Depending on the sport practiced, athletes may not have the same probability of giving birth to a girl or a boy.

A recent study has found that, among elite athletes, their sport can influence the likelihood of giving birth to a girl rather than a boy. What could be the hypotheses to explain this "oddity"?

Favier François, University of Montpellier; Florian Britto, Paris Cité University and Grégoire Millet, University of Lausanne

Sports science researchers sometimes have strange conversations: about a year ago, we were discussing the influence of sport on the gender of athletes' children. It seems incongruous at first glance, but it was said that endurance athletes had more daughters... As we discussed and looked at examples among our acquaintances and famous athletes, this rumor seemed to be confirmed. But no solid scientific work had been done on the subject, so we decided to investigate! And yes, our analysis of nearly 3,000 births confirms this idea: a top-level triathlete or cross-country skier is less likely to have a boy than a professional team sports or tennis player.

How did we arrive at these conclusions? First, we had to find the data. To do this, we used information provided by the athletes themselves via social media, specialist magazine websites, newspapers, Wikipedia entries, or directly through questionnaires. This marked the start of a long and tedious process of collecting data from professional athletes and national team selections. We noted the athletes' ages, their sports disciplines, the dates of their careers, and, of course, the year of birth and sex of their offspring. We know that in the general population, there are between 1.03 and 1.05 boys for every girl, and this ratio is very stable across the world and over time. We compared the results for our athletes with these values and also compared the different sports to see if we could identify any criteria associated with the birth of girls or boys.

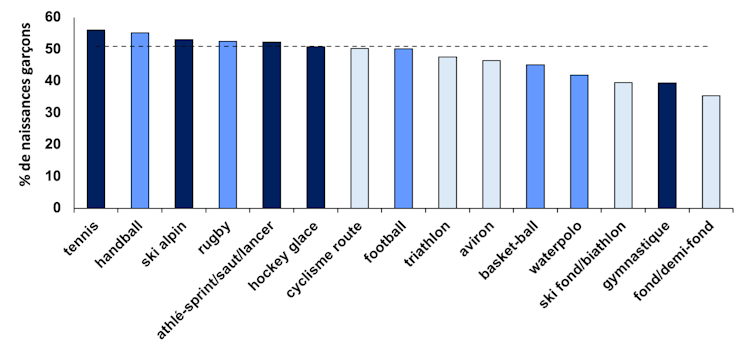

Nearly 3,000 births analyzed

Result: 2,995 births between 1981 and 2024 to athletes from more than 80 countries and 45 different sports were analyzed, of which just under 20% were female athletes (this ratio is mainly due to the availability of data, which stems in particular from greater media coverage of male athletes compared to female athletes). The first finding is that among our athletes, there are 0.98 births of boys for every birth of a girl, which is less than among non-athletes. We are on the right track. To see whether the sport influences the sex of children, we classified sports according to the percentage of male births observed in each sport and found that there are very significant differences (56% to 35% male births) between tennis and handball, and skiing on the one hand (with many boys), and cross-country skiing/biathlon, gymnastics, or long-distance and middle-distance running on the other.

Looking at these results, we see that things get a little more complicated, because gymnastics and water polo, which are not really considered endurance sports, also seem to influence the sex of athletes' offspring, leading to an increase in the number of girls born. On the other hand, another factor emerges: female athletes give birth to significantly fewer boys than male athletes (0.85 boys for every girl, compared to 1.02 for every girl among men).

To gain a clearer picture, the different disciplines are grouped into four categories: endurance (cycling, cross-country skiing, etc.), power (downhill skiing, jumping and throwing, etc.), mixed (team sports), and precision (shooting, golf, etc.). We then add the criteria: the athlete's gender and date of birth in relation to their sporting career (during or after their career). We then perform a classification tree analysis. This involves separating the sample into distinct subgroups using the specified criteria, if these have predictive power over the gender of the offspring.

By conducting this statistical analysis, we can conclude that it is indeed the sport discipline that has the greatest impact, with athletes practicing endurance or precision sports producing significantly more female births and fewer male births than the other two disciplines (mixed and power). Furthermore, within the subgroup of athletes who practice endurance or precision sports, the gender of the athlete themselves is a predictor of the gender of their offspring: female athletes in this subgroup give birth to 0.7 boys for every girl, compared to 0.91 for men.

Finally, the last effect, among endurance and precision athletes, is that having a child during or after their career has a significant impact, since the probability is only 0.58 boys for every girl when the birth occurs during their career, compared to 0.81 after their career.

Finally, the subgroup for which the effect of high-level sports practice is most pronounced is that of female athletes who practice endurance or precision sports and who have a child during their career. Among them, the probability of having a girl or a boy is 63% vs. 37%, compared to approximately 49% vs. 51% in the global population.

What are the assumptions?

How can such a difference be explained? At this stage, we can only speculate.

One of the causes could be linked to the hormonal profile of the parents at the time of conception. High levels of testosterone or estrogen are thought to favor male births, unlike progesterone or cortisol. The testosterone/cortisol ratio has been proposed in sports as a marker of overtraining.

Another physiological cause could be the energy expenditure associated with physical activity. Indeed, embryonic development is more energy-intensive for male fetuses than for female fetuses.

The number of hours spent training and the intensity of the training sessions would alter the hormonal status and/or energy levels of the body prior to conception, which could influence the sex of the athletes' offspring.

In line with this hypothesis, a study of Chilean soccer players showed that those who trained the most had more daughters than the others. The same observation was made in animals: pregnant female mice that run the most produce fewer male offspring. The number of hours of weekly training would also explain the low number of boys among gymnasts and polo players, two sports that require a significant amount of training. But psycho-sociological factors could also influence the sex of athletes' children. For example, a good financial situation is associated with an increase in male births in the general population.

Differences in income between sports disciplines and between men and women, or uncertainty about life after retirement, could therefore contribute to the variations observed. The list of other parameters likely to influence the sex of athletes' children is long (partner profile, possible use of certain pharmacological substances, dietary/energy balance, political situation in the country, etc.). New standardized studies will therefore be necessary to elucidate these observations. From a physiological hypothesis perspective, it would be interesting to compare the hormonal profile, energy expenditure, and training volume of athletes who are parents of boys with those who are parents of girls. More in-depth studies on the quality of male athletes' sperm and the adaptation of female athletes' genital tract in response to their training would also be very interesting. Finally, it would also be relevant to measure the impact of better socio-economic management of female athletes' careers on the sex of their offspring.

Favier François, Professor Sports Science, University of Montpellier; Florian Britto, Researcher, Paris Cité University and Grégoire Millet, Professor of Environmental Physiology and Exercise Physiology, University of Lausanne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.