Why it is unlikely that the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus will lose its virulence

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, strong opinions have regularly been expressed about the evolution of SARS-CoV-2's virulence. Many believe that it is bound to decrease, since viruses, bacteria, and other parasites have "always" lost their virulence by adapting to their hosts.

Samuel Alizon, Research Institute for Development (IRD) and Mircea T. Sofonea, University of Montpellier

Unfortunately, this "intuition" does not stand up to analysis, as it requires us to view the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the tuberculosis bacillus, the malaria parasite, and even the flu as exceptions. In fact, no matter how hard we look, it is difficult to find "parasites" (to use a term from evolutionary biology) that conform to this axiom, dubbed the "law of decreasing virulence" at the beginning of the 20th century.

Why then does this view persist? What do recent discoveries in evolutionary biology teach us about virulence? And what can we expect in the case of SARS-CoV-2?

Do not confuse lethality with virulence.

The logic behind the theory of a systematic evolution of parasites towards anon-virulent state is childishly simple: for the parasite, killing its host is like killing the goose that lays the golden eggs. In other words, strains (or "variants," to use a more fashionable term) that kill their host quickly should be less successful than others and therefore disappear.

One explanation for why this century-old theory is still so prevalent is the confusion between the concepts of lethality and virulence.

Lethality is the proportion of infected individuals who die as a result of infection by a given parasite, in a given place, at a given time. Many factors contribute to reducing apparent lethality: treatments, vaccination, quality of clinical care, etc. Virulence, on the other hand, corresponds to the parasite's propensity to harm its host. It is quantified in the absence of specific care.

In other words, the same viral variant will have a different lethality from one country to another depending, for example, on the quality of the hospital system. However, its virulence will remain unchanged.

In the case of SARS-CoV-2, there has been a decline in lethality since the start of the epidemic in many countries, largely thanks to vaccination. However, virulence has increased. Infections with the Alpha variant are more likely to cause death than those involving the ancestral lineages that were circulating in early 2020. As for the Delta variant, initial results seem to indicate that it is more virulent than the Alpha variant, as it leads to more hospitalizations among unvaccinated people. Preliminary results point in the same direction for the Beta variant.

Let's admit that this is counterintuitive. But it also illustrates that evolutionary biology is a discipline in its own right, and that it is risky to proclaim oneself an expert in it. However, many consider it more of a "hobby" that one might pursue after gaining sufficient experience in more related subjects, such as the mechanisms of development or the physiology of organisms. This is probably another reason for the persistence of misconceptions about the evolution of virulence.

Does evolutionary biology really have more to offer than the insights of "wise elders"? Obviously, this field of research suffers from the fact that it is impossible to reproduce an epidemic identically. However, the analysis of epidemics prior to the one we are currently experiencing (notably HIV) and so-called "experimental" evolutionary studies conducted on other parasites are rich in lessons.

Two types of virulence

To begin with, we must distinguish between two categories of damage inflicted by a parasite on its host, depending on whether or not they influence the spread of the parasite: non-adaptive virulence and adaptive virulence.

Non-adaptive virulence does not benefit either party. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, this includes particularly severe manifestations of the infection, such as cytokine storms. The second category of virulence is known as "adaptive" because it is associated with improved spread of the parasite, either directly or indirectly.

Seth Pincus, Elizabeth Fischer, and Austin Athman, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH

In the case of HIV, for example, it has been shown that more virulent variants—those that produce more viral particles by exploiting their host cells more efficiently or evading the immune response more effectively—are also more contagious, as the probability of transmission is linked to the amount of virus in the blood.

Distinguishing between non-adaptive and adaptive components of virulence allows us to better understand the evolution of this trait. We generally expect non-adaptive virulence to decrease, since it is only associated with costs. However, it is not that simple, because we must take into account the parasite's life cycle.

In the case of SARS-CoV-2, severe symptoms generally appear two weeks after infection, yet more than 95% of transmissions occur before the11th day. In other words, from the perspective of this coronavirus, late pathological manifestations (particularly inflammatory ones) of virulence do not constitute a loss of transmission opportunities. Consequently, it is unfortunately unlikely that natural selection will favor variants that cause such immunopathological manifestations less often.

