Exotic viruses in France: what do you need to know about chikungunya?

Since the beginning of summer, a record number of indigenous cases of chikungunya virus infections have been reported in France. Here is what you need to know about this virus, which is spread by mosquitoes belonging to the Aedes genus, such as the tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus.

Yannick Simonin, University of Montpellier

The chikungunya virus was first described in 1952 in Tanzania, on the Makonde plateau. Its name derives from the word meaning "to become contorted" in the Kimakonde language, spoken mainly in southeastern Tanzania. It describes the way in which the posture of patients, crippled by severe joint pain, changes during the course of the disease.

While most patients eventually recover completely, this virus is particularly dangerous for newborns and the elderly. In many cases, it can also cause serious complications, including joint pain and chronic fatigue. These symptoms can persist for several months or even years, significantly impacting the quality of life of those affected.

Biology and transmission

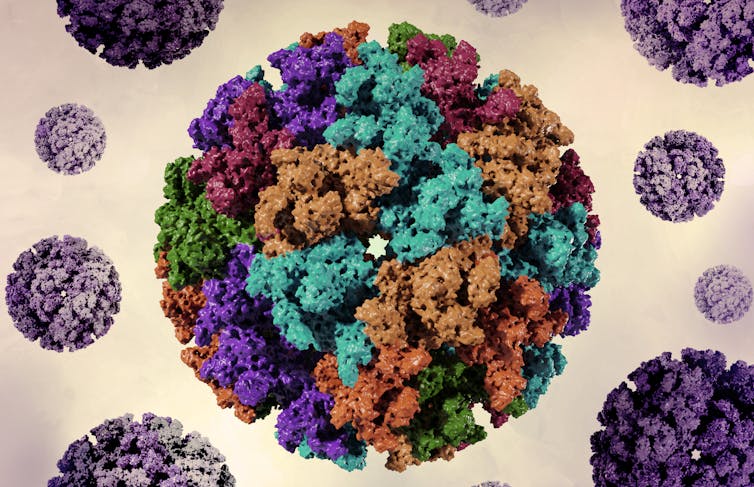

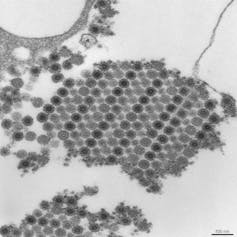

The chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is an arbovirus, meaning it is transmitted by arthropods (arthropod-borne virus). It is an enveloped virus with an RNA genome.

It is spread by female mosquitoes of various species belonging to the genus Aedes. The speciesof Aedes most often responsible for its transmission are Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, the infamous tiger mosquito. In rural areas of Africa, Aedes furcifer and Aedes africanus are also involved, as well as several other speciesof Aedes.

On the African continent, various animal reservoirs have been identified (primates, rodents, birds, etc.) that are involved in the virus cycle. The virus can therefore be transmitted from animals to humans, making it a zoonosis.

Livestock can also be a reservoir, but its role in transmission is not clearly determined.

Although mosquitoes of the genus Aedes bite throughout the day, they are most aggressive in the mid-morning and mid-afternoon. The risk of disease transmission is therefore highest during these periods.

When a female mosquito feeds on an individual whose blood contains the virus, the virus multiplies in the insect's body for about ten days, particularly in its digestive system and salivary glands. When the infected mosquito bites a new target, it systematically injects its saliva, mainly to prevent the blood from clotting and thus facilitate the blood meal. This is how it transmits the virus.

Once in the bloodstream of its new host, the virus multiplies again within a few days. Mosquitoes that bite the newly infected individual will in turn become infected, continuing the cycle of virus transmission... This is how outbreaks of indigenous cases, and even epidemics, occur.

During human outbreaks, it is therefore the transmission of the virus from one person to another that sustains the epidemic. A person carrying the virus can transmit it during the "viremic" phase (when it is present in the blood), i.e., one to two days before the onset of symptoms and up to seven days after.

Contamination can also occur through exposure to contaminated blood (transfusion, puncture with a contaminated needle, splashing or contact, etc.). Furthermore, although rare, the virus can also be transmitted from mother to child during childbirth, with serious consequences for the newborn.

Highly fragile outside its host, the chikungunya virus does not survive well in the environment. Unlike many other viruses, it is therefore not transmitted via contaminated objects or surfaces.

Symptoms

According to studies, infection with the virus is asymptomatic in only 5 to 40% of cases. The majority of infected individuals therefore develop symptoms, unlike other mosquito-borne viruses such as dengue or Zika.

In symptomatic individuals, signs of the disease usually appear one to twelve days after being bitten by an infected mosquito (on average, two to three days).

This fever is accompanied by joint pain, which is often severe and mainly affects the extremities (hands and feet, wrists, ankles) and knees, and more rarely the hips or shoulders. This pain is mainly related to inflammation resulting from the infection. Patients also often experience headaches and severe muscle pain (in 70% to 99% of cases), as well as a rash on the limbs and trunk.

Most patients recover completely. The fever usually disappears within two to seven days, the rash within two to three days, and joint pain within a few weeks.

However, in some people, particularly those over 40 or those with a history of joint disease, a chronic form of the disease may develop. Certain symptoms then persist. Joint pain in particular can last for several years after infection. This situation can be very debilitating on a daily basis, especially as it can be associated with chronic fatigue.

