What kind of school in a world that is overheating?

In a rapidly urbanizing world, where young people are spending less and less time outdoors, the benefits of connecting children with nature are now the subject of extensive research and are increasingly well documented.

Sylvain Wagnon, University of Montpellier

Outdoor activities appear to be beneficial not only for young people's health, but also for their overall well-being. Playing and spending time in nature—observing, running, singing, listening, and smelling—also promotes a different relationship with oneself and the environment.

Nature experiences and child development

Even before considering the benefits of exposure to nature for the development of future citizens in the context of global warming, time spent outdoors promotes children's physical and mental health. For example, a causal link has been established between time spent outdoors and the prevention of myopia.

In 2008, orthoptics professor Kathryn Rose assessed the average time spent outdoors by a cohort of Australian children (two hours on average) and then Singaporean children (only 30 minutes on average) in order to correlate this exposure to natural sunlight with myopia, which is twice as high among young Singaporeans.

In recent years, scientific research has also enabled us to link reduced access to natural spaces with allergy risk and predisposition toobesity.

Eight proven benefits of nature on learning

Research, notably that conducted by Ming Kuo, professor of environmental science at the University of Illinois, also highlights the benefits of proximity to nature for academic success and the development of future citizens who are responsible and committed to preserving our planet.

In a meta-analysis published in 2019, Ming Kuo and his colleagues reviewed various studies on the potentially positive roles of nature in child development.

They identified eight benefits: exposure to nature improves attention, self-discipline, interest, physical fitness, reduces stress, and creates a calmer environment conducive to both greater cooperation and autonomy. The study emphasizes that these benefits were observed even when exposure was limited.

[More than 85,000 readers trust The Conversation's newsletters to help them better understand the world's major issues. Subscribe today]

Published in 2016, studies show, for example, that students randomly assigned to classrooms with a view of greenery perform better on concentration tests and experience a decrease in heart rate and stress levels.

School outside, an ancient story

As soon as industrial and urban society emerged inthe 19th century, educational reformers, particularly those involved in progressive education, had already highlighted the need to connect with nature.

At the beginning of the20th century, Belgian educator Ovide Decroly also affirmed this with a striking statement:

"Class is when it rains."

During the same period, Élise and Célestin Freinet proposed the concept of the "class walk," an educational activity that involves taking students outside the classroom to explore nature, observe, collect data, and experiment directly, thereby integrating learning through concrete interactions with the environment. For example, during a walking class, students can study the different types of trees in a park, observe local wildlife, and document their discoveries through drawings or descriptions.

A global dynamic

The benefits of an education that is closer to nature and more aware of climate issues have also been attracting the interest of leaders for several decades.

As early as 1975, UNESCO's Belgrade Charter declared that a new type of education was needed in order to:

"To develop a global citizenry that is aware of and concerned about the environment and related issues, a citizenry that has the knowledge, skills, attitudes, motivation, and commitment to work individually and collectively to solve current problems and prevent new ones from arising."

Nearly fifty years later, in September 2022, the UN Summit on Transforming Education reaffirmed the crucial role of education in the era of climate change, proposing the establishment of a "partnership for green education."

Seeking both to reform the education framework (with "green, sustainably operated schools") and to achieve its ambition of introducing "green programs incorporating climate education" into classrooms through adequate teacher training, the stated goal of this partnership is to double the number of countries that include climate education in school curricula at the pre-primary, primary, and secondary levels.

Highly disparate implementations

For the moment, however, the situation remains very uneven from one country to another. UNESCO has found that more than half of school curricula around the world make no reference to climate change, and only 19% mention biodiversity.

In recent years, however, political choices in line with UNESCO's objectives have been observed. In 2019, Italy became the first country in the world to incorporate global warming into the compulsory core curriculum of its education system, with 33 hours of specific teaching.

Starting in 2020, Cambodia is following suit by including global warming and its study in high school curricula and developing a network of pilot schools engaged in climate-resilient agriculture projects.

In 2021, the Argentine parliament ratified a law requiring environmental education to be included throughout all stages of the school curriculum.

But such changes are not always permanent. For example, although India has long been a pioneer in this area, with its Supreme Court ruling in 2004 to make environmental studies a compulsory subject at all levels of the curriculum, the country has recently backtracked by removing the chapters on global warming from the syllabus.

