How synthetic amphetamines became popular

In an interview published on April 18, 2021, French President Emmanuel Macron called for "launching a major national debate on drug use." The interview focused primarily on the repressive aspects of drug policy, and the effectiveness of the measures envisaged immediately became the subject of controversy.

Edouard TUAILLON, University of Montpellier

However, a consensus should emerge from the debate regarding the recognition of addiction as a major public health risk.

The use of amphetamines (psychotropic stimulants), which has been documented for over a century, should not be overlooked in this awareness. Indeed,the emergence of new forms of drug addiction associated with amphetamines of the cathinone family is now a cause for concern in France.

A brief (medical) history of synthetic amphetamines

The first chemical purification of an amphetamine (ephedrine) is attributed to Nagai Nagayoshi, a Japanese pharmacist, and dates back to 1885. The synthesis of ecstasy (or MDMA, for 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine) by Merck Laboratories dates back to 1912, and the first synthesis of a cathinone (β-keto-amphetamine) to 1929.

In the first half ofthe 20th century, the effects of these synthetic molecules captivated chemists and aroused the interest of the medical world.

Their sympathomimetic (stimulant), anorexigenic (appetite suppressant), and psychostimulant (performance-enhancing) properties led to the commercialization of the first amphetamine-based drugs: a bronchodilator with Benzedrine® in 1934 in the United States (an amphetamine sulfate), an appetite suppressant with Obetrol® in the 1950s, also in the United States (a combination of amphetamine salts), and an energizer with Pervitin® (a methamphetamine) in Germany in the late 1930s.

A powerful methamphetamine, this latter molecule was available in pharmacies without a prescription and widely distributed to German troops during World War II. Thanks to its long-lasting stimulating effect, it is believed to have played a decisive role in the early stages of the conflict in the success of theblitzkrieg strategy, enabling soldiers to march and fight without sleep for several days.

The medical use of amphetamine derivatives continued after the war. At the end ofthe 20th century, psychostimulants such as Ordinator® (which ceased to be marketed in 1997) were prescribed to combat attention deficit disorders, as were appetite suppressants such as Isomeride® and Mediator® (prescribed for metabolic disorders, particularly diabetes). They were withdrawn from the market in 1997 and 2009, respectively, due to serious adverse effects, resulting in several convictions for Laboratoires Servier.

Today, the following drugs remain available but with significant prescription restrictions: Zyban®, as an aid to smoking cessation, and Ritalin® for attention deficit disorder in children and narcolepsy in adults. The latter, whose medical benefits have been confirmed by the French National Authority for Health, is probably the most medically useful drug to date.

From natural role to first consumption

The use of amphetamines does not date back to their discovery through synthetic chemistry. These compounds existnaturally in certain plants. There, they act as defense molecules against herbivores, like other plant alkaloids.

Ephedrine was purified from a plant used in Chinese medicine – Ephedra sinica. However, the best known and most important plant in social and economic terms is khat, from its Latin name Catha edulis, whose freshly harvested leaves contain β-keto-amphetamine or cathinone (which degrades rapidly after harvesting).

Khat is believed to originate from Ethiopia, where it grows wild in temperate areas at altitudes above 1,500 meters with good rainfall. These growing requirements, which are similar to those of Arabica coffee, have allowed khat cultivation to spread to certain areas of the Arabian Peninsula, East Africa, and Madagascar.

Khat consumption may date back to before the year 1000, although it appears to have intensified from the15th century onwards. In Yemen, where around 60% of the population consumes it (30% in Ethiopia and Somalia), its cultivation accounts for nearly 6% of gross domestic product and employs 14% of the working population.

DEA

For consumers, accessing the psychotropic effects of cathinones is not easy. First, they must obtain freshly cut branches and then chew the bitter leaves at length to extract the active ingredient. A 500-gram bunch of branches, or about 150 grams of leaves, requires two hours of chewing.

Consuming khat in the traditional way therefore takes time, but also money—to the detriment of children's health or education.

From ecstasy to synthetic cathinones

Compared to khat, synthetic amphetamines offer tenfold psychotropic effects, while being easier to produce, transport, store, and consume.

In France, amphetamines have been classified as narcotics since 1967. Their rise in popularity as a recreational drug in the 1990s is linked to the advent of electronic music and rave parties: ecstasy (MDMA) was used as a party drug for its stimulating effects and ability to facilitate social interaction.

The turn of the 2000s was marked by the emergence of the online market for synthetic drugs, or new psychoactive substances (NPS). These include various types of psychotropic drugs, mainly cannabinoids, amphetamines, opioids, ketamines and, since the 2010s, synthetic cathinones – the beefed-up cousins of the khat alkaloid.

With these drugs, amphetamines moved beyond occasional and marginal use by a small number of experimenters to reach a large, socially well-integrated population of regular users.

A drug that activates the reward system

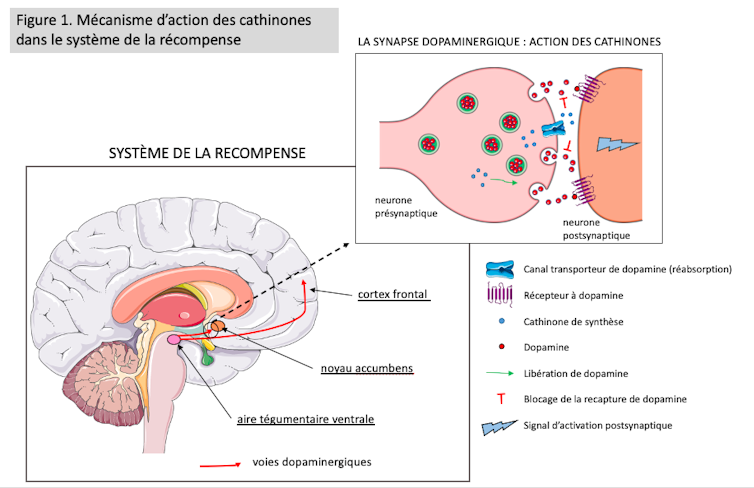

To understand the current dangerous popularity of cathinones, we need to look at how amphetamines affect our brains.

The structure of cathinones is similar to that of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that plays a major role in the reward circuit. The reinforcement/reward system is present in many animals (fish, birds, mammals), where it promotes behaviors essential to the perpetuation of the species: eating, learning, reproducing, and socializing. Cathinones act directly on this system.

After ingestion, inhalation, or injection, cathinones, which are small in size, easily cross the blood-brain barrier that protects the brain. They then interact with dopamine neurons, preventing its reuptake and promoting its release. Through these mechanisms, cathinones induce a considerable increase in dopamine. In rats, 40 minutes after administration of a standard dose of cathinone, the increase in dopamine levels is around 500%.

E. Tuaillon, Provided by the author

This influx of dopamine activates the reward system circuits. It is these stimulating and entactogenic effects (altering the desire for physical contact) that consumers seek, particularly in sexual use.

In the absence of further doses, dopamine levels drop rapidly and return to normal after approximately 180 minutes. A brief withdrawal syndrome (comedown) is frequently reported by users 24 to 48 hours after taking the drug, characterized in particular by fatigue and a general feeling of negativity (dysphoria).

The use of amphetamines inthe 20th century was thus marked not only by easier access, thanks to chemical synthesis, but also by the temptation to improve one's physiological abilities—often in a festive context.

In this age of augmented reality and instant gratification, cathinones have become the bearers of a deceptive promise to easily satisfy our desires...![]()

Edouard TUAILLON, University Professor and Hospital Practitioner. Areas of expertise: infectious diseases, virology, sexual health, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.