Spirus Gay, the anarchist acrobat who turned his life and body into a political statement

Spirus Gay (1865–1938), circus artist and anarchist activist, embodies a rare figure from the early20thcentury: one of total commitment, combining art, body, ethics, and politics. Defying rigid categories, his life was marked by a joyful, consistent radicalism, where acrobatics went hand in hand with education, naturism with trade unionism, and pamphleteering with solidarity.

Sylvain Wagnon, University of Montpellier

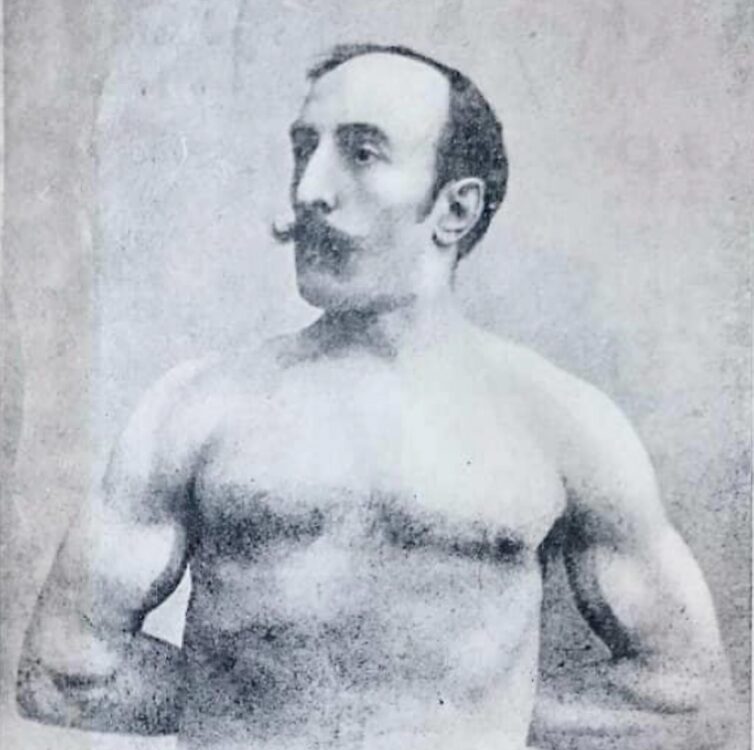

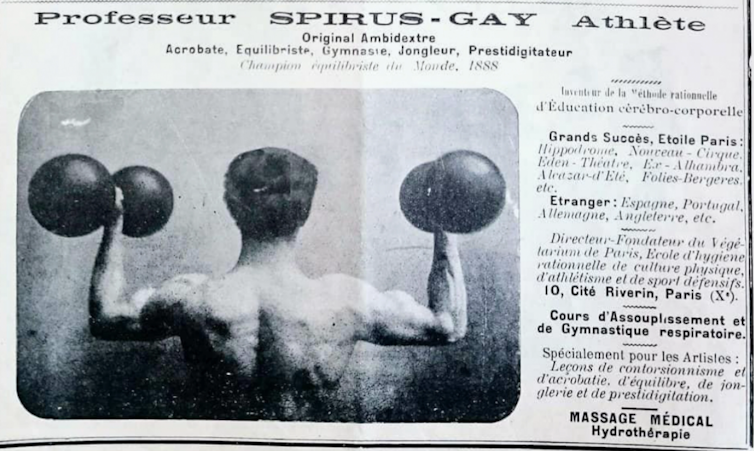

How can Spirus Gay be defined? Acrobat, juggler, tightrope walker, anarchist, trade unionist, free thinker, pamphleteer, naturist, freemason, but also educator... Joseph Jean Auguste Gay, known as Spirus Gay (1865-1938), defies any attempt at classification. His rich and varied career embodies a rare example of total commitment, where body, mind, art, and political thought intertwine to question and subvert established norms.

It is in this coherent articulation between physical action, intellectual engagement, and radical activism that a truly unique path emerges.

Would our compartmentalized and fragmented society still have room for a Spirus Gay today?

Why write about Spirus Gay?

For a historian, writing about such a figure is a challenge. At first glance, there are few traces of him. He left behind no major works or famous manifestos. He did not run an influential newspaper or found a theoretical movement. And yet, he is there, in the margins and interstices of the history of French anarchism. As an activist, he participated in the struggles, battles, experiments, and utopias of the late19thand early20th centuries.

His career embodies a way of living anarchism: in the body, in gestures, in the harmony between personal life and individual and collective commitment. Because it illustrates that rare consistency between the ideas we defend and the life we lead. Because it forces us to rethink categories: artist or activist? Intellectual or manual worker? Thinker or teacher?