PISA assessments

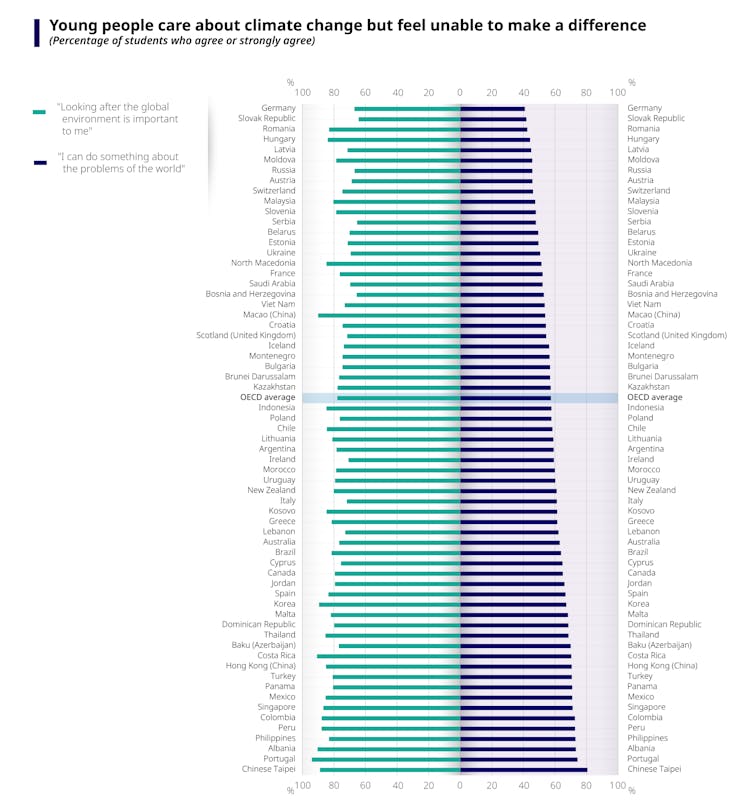

Since 2006, PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) has been assessing children's environmental knowledge around the world. Report after report, the data collected confirms the disparities lamented by UNESCO... and points to others.

Data collected in 2018 shows that while 79% of children in the 38 OECD countries say they are aware of global warming, this figure rises to 90% in Hong Kong and falls to 40% in Saudi Arabia.

That same year, PISA also asked students whether they felt hopeful that they could "do something to solve these global problems." Fifty-seven percent answered yes. Surprisingly, the report continues, this figure is not correlated with the knowledge acquired: in the two highest-performing OECD countries—Korea and Singapore—only 20% and 24% of students surveyed believe they can have an impact on climate change.

Age and gender dimensions

Within the same country, awareness of global warming and the desire to take action to combat this global problem can also vary significantly depending on age and gender.

In Australia, for example, a team of researchers from the University of Sydney surveyed 1,000 urban students aged 8 to 14 and found that while one in two children said they felt "strongly connected to nature" and were therefore inclined to engage in activities to protect biodiversity, this figure fell to one in five by the time they reached adolescence.

Another difference pointed out by researchers is that girls show more empathy toward wildlife and, on average, have formed closer emotional bonds with plants than boys.

Eco-delegates in French middle schools and high schools

In France, Article 5 of the Climate and Resilience Act of August 2021 enshrines the fundamental role of education for sustainable development for all, from primary school to high school. This ambition is also present at the European level: since 2022, a new skills framework, GreenComp, has been put in place to offer a new approach that "encompasses and transcends simple environmental preservation by reexamining the place of human beings and the meaning to be given to the development of our societies."

During Emmanuel Macron's first five-year term, French middle and high schools will have seen the arrival of an eco-delegate in each class, responsible for raising awareness of climate issues among their classmates. With the new 2019 curricula, the terms "global warming (or climate change)" have also been included in high school science and Earth science programs.

At the time, several voices in the research community, including Valérie Masson-Delmotte, climatologist and chair of IPCC Working Group I, considered this development to be lacking in ambition.

Since then, several initiatives have been launched to strengthen the tools and resources needed to bring education in line with climate challenges.

In March 2023, the report by the General Inspectorate of National Education—entitled "How can education and research systems be both transformed and transformative in the face of climate change?"—listed nine recommendations, emphasizing in particular the training of teachers "in the impacts of human activities on the environment and knowledge of the international context," the implementation of "measures to assess the environmental impact of schools," the "strengthening of science education" in primary schools, and the implementation of "educational projects related to environmental issues" with a "dedicated interdisciplinary slot."

In the same vein, on June 23, 2023, the Ministry of Education announced 20 measures designed to give students a better understanding of the challenges of ecological transition in the context of their education.

Which subjects are involved in environmental education?

On a global scale, the question of which subjects should be involved in environmental education is increasingly debated. Often confined to science classes, some believe that the study of climate challenges should also be included in other subjects.

Amanda Power, a historian at Oxford University, suggests, as she pointed out in an article published in The Conversation UK in 2020, that history curricula should be updated to educate students about the origins of the climate crisis:

" One of the main problems with the public's understanding of the current situation is that most of the information and interpretations come from science. Scientists can explain what is happening and make projections for the future. Knowing why human societies have made the choices that have led us to where we are today is not part of their discipline. Yet contemporary climate and environmental crises are the result of human activity."

Similarly, Nigerian professor of philosophy of education Bellarmine Nneji strongly advocates for integrating environmental ethics into school curricula in order to prepare students for climate issues from an early age. In an article published in 2022 on The Conversation Africa, he emphasized:

"Children are curious and ask a lot of questions about the world around them. Introducing philosophy in primary and secondary schools could capitalize on this. It would help develop children's reasoning skills and prepare them to take part in debates and policy-making."

According to him, teaching environmental ethics would enable younger generations to learn about their rights, foremost among which is the fundamental right to inherit "a healthy and sustainable environment."

This article is part of a project involving The Conversation France and AFP Audio. It received financial support from the European Journalism Center as part of the Solutions Journalism Accelerator program supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. AFP and The Conversation France have maintained their editorial independence at every stage of the project.

Sylvain Wagnon, Professor of Education Sciences, Faculty of Education, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.