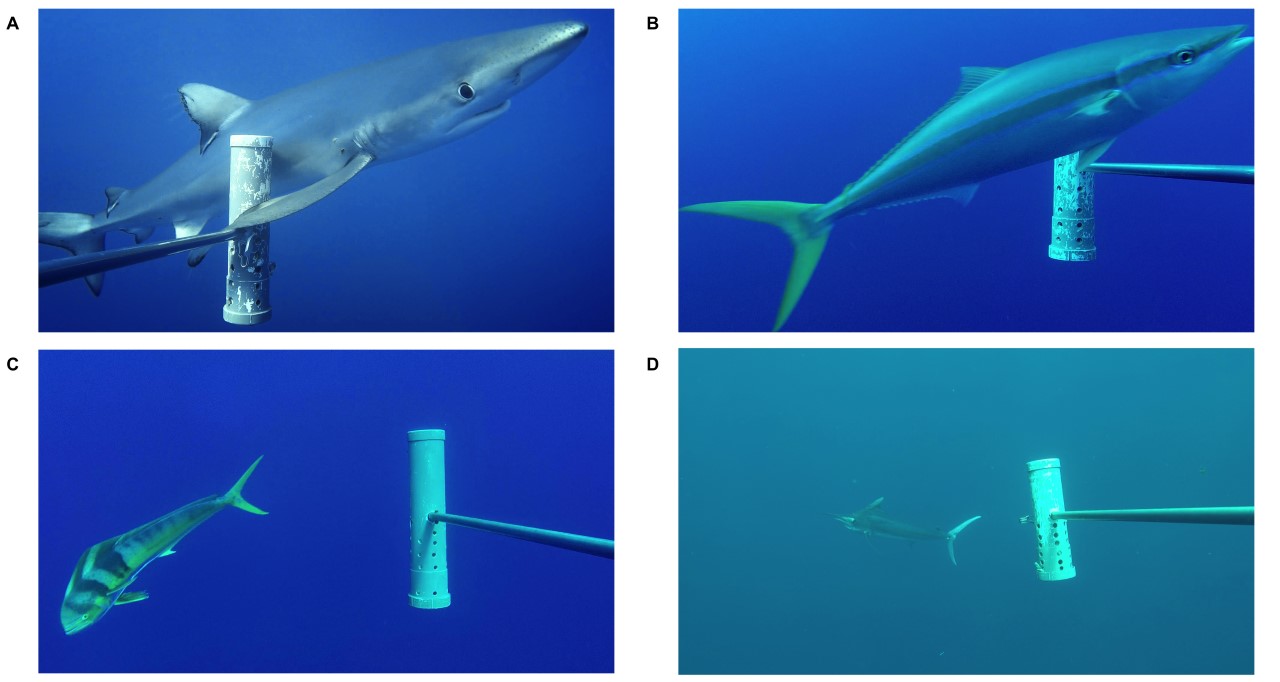

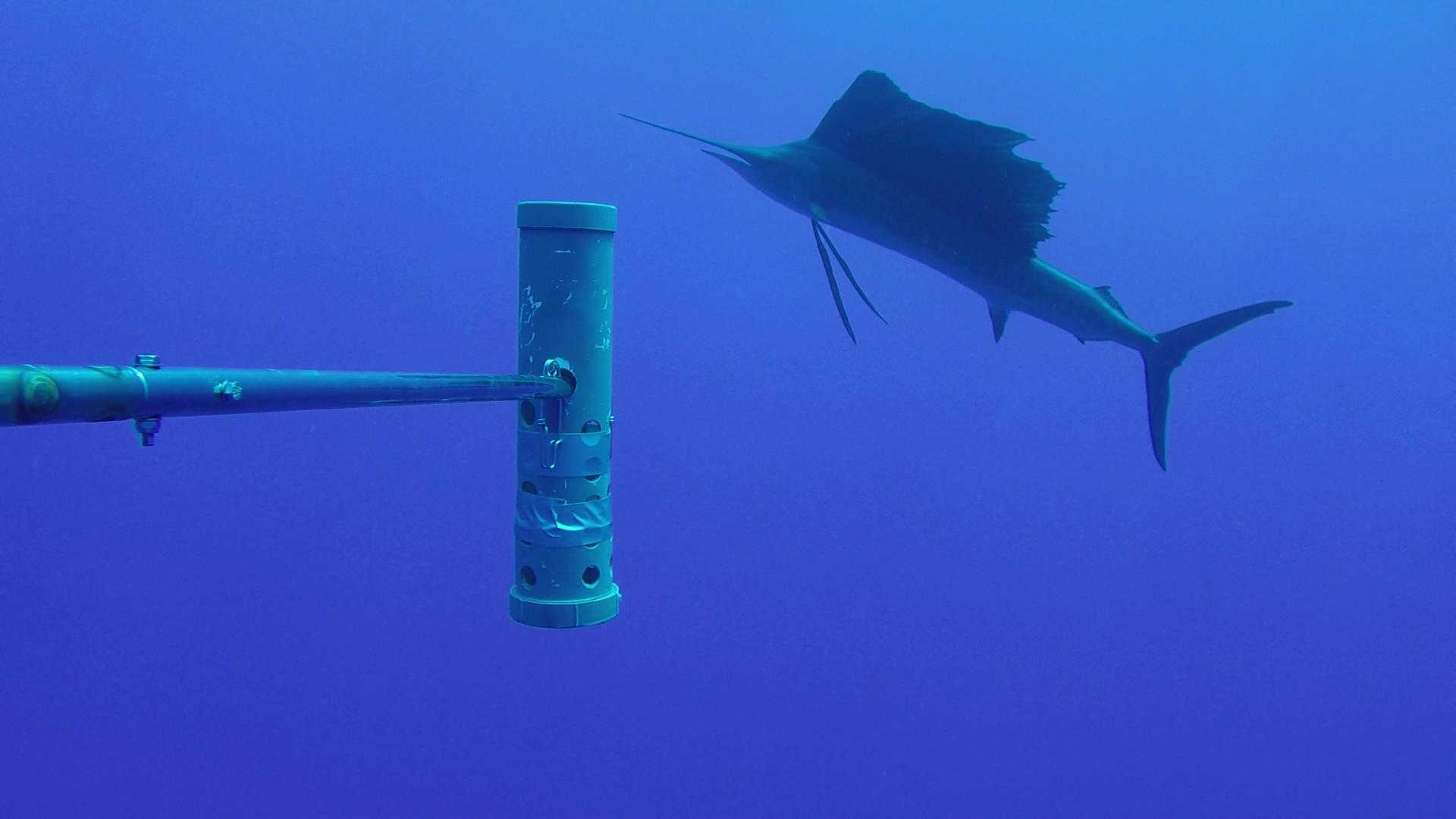

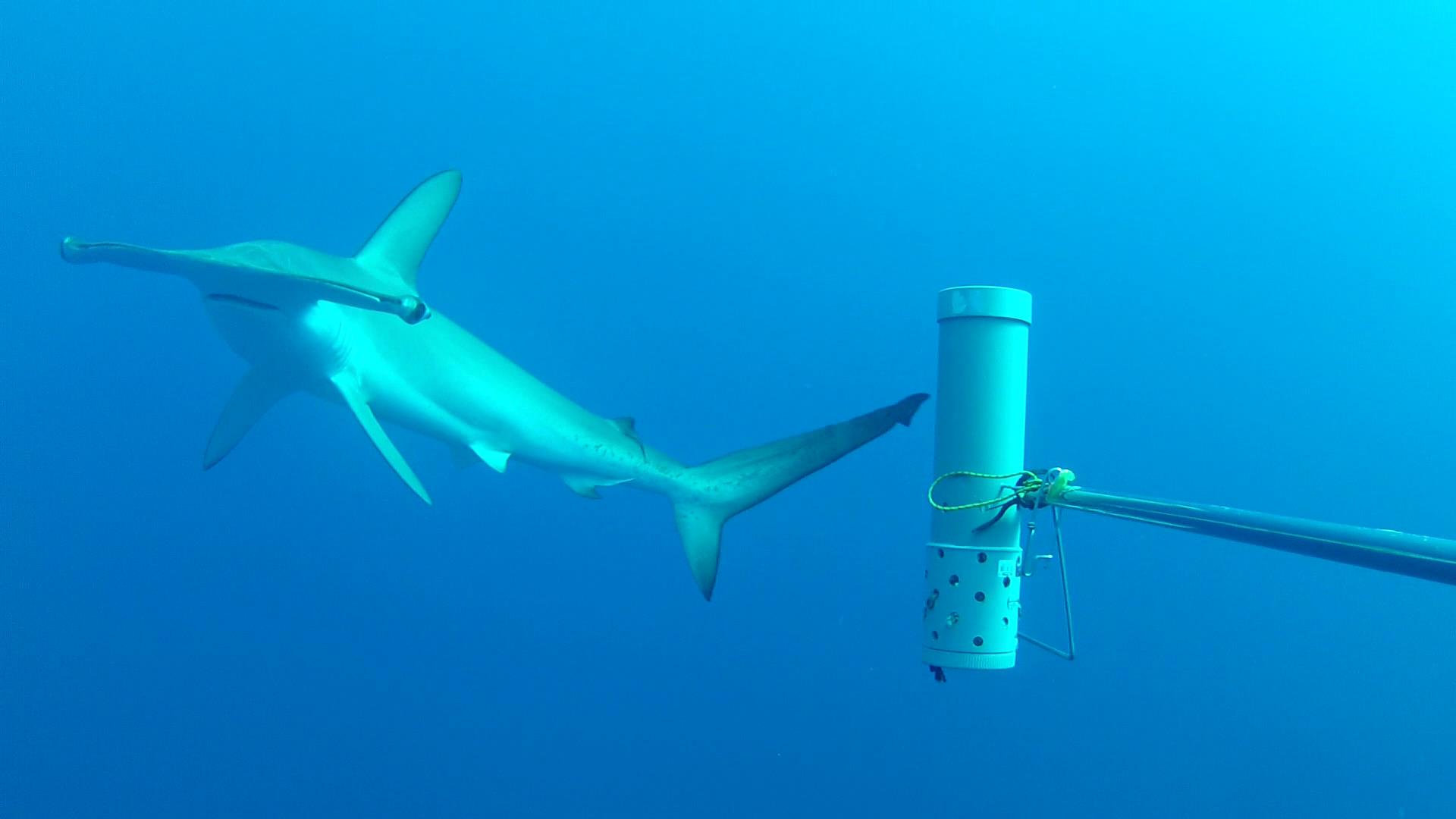

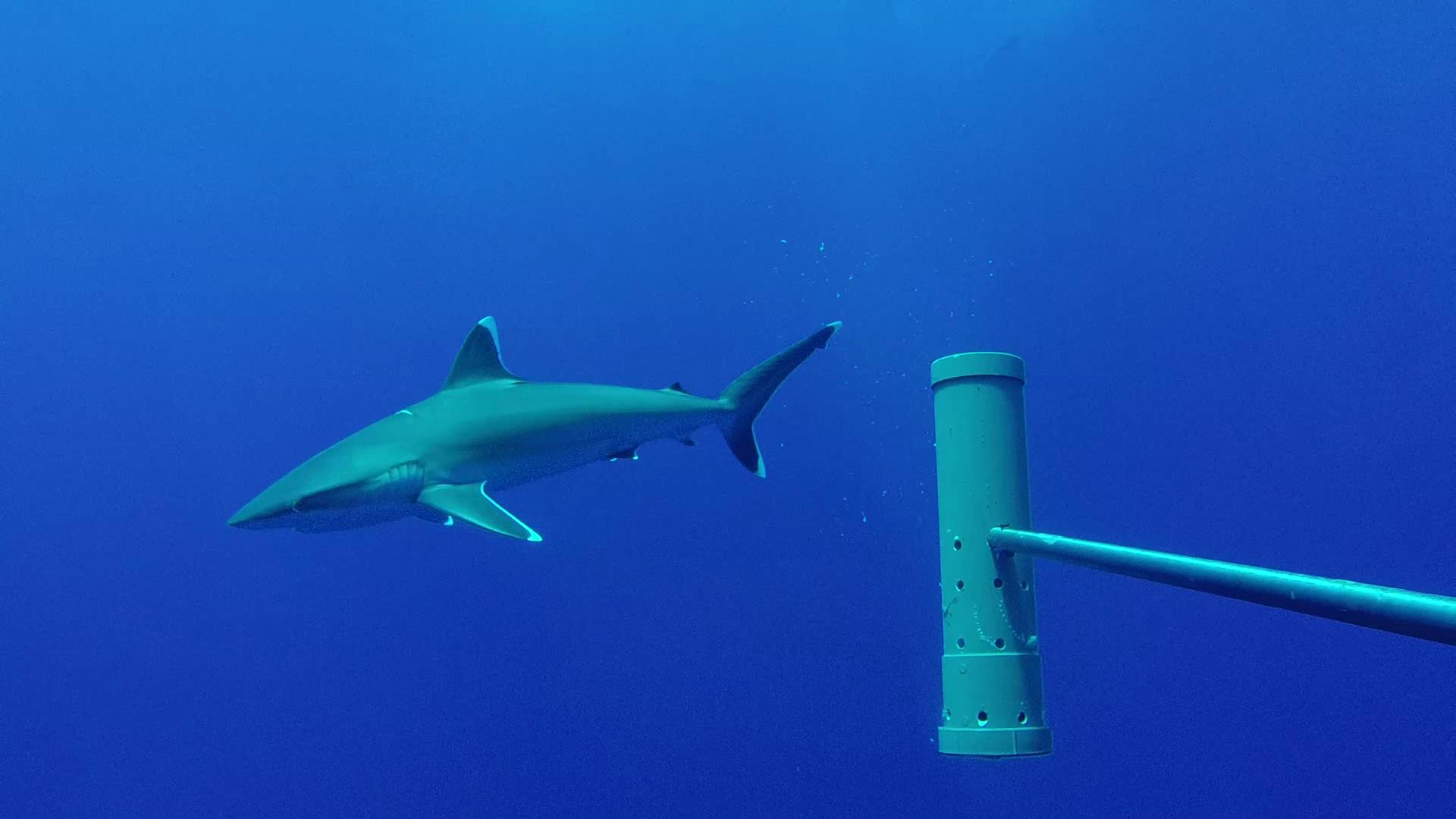

Over several years, from 2010 to 2015, the team surveyed more than 1,000 sites in the Indian and Pacific oceans. At each site, floating stereo cameras equipped with bait - sardines and anchovies to be precise - were positioned for several hours. The objective? To film and count the large predators in each area and assess their size without having to handle or capture them. A world first," says David Mouillot, a professor at Marbec, " never before has a study been carried out on such a large scale using visual censuses.

The results published in PLOS Biology on August 6 leave no room for doubt. In areas where anthropic pressure is high, notably due to fishing, the cameras did not record the slightest presence of sharks. A very unpleasant surprise for the researcher, who had not expected "to observe a total absence of these species in almost 80% of the sites observed".

Extremely threatened species