When it comes to the adaptive component of virulence, predictions are even less straightforward. Everything depends on the relationship between costs (virulence) and benefits for the spread of the virus (transmission rate, duration of infection). In the case of HIV, again, it has been shown that an intermediate level of virulence maximizes the selective value of the virus, i.e., the number of infections caused by a person carrying the virus.

One factor that could lead us to believe that such a correlation between virulence and transmission exists in the case of SARS-CoV-2 is that the more transmissible variants are also more virulent.

For example, our team showed that in France, the Alpha variant had a clear advantage in terms of transmission compared to ancestral lineages. Our British colleagues concluded that its virulence had increased by 50%. Similarly, in June 2021, we showed that the Delta variant was more contagious than the Alpha variant. According to this logic, a more transmissible variant could therefore be even more virulent.

What can we expect?

The fact that more contagious variants are more virulent suggests that the adaptive component of virulence is not zero.

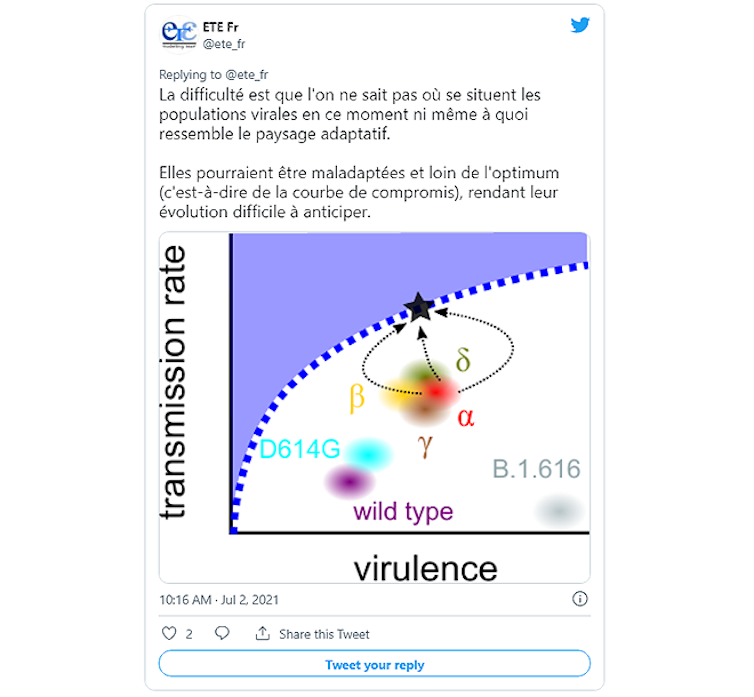

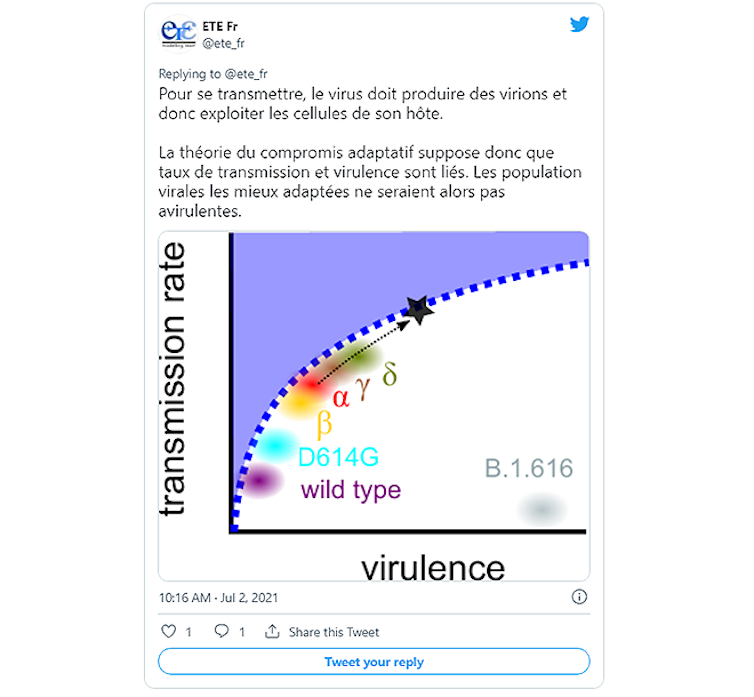

The difficulty in anticipating viral evolution is that we need to know how well the virus, i.e., the Delta variant, has now adapted to us. Does this coronavirus still have room to exploit its human host more effectively (in other words, could it be less virulent for this level of contagiousness)? Or, on the contrary, would any decrease in virulence also result in a decrease in contagiousness?

