Career change: another obstacle course for military personnel

Our research on military personnel transitioning to civilian careers (64 interviews) reveals that it is difficult to leave a profession that requires personal aptitude and strong commitment, which forge the " unique status " of military personnel, to use the terminology of the High Committee for the Evaluation of Military Conditions.

Dominique Lecerf, University of Montpellier; Anne Loubès, University of Montpellier and Claude Fabre, University of Montpellier

Professional specificity is not, however, a concept reserved solely for the military; according to German sociologist Max Weber, it is the result of "any organization or institution with its own specific purpose."

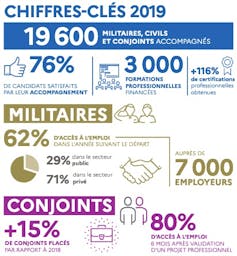

Approximately 16,000 people leave our armed forces each year. The Defense Transition Agency assists 62% of them in finding employment, which proves difficult to sustain. Ultimately, only 37% of those who leave secure the job they found with institutional assistance. The imperative of a rapid return to employment and the pressure associated with reclassification rates lead operators to favor a focus on employability and technical services. People are therefore constrained, or even essentially reduced, to a portfolio of transferable skills.

Whether forced or chosen, losing a job affects a person as a whole, not just in their professional role. Change is synonymous with stepping into the unknown, with doubt, questions, and fears; the dispositions and resources needed to overcome it are specific.

By investigating the heart of military retraining, this study highlights the need for questioning and identity support in the retraining process. It shows the urgency of a comprehensive approach that simultaneously implements the technical and psychological levers of retraining. The aim is to enable individuals to quickly take control of their career transition by understanding who they are in order to accept and decide who they want to become.

Before: a soldier, but not only that...

A person's identity is multifaceted. It is based on three dynamic pillars: personal identity (innate and acquired), role identities in their socio-professional mosaic, and finally, group identities. This results in an identity for oneself and an identity for others.

Authors' diagram

The uniqueness of the military stems from a very specific role identity—giving and receiving death in the service of arms; a strong attachment to the group—soldiers refer to each other as brothers in arms; and to the institution— based on a system of values. The demands of service can lead to self-forgetfulness, to a "merging" of the personal and the professional, to family "sacrifices"... summed up in Alfred de Vigny's maxim: "Military servitude and greatness." The difficulty of detaching oneself from a professional and group identity with a strong influence is a reality that can be found in many activities, particularly industry, health, education, trade unionism, etc.

Authors' diagram

First, job loss leads to a "loss of self," to borrow the expression coined by sociologist Danièle Linhart. This change plunges military personnel into a state of marginalization—known as liminality—which introduces chaos, suddenly imposes itself on their history, and disrupts its structure, heroes, and imagined "downfall." The anxiety that sets in thus introduces a curve of doubt similar to the grieving process, a word that often comes up among those interviewed, for whom denial, anger, bargaining, and depression lead to the final stage of acceptance: a new beginning.

A former soldier testifies:

"Having wanted to be a soldier since I was a child, I had lived my lifelong dream professionally. My life could have ended right there and then."

How can we cope with this anxiety? A process of personalization, based on identity work and the evolution of a plural identity, is likely to facilitate the transition. This is in fact a process of re-personalization, a return to one's identity foundation. This questioning would enable, in particular, an adjustment of interpersonal relationships and personal strategies forcoping with threats, and allow for the realization of projections into a new social and professional life.

Identity distancing

This perspective is all the more necessary given the profound nature of military personnel's retraining, as one interviewee explains:

"When a soldier transitions to civilian life, their relationship with the world changes. It's not just a change of job, it's a complete change of life. In fact, you go from giving your life to giving your arm; my ability to work is to offer my arms, which is very different from giving my life."

If the influence of the group that has been left behind proves to be overwhelming, identity building is altered and threatened. Distancing oneself from it facilitates the completion of identity work, in which the individual's quest for meaning is the driving force behind their actions and the key to their professional transition. A former soldier confirms the importance of this step:

"I had to figure out how to transfer my military skills so that they would fit in with the job [...] but the difficulty was that I had to build something that made sense."

In other words, soldiers must think more about who they are than what they are. At the time of the study, the Army Recruitment Service was promoting its slogan, " Become yourself!" A fortiori, when leaving, staying, becoming, or becoming again are all part of the imperative "maintaining oneself, " not only to achieve the necessary detachment, but also and above all to maintain a balance of identity and provide a foundation for the new project. Professional transition creates a changing context in which one's identity for oneself is adjusted to one's identity for others, through a degree of detachment from the group one has left, which facilitates the integration into the group one has joined. Knowing how to become is therefore a key skill to develop.

A former soldier sums up this conclusion:

"You have to take charge of your own career change and not wait for others to do the work for you."

The alternative of knowing how to become

But we only become ourselves in a given ecosystemic environment. When environmental reference points change, we must continue to become ourselves! For a smooth career transition, it is essential that the departing employee understands the need to re-situate their personal identity— who they are —within their changing plural identity— what they are.

In order to avoid getting bogged down in the process of personalization, he must take a step back from the group he has left, which continues to frame his identity for others: through its modes of operation, its value system, the roles that the individual plays or has played within it, the assets to which he has contributed, and the collective myth that he has helped to write and in which his own myth has found a place.

Taking a healthy step back should allow room for writing a new chapter in one's plural identity. Our results show that the polarization of individual identity by collective identity appears to be an obstacle to a quick return to sustainable employment: only 20% of those who left in this situation retained the job they had when they left. This finding becomes less pronounced three years after departure. In fact, the process of intentionally distancing oneself from one's identity ultimately offered a 50% greater chance of securing long-term employment.

However, this does not mean making a clean break with the past, but rather "sorting" between the temporary elements of identity for others and the permanent elements of identity for oneself. This implies that for some, the transition is a complete career change, while for others it is simply a change of direction, or even a replication of their former profession: its value system associated with the image that the individual has internalized; its normative framework and the resulting habits.

A low-cost, dematerialized psychological support "module" dedicated to identity work and learning how to become would be a start and a minimum requirement. Because the subtle engineering of humans in transition, seeking to maintain themselves in project mode, implies a profound evolution in the economic logic of support.

" Focusing on people," as is often emphasized, means putting individuals and their career plans back at the heart of the system, tailoring services and support periods to each person, and giving psychological support and consultants the necessary space and autonomy. This requires a review of service providers' specifications and the way their results are measured, beyond simply looking at re-employment rates.

For example, the degree to which an individual accepts the new project, the rate at which a validated project is implemented, or a return to sustainable employment would provide new bases for support and assessment.

Unrealistic given the state of the job market? Too costly for the community? How can we respond to these questions other than with inertia or denial? It's all a matter of priorities!

This contribution is based on the thesis "Breaking free from a strong group identity to successfully transition into a new career: The case of military personnel retraining " by Dominique Lecerf, supervised by Anne Loubès, defended on October 30, 2020..![]()

Dominique Lecerf, Associate Researcher at the MRM/GRH Laboratory, University of Montpellier; Anne Loubès, University Professor, Director of IAE Montpellier, University of Montpellier and Claude Fabre, Senior Lecturer in Management Sciences (specializing in human resources), University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.