Some studies estimate that between 30% and 40% of symptomatic adult patients still experience persistent joint pain beyond three to six months, while 5% to 20% of symptomatic patients still reported these symptoms two years after infection. Far from being trivial, these chronic conditions can therefore represent a very heavy societal burden, both in terms of health and economics.

A few occasional cases of ocular, neurological (encephalitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome), and cardiac (myocarditis) complications have also been reported.

Fortunately, deaths from chikungunya are rare (between 0.1 and 1 per 1,000 symptomatic cases). They mainly affect newborns, for whom the disease is very dangerous, causing neurological and cardiac problems, as well as the elderly or people with comorbidities (the virus aggravates underlying conditions).

Following exposure to the virus, our bodies develop lasting immunity that generally persists for several years, or even decades. In many cases, protection may even last a lifetime. Reported cases of reinfection are very rare, suggesting that this acquired immunity is sufficient to protect most people exposed to the virus.

Diagnosis and treatments

As the symptoms are very similar to those of other viruses, such as dengue fever or Zika virus, diagnosis can be difficult.

The virus can be detected in blood samples by RT-PCR during the first week of the disease. Later (after the fifth day), the infection can also be confirmed by testing for antibodies against the virus.

There is no antiviral medication for the chikungunya virus. Treatment consists of relieving symptoms by administering painkillers/antipyretics, such as paracetamol, to combat pain and fever, as well as anti-inflammatory drugs to treat joint problems.

Since June 2024, a vaccine against chikungunya, the Ixchiq vaccine from Valneva, has been authorized for marketing in the European Union. It is a live attenuated vaccine: it contains a strain of the chikungunya virus that has been weakened in the laboratory and can no longer cause the disease, but can stimulate the immune system.

Implemented during the major epidemic that affected Réunion in 2025, vaccination was suspended for individuals aged 65 and over, with or without comorbidities. This was because several cases of serious adverse effects were reported in this age group. Further investigations are underway to assess the benefit-risk balance in older people and adapt vaccination recommendations accordingly.

Epidemiology

The chikungunya virus has been circulating for several decades in Africa, India, and Asia, as well as in the Indian Ocean. It was the epidemic that struck Réunion, as well as Mauritius, Mayotte, and the Seychelles, in 2005-2006, affecting 38.2% of the population of Réunion, that brought it to the attention of the French public.

Before this first major epidemic, Réunion was not an area where the chikungunya virus circulated, as Aedes aegypti, the main mosquito vector for this virus, is not found there. The tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus was present, but was not known to transmit the virus. It was then discovered that a mutation had enabled it to adapt to this mosquito, which became a new vector. Several strains of the chikungunya virus are now circulating, depending on whether they are adapted to Aedes aegypti or the tiger mosquito. Since this change, the virus's range has changed considerably.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), since 2004, outbreaks of chikungunya have been reported in more than 110 countries in Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas. They have become more frequent and widespread as populationsof Aedes aegypti orAedes albopictus have expanded.

In addition, adaptations enabling the virus to be more easily transmitted by the tiger mosquito have been detected. The fact that the virus has been introduced into populations that have never been exposed to it (immunologically naive) also explains the increase in the frequency of outbreaks.

Situation in France

In France, the risk of transmission of the chikungunya virus concerns both regions where Aedes aegypti is established, such as the Antilles (Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Martin, Saint Barthélemy) and French Guiana, but also those where the tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) is present, such as Réunion and mainland France. In Mayotte, which is home to both species of mosquito, the risk is high, particularly due to the favorable humid tropical climate.

It is estimated that around 80% of French departments have conditions conducive to the emergence of the disease, particularly due to the continued spread of the tiger mosquito in France. This mosquito is well established there: in January 2024, it was present in 78 of France's 96 departments, not only in the south, but also in the Île-de-France region and as far east as the eastern part of the country.

Domestic cases of chikungunya—linked to infections within the country rather than to travelers who were already infected upon arrival—have been recorded in mainland France in the past. The very first domestic case of chikungunya in mainland France was identified in Fréjus, in the Var department, in September 2010. Since then, several sporadic outbreaks have been reported, mainly in the south of France, with an outbreak of 11 cases in Montpellier (Hérault) in 2014 and 17 cases in Var in 2017.

The chikungunya virus then became less prevalent, but in 2024, the first indigenous case was detected in Île-de-France, where the tiger mosquito has become established in recent years. The year 2025 is shaping up to be a record year, driven by the intense circulation of the virus in Réunion, then in Mayotte: by early July, around 30 indigenous cases had already been detected in mainland France.

Preventing the disease

Currently, the only way to combat the disease is to protect yourself from bites and fight the mosquitoes that spread it.

To avoid being bitten, wear light-colored clothing (which reduces visual and thermal attractiveness to mosquitoes) that is loose-fitting and covers the skin, use skin repellents, and install mosquito nets (around your bed, on your windows, etc.).

To reduce the development of mosquito larvae, it is recommended to empty all containers of standing water, including flower pot saucers and watering cans, and to cover rainwater receptacles, especially during periods of heavy rainfall.

When a case of infection is reported, mosquito control operations are carried out in the vicinity of the detected cases, accompanied by awareness-raising activities targeting the general public and healthcare professionals (collaboration between regional health agencies, Santé publique France, and mosquito control agencies such as Altopictus orthe Interdepartmental Mosquito Control Agreement).

Tests to control mosquito vector populations using techniques such as the sterile insect technique are also underway.

Yannick Simonin, Virologist specializing in the surveillance and study of emerging viral diseases. University Professor, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.