@ete_fr – July 2, 2021

In the first case, while the virus retains some leeway to better adapt to its host, it is virtually impossible to anticipate the next stage in its evolution. Mutagenesis experiments could nevertheless help to identify the most stable viral forms. It should be noted that these generations of mutants are produced in the laboratory in a safe manner (for example, only a given viral protein is worked on).

This type of work, known as "deep mutation screening," was carried out on a section of the gene used to produce the virus's S protein (the one containing information about the part of the protein called the receptor binding domain, or RBD), which acts as a "key" to enter our cells. It involves generating all possible mutations in the RBD and then studying their effect on the production of the resulting S proteins and their ability to bind to the ACE2 receptor located on the surface of cells (the receptor that serves as the entry point for the virus). This work has identified sites that are particularly at risk in terms of the evolution of variants.

@ete_fr – July 2, 2021

In the second case, we might expect virulence to stabilize around a value that maximizes the number of secondary infections, thus optimizing the balance between transmission rate and virulence. Predicting this would require knowing exactly the constraints between these two characteristics of the infection. But, again, that's not the end of the story.

The effects of immunization

Immunization of populations (natural or through vaccination) disrupts the adaptive landscape of viruses: the most adapted variant in an unprotected population may find itself in the minority in an immunized population. Brazil experienced this in a tragic way, as it built herd immunity at the cost of a major health disaster, yet still fell victim to a second wave due to the Gamma variant—which is thought to have rapidly invaded the country because it was partially able to evade the immunity conferred by ancestral strains.

NIAID/NIH

In the short term, vaccination is essential: like natural immunity, it reduces the lethality of the infection, accelerating the transition to a dynamic similar to that of seasonal respiratory viruses. Indeed, a year ago, no one would have dared to hope for such vaccine efficacy against severe forms of the disease (even for the Delta variant, this protection is estimated to be around 85%). This effectiveness highlights vaccine inequalities even more: for those who will not have the chance to access the vaccine, the lethality of infections is already higher than in 2020 and could increase further with the evolution of future variants.

Reconciling Pasteur and Darwin

Beyond the sense of urgency resulting from the health situation, it is important to consider the pandemic in the medium and long term. Forecasts are very difficult to make, because the relationship between the virus and our immune system is co-evolutionary: viruses mutate and our immune responses change. In order to try to anticipate the future, we must take into account the effectiveness and duration of natural and vaccine-induced immunity, which slow down the rate of evolution of viral populations: fewer infections means fewer mutations...

The study of these dynamic relationships and their implications is the subject of evolutionary biology. Unfortunately, in addition to the chronic lack of funding for scientific research in France, this discipline suffers from a lack of recognition and the available knowledge is too rarely put to good use. One example among many: despite efforts to include various aspects of SARS-CoV-2 research within the scientific council, there are no evolutionary biologists among its members.

Relying on the intuitions of "traditional wisdom" to anticipate evolving trends in pathogens, while ignoring the latest discoveries and tools in evolutionary biology, is like walking blindfolded. When it comes to infectious diseases, this can have particularly serious consequences given the speed at which microbes evolve and spread. In public health, there is an urgent need to reconcile Louis Pasteur and Charles Darwin.

For more information:

– Alizon, S. & Sofonea, M. T. (2021) SARS-CoV-2 virulence evolution: Avirulence theory, immunity, and trade-offs. Journal of Evolutionary Biology

– Alizon S. (2020) Pandemics, Ecology, and Evolution, Points Publishing![]()

Samuel Alizon, Director of Research the CNRS, Research Institute for Development (IRD) and Mircea T. Sofonea, Senior Lecturer in Epidemiology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases, MIVEGEC Laboratory, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.