Pension reform: what impact will it have on volunteering?

Pension reform will have consequences for future retirees and public finances, but we tend to forget that it will probably also have consequences for associations.

Andréa Gourmelen, University of Montpellier and Ziad Malas, University of Toulouse III – Paul Sabatier

Young retirees are a group whose available time and health promote volunteer work at a rate well above average.

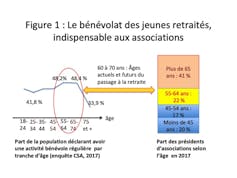

This is reflected in the high percentage of volunteers among 55-74 year olds (48.3%), the longer hours they volunteer (58% of those over 65 who are involved in an association devote more than five hours a week to it) and their key role at the head of associations, as shown in Figure 1 (based on the work of Viviane Tchernonog and Lionel Prouteau).

Andrea Gourmelen/Ziad Malas, Author provided

While many details of the future law remain to be clarified, its main principles and part of the implementation schedule are already known: it will be presented to the House on Monday, February 17, and a final vote will be held before the end of the parliamentary session in the summer of 2020.

Towards a drying up of French associations?

Some of these principles may contribute to a decline in the pool of volunteers available to associations. Beyond discussions about the pivot age, the future law gives employees more freedom to choose their retirement age and encourages them to continue working longer. If retirement starts later, logically, this should mean less time available for volunteering.

Statistically speaking, this reasoning is debatable given the increase in life expectancy and the less significant increase in healthy life expectancy.

But the logic of shifting life stages comes up against the inertia of perceptions and emotions associated with age and the time left to live. Thus, taking into account what researchers call ultimate temporal pressure (UTP)—the pressure we feel when time passes, but also becomes time left—becomes important. This is even one of the keys to understanding the voluntary commitment of retirees.

Future retirees under the universal pension plan are now 45 years old at most, and are probably not yet thinking about what they will do in retirement... But what about when they do retire? The economic and social situation will also have changed the values and priorities of future generations of retirees.

However, it is possible to envisage possible scenarios that will begin to affect volunteering within 10 years, based on the profiles of current retired volunteers that we studied in a previous article published in 2014. These profiles are characterized in particular by their ultimate time pressure and their generativity: that is, their degree of concern for future generations.

Will volunteers concerned about posterity work longer hours?

These profiles account for around 38% of retired volunteers, who appear to be deeply affected by negative feelings about the end of life and the time they have left to live. They fear the approaching death and aging. Volunteering is therefore a way for them to counteract the passing of time and make themselves indispensable in order to gain a certain amount of recognition.

Thus, they first seek to build a reputation during their lifetime, in order to transform this fame into popularity that will endure beyond their death. Leadership roles and those involving public exposure seem to particularly resonate with their motivations.

With the current reform, their careers are likely to be longer. As a result, in order to fulfill their ambitions, they may prioritize professional choices over volunteering as a "second career." The new financial incentives will reinforce this choice. Furthermore, getting involved in an association later in life would leave them less time to invest themselves and climb the association's hierarchy, which could lead to frustration among these individuals and a void in the hierarchy.

We can therefore expect them to place greater emphasis on their professional activities (working as long as possible) in order to gain recognition more quickly, as retirement can be seen as a sign of aging, which causes them anxiety.

Guilty volunteers: are numbers declining?

These retirees volunteer out of a sense of moral duty and demonstrate true selflessness. Feeling guilty for having had a good life or for being privileged, their generativity leads them to get involved in society as much as they can. The self disappears, giving way to others and the community.

Volunteering then becomes a way of giving back to society what it has given them. With this profile accounting for around 13% of current retired volunteers, is there a risk that it will disappear among future generations of retirees? Will this selflessness, linked to the need to give back to society what it has given us, remain as strong if working longer and the fear of a lower standard of living lead us to believe that society takes more from us than it gives?

Generational guilt may thus fade in favor of individual guilt (feeling that one has done better than others of one's generation), at least for the 1975-1985 generation, which corresponds to the transition phase between pension systems.

This generation may feel sacrificed and, as a result, disadvantaged compared to the baby boomer generation (which is still significant, as it accounts for nearly 24% of the French population). The reform could thus widen the gap between generations and reinforce the image of boomers as privileged, as is the case with the "OK boomer" phenomenon on social media.

This may cause difficulties in areas where this profile is most suited: charitable organizations or social assistance roles in volunteering, such as listening to people in difficulty, helping with reintegration, or distributing food.

Hedonistic and emotional: toward new temporal trade-offs?

These "hedonistic and emotional" profiles alone account for about half of retired volunteers. They include retirees who have freely chosen volunteering as an enjoyable activity, allowing them to discover new opportunities while forging human connections. Not necessarily concerned about the future of subsequent generations, they nevertheless enjoy interacting with a variety of people in their volunteer work. For them, it is important to enjoy the time they have left. They have few negative feelings about the fact that their time is limited.

At first glance, pension reform seems to have less of an impact on these profiles, given how much enjoyment they derive from volunteering. However, retiring later in life may lead to a greater sense of pressure regarding the time remaining at the end of one's working life. This could lead to increased negative feelings about the time remaining (stress, bitterness) and thus more trade-offs in how that remaining time is allocated. A shift toward family or leisure activities at the expense of volunteer work could be a possibility.

Pxhere, CC BY

From "young retirees" to "active seniors"

While the reform will allow those who have had physically demanding jobs (physical, risky, shift work) to retire earlier, and although the concept of physical hardship is still under review, it should be borne in mind that these jobs generally require little education.

However, retirees involved in associations generally have a high level of education (compared to the average level of education of their generation). As a result, future retirees who may be interested in volunteering are likely to be increasingly older (because they have had a long education, they may not be concerned by the notion of arduous work) and may quickly come to believe that they are too old to volunteer.

Should associations therefore target individuals who are eligible for early retirement? Not necessarily, because past working conditions may impact the amount of time these individuals perceive they have left to live in good health, leading them to think: "I'm too tired and worn out to work, and therefore... to do volunteer work."

So, rather than targeting "young retirees" who may perceive themselves as "too old" or "not healthy enough" depending on their previous occupation, associations should perhaps focus on active seniors. This would allow them to anticipate their objections.

The need for thoughtful engagement

For several years now, France Bénévolat has been emphasizing that successful volunteering is the result of a thoughtful commitment. And what better way to make a thoughtful commitment than to prepare for it before retirement? In addition, we know that among the working population, those over 50 are the most likely to volunteer, mainly because they do not have young children to care for.

We could also add that between the age of 50 and retirement, financial constraints are less severe. Therefore, provided that anxiety about pension amounts is alleviated, we have a population that will be receptive to volunteering, a commitment that will continue into retirement and will be accompanied by another key resource for associations: donations.![]()

Andréa Gourmelen, Senior Lecturer in Management Sciences (Marketing), University of Montpellier and Ziad Malas, Senior Lecturer in Management Sciences, University of Toulouse III – Paul Sabatier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.