Oil at over $80 a barrel: bad for the economy, good for the climate?

When he left the government, Nicolas Hulot cited the increase in greenhouse gas emissions in 2017 as one of the reasons for his resignation. This increase, which is highly damaging to the climate, is primarily the result of the fall in oil prices between 2014 and 2017; which boosted economic activity and encouraged greater consumption of petroleum products, which had become less expensive for our wallets.

Christian de Perthuis, Paris Dauphine University – PSL and Boris Solier, University of Montpellier

Shutterstock

Reversal of the situation in 2018: at over $80 per barrel, the price of Brent crude oil reached its highest level in four years at the beginning of October (see figure below).

Bad news for the economy, but a virtuous incentive for the climate? Let's take a closer look.

tradingview.com

Why high oil prices weigh on the economy

The rise in oil prices erodes household purchasing power, in a similar way to a carbon tax without a redistribution mechanism for the most modest households, and weighs on the production costs of energy-intensive activities.

According to the Mésange macroeconometric model used by the Ministry of Economy, a 20% increase in the price per barrel causes a 0.2 point reduction in GDP after two years. The doubling of crude oil prices over the past year and a half could therefore cost one point of growth. Economists take note!

One might wonder whether this short-term view is not overly simplistic. The rise in oil prices should only result in a transfer of value between producers and consumers, leading to a geographical shift in added value rather than a decline in activity.

This reasoning holds true if we consider only the flow of goods. However, we must also consider debt stocks. In Western economies marked by decades of debt, the weight of private debt is a major weakness in the system. We saw this, for example, during the 2008 crisis, when oil prices rose above $140 per barrel, contributing to a growing number of American households being unable to repay their mortgages and precipitating the collapse of the American investment bank Lehman Brothers.

It is therefore necessary to take into account the effect of rising oil prices on debt levels, which structurally weaken economies, in order to accurately anticipate their economic impact.

Expensive oil, not so good for the climate

From the demand side, higher oil prices encourage consumers to be more careful about their purchases of fuel, heating oil, and gas, whose prices are increasingly correlated with the price of oil. This penalizes consumers but is beneficial for the climate. For an environmental activist, there is no contest between losing one percentage point of growth and saving the planet.

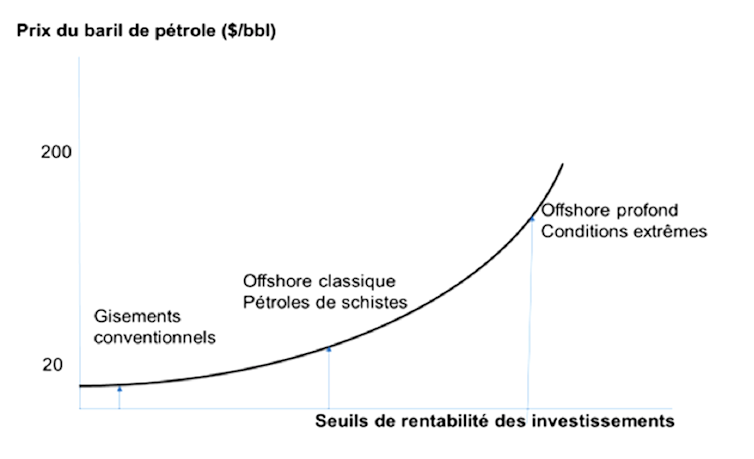

But at the same time, rising oil prices provide another incentive for producers. As the price per barrel rises, it becomes increasingly profitable to extract oil from less favorable locations, which are therefore much more expensive: several thousand meters below sea level, in the Arctic, or from oil shale. With each upward cycle in oil prices, we see a resurgence in exploration and production investments that will drive tomorrow'sCO2 emissions.

This is the diabolical side of the oil rent economy for the climate. It has two sides: scarcity rent and differential rent.

When oil becomes relatively scarce, for geological or geopolitical reasons, the price per barrel skyrockets. It can exceed $100 per barrel, as it did in 2008 and 2011-2014. The rise in oil prices increases the scarcity rent captured by producers, encouraging them to invest in new capacity and unconventional extraction technologies... and thus increasing the potential forCO2 emissions in the medium and long term (see figure below).