As with biographical work on women's history, the challenge is to break away from conventional genres and avoid the temptation to simplify, linearize, or betray a rich and varied life. Conversely, it is not a question of constructing a legend, but of using sources and historical rigor to understand what this unique life can tell us today. It is a matter of piecing together a puzzle from scattered archives and forgotten journals, aphorisms and articles by Spirus Gay, and tenuous traces (more than 600 mentions in the press of the time, and some fifteen signed texts). It is a matter of writing without erasing the contradictions, the gray areas, and the silences.

An accomplished artist

A figure of Parisian music hall in the late19thcentury, Spirus Gay embodied a versatile artist: tightrope walker, juggler, illusionist, ventriloquist, and conjurer, he performed on Parisian stages, from the Folies-Belleville to the Folies Bergère. Between marginality and mass culture, behind the prestige of posters and titles such as "king of tightrope walkers" or "world champion" of bodybuilding, lies a much harsher reality.

Like many variety artists, Spirus Gay lives in constant instability, dependent on performance fees, exposed to injuries, stage accidents, and the hard knocks of life. On several occasions, the activist and artistic community has had to organize fundraisers to provide for his needs, repair his damaged tools, or help him cope with illness.

This precariousness does not prevent him from fighting numerous battles for the recognition of artists in the "living arts." Spirus Gay is fervently committed to defending the rights of artists, whom he considers to be fully integrated into the working class.

In 1893, he joined the union council of the Syndicat des artistes dramatiques (Dramatic Artists' Union), then in 1898 became secretary of the Union artistique de la scène, de l'orchestre et du cirque (Artistic Union of the Stage, Orchestra, and Circus). This role allowed him to organize collective actions, combining concerts and militant solidarity. As spokesperson, he defended opera singers and called for direct action against employer abuse.

Self-taught, Spirus Gay also published in the newspaper Le Parti ouvrier, the organ of the Revolutionary Socialist Party, a dozen articles outlining his vision of society and the world. These writings, mostly aphorisms, are a unique literary genre that questions his own education and training. The apparent astonishment at this union of body and mind is still based today on deeply rooted prejudices that establish a boundary between the entertainment artist and deep and continuous political commitment, but also a hierarchy between intellectual and manual functions.

Comprehensive education as a revolutionary project

Spirus Gay is also an educator, a direct heir to the educational principles championed by the libertarian educator Paul Robin from 1869 onwards. For Robin, holistic education is based on a simple but profoundly subversive principle: rejecting the dissociation between the intellect, the body, and the emotions. Developing "the head, the hand, and the heart" in a harmonious way would free the individual from the alienation produced by a school system considered authoritarian, by the factory, by the Church, or by the State.

Spirus Gay applied this principle in his life as well as in his educational practices. The gym he founded in Paris in 1903, the Végétarium, became a space for educational experimentation and training in freedom, where physical culture, vegetarianism, "cerebro-corporal" education, and healthy living were combined as tools for emancipation. For him, acrobatics became a political act, movement a philosophy of resistance. Education, seen as a lifelong process, was as much about developing the mind as it was about developing the body. As a libertarian naturist and naturist activist, he helped found the first naturist community in Brières-les-Scellés, in what is now the Essonne department, and campaigned against the ravages of alcohol.

A thinker on political altruism

A free thinker, anticlerical, atheist, and Freemason, Spirus Gay also embodied a humanist intellectual commitment, nourished by the ideals of freedom of conscience and individual and collective emancipation. "I believe in divine equality in a society without religion or masters, " he wrote in 1894.

His writings outline an ethical, committed, and radical philosophy. In them, he advocates for a society based on equality, justice, the rejection of authority, and a relentless fight against capitalist selfishness.

For him, altruism is not a moral stance, but a political weapon: a way of disarming the violence of a world based on exploitation and competition. This notion is reflected in the conceptof"effective altruism," defined by philosopher Peter Singer.

The subversive power of a life

Spirus Gay cannot be summed up. He defies classification and rejects labels. And that's just as well, because we should be wary of pantheons: they freeze what they celebrate.

Her trajectory is ultimately a proposition: that of embodied and consistent radicalism. Her life offers constant resistance to compartmentalization, hierarchies, and identity assignments. It articulates aesthetic gesture, intellectual rigor, and commitment.

Spirus Gay takes a deep dive into how we live out our ideas: how can we not separate our beliefs from our daily lives, our politics from how we live, eat, and breathe? His journey is an invitation to think, to fight, to live.

Sylvain Wagnon, Professor of Education Sciences, Faculty of Education, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.