It was more than 1,250 km from ports, on isolated reefs or seamounts, that researchers were able to begin observing a real concentration of these species (more than twenty individuals in a single image) and glimpses of large specimens (>5m). They are accumulating in the last refuges they have left, but their survival is now extremely threatened," warns David Mouillot. It's much harder to prove extinction phenomena at sea than on land. We've only been looking at it for the last ten years or so."

The only good news is that species richness, in other words, diversity, does not seem to be affected by human activity. How long before man reaches these last refuges? " A thousand kilometers from man is probably the threshold beyond which some boats won't go, because fishing is no longer profitable, notably due to the cost of fuel," explains David Mouillot, who warns of the consequences of a drop in fuel prices or subsidies to compensate for this price, which surely acts as a barrier to the over-exploitation of certain areas of the ocean.

Moving political lines with science

Since the 1950s, the volume of industrial fishing has quadrupled from 20 million tonnes to 80 million. In total, 55% of the oceans are exploited by fishing, while marine protected areas represent only 3.4% of the ocean's surface.

Protected areas which, in the end, barely cover the preferred habitats of marine predators, as the researcher has already pointed out in a previous publication(see our article Trop proche humain in LUM no. 8). Hence the importance of establishing new marine protected areas as soon as possible, including deep-sea zones far removed from all human activity.

A priority for David Mouillot, for whom " publication in journals is not an end in itself. We want to move the legislative and political yardsticks by raising awareness with simple messages. We need to make leaders aware of the scarcity and importance of our last refuge ecosystems in this new era of the Anthropocene." Raising awareness through research has already led to the protection of the Chesterfield Islands off the coast of New Caledonia with previous expeditions.

Drones and environmental DNA

The international team is currently pursuing this study at over 3,000 sites. The Mediterranean is now one of their monitoring zones. In addition to baited cameras, the researchers are now working with environmental DNA in collaboration with SpyGen, a company recently set up at MARBEC via the Companies on Campus initiative of the MUSE iSite. " These techniques enable us to detect the presence of predators in addition to installing cameras, thanks to the DNA traces they leave in the water. This opens up a much wider spatial and temporal window of detection. Here too, our ambition is to provide global coverage of the oceans, with a biodiversity observatory using eDNA (ALIVe: All Life InVentory using eDNA), which has just been accredited by ADEME, with SpyGen as the initiator."

Identification of the megafauna using drones and microlights in coastal areas will further enrich this study. A post-doctoraldoctoral student from MARBEC, who has just been awarded a European Marie Curie scholarship with the University of Montpellier, will be working on this project in the lagoon of New Caledonia, in collaboration with the ENTROPIE laboratory. New techniques to " ensure a new generation of monitoring of this megafauna, which is a real conservation issue", concludes David Mouillot. These species will be the first to disappear from our oceans."

On Friday November 29, 2019, the CESAB (CEntre de Synthèse et d'Analyse sur la Biodiversité) flagship program of the Fondation pour la Research sur la Biodiversité (FRB), which is funding the project and the Pelagic working group, is organizing a conference on this subject in Montpellier. It will discuss the new challenges of monitoring wildlife and human activities in protected areas.

- Registration required on http://www.fondationbiodiversite.fr/