The excess supply eventually catches up with demand—which has slowed due to the price increase—and causes prices to fall. This is the cyclical phenomenon of "oil counter-shocks." This decline stimulates demand and promotes a resumption ofCO2 emissions. This is bad news for the climate in the short term, especially as producers are proving unexpectedly resilient to falling prices. This is where the second aspect of oil revenues comes into play: differential revenues.

The vast majority of producers pocket a second bonus resulting from the difference between their operating costs and those of fields that are less well located or produce lower quality crude. When the price per barrel falls to $20, the least well-positioned producers suffer. But the Ghawar field in Saudi Arabia is still very profitable: its production cost is around $5 to $7 per barrel. Its operator is not about to exit the market.

It feels like we'll never get out of this! However, there is a tool that can help us break out of this vicious cycle: carbon pricing, which provides incentives for climate action on both the producer and consumer sides. This aspect is explored in depth in a recent publication by the Climate Economics Chair on energy transition and the ticking of the climate clock.

Carbon rent versus oil rent

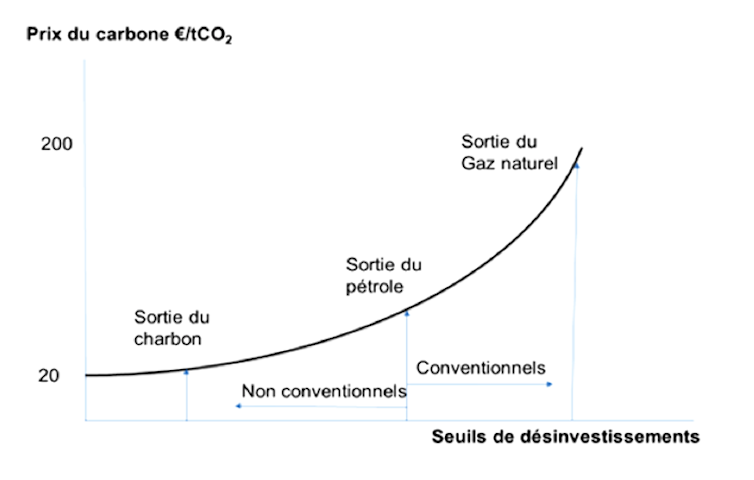

The cornerstone of the carbon economy is the value placed on climate protection through aCO2 price. This price is a cost that must be applied to all anthropogenicCO2 emissions. It does not matter whether it is introduced into the economy via a tax, a permit market, or more implicitly through a set of standards. Its distinctive feature is that it sends the right incentives to both the supply and demand sides.

For consumers, the introduction of theCO2 price leads to an increase in the cost of different energy sources in proportion to their respectiveCO2 content. The incentives introduced are twofold: on the one hand, to save energy whose average cost is increasing; on the other hand, to replace the mostCO2-intensive sources with non-carbon or low-carbon sources.

In the carbon economy, virtuous incentives for consumers are no longer offset by a counteracting effect on the producer side, where rising prices encourage producers to expand their fossil fuel production capacities. As soon as the price of carbon becomes the benchmark for the energy transition, it becomes less and less profitable to invest in fossil fuels as the cost ofCO2 rises (see figure below). The rising cost ofCO2 discourages both producers and consumers from using fossil fuels that emitCO2.

As long as the carbon rent economy has not supplanted the oil rent economy, there will be a contradiction between the functioning of the markets and the goal of reducing CO₂ emissions.2. And as a result, there is a contradiction between the objectives set by the Minister of the Environment and the traditional indicators of employment, purchasing power, and growth that guide government action.![]()

Christian de Perthuis, Professor of Economics, founder of the Climate Economics Chair, Paris Dauphine University – PSL and Boris Solier, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Associate Researcher at the Chair in Climate Economics (Paris-Dauphine), University of Montpellier

The original version of this article was published on The Conversation.