Toads, fish, and nematode worms: the space station's strange menagerie

They are called "model organisms": flies, mice, zebrafish, frogs, and nematode worms are all animals used by researchers for experiments, mainly because their biological structures are simpler than those of humans.

Simon Galas, University of Montpellier

This is crucial for fundamental biology and human health studies, and it can be done on Earth as well as in space. Witness the recent NASA mission "Worm in Space," launched in December 2018, which sent 360,000 Caenorhabditis elegans roundworms into space!

Animal experimentation in space is nothing new. A survey of missions conducted by NASA from 1965 to 2011 shows that no fewer than 382 experiments were carried out on various platforms: the Gemini capsule, biological experiment satellites, NASA shuttles, the NASA/MIR platform and, more recently, the International Space Station (ISS), which has been in low Earth orbit since the 2000s.

The aim is to better understand the effects of the space environment on living systems, and on humans in particular. Astronauts undergo gradual physiological changes that become more pronounced as their stay progresses. These changes can lead to an increased risk of several pathologies, including fractures, visual impairment, intracranial pressure, anemia, muscle atrophy, acute radiation syndrome, and immune system impairment. The use of model organisms subjected to the same constraints as astronauts can help prevent the emergence of these problems.

NASA

Model organisms were also used very early on in space missions to define the fundamental behaviors of living organisms. One example: how can Earth's gravitational force influence living organisms and their development from fertilization onwards? Answering this question required numerous model organisms (plants, insects, fish, amphibians, small mammals) and no fewer than fifty experiments conducted in space.

A fertile toad

As early as 1965, frog eggs and vinegar fly larvae (Drosophila melanogaster) carried aboard the Gemini mission showed normal development in the absence of gravity. Embryonic development was also tested in space during a famous experiment in 1992 (frog embryology experiment, Space Shuttle Spacelab Japan mission STS47) conducted with a frog called Xenopus (Xenopus laevis), which showed that Earth's gravity was not required for ovulation, fertilization, embryonic development, or the formation of tadpoles capable of swimming.

NASA

Experiments on other models have shown that the most important processes of reproduction and development are independent of the degree of gravitational force. One such experiment, conducted in 1979 during the Russian Cosmos 1129 mission, demonstrated the ability of pregnant rats to carry normal pregnancies. However, subsequent experiments on very young rats revealed sensory-motor deficits and demonstrated reductions in motor neuron growth, indicating the existence of a period of sensitivity to gravitational force in the sensory-motor system during post-embryonic development.

Some very important experiments have also been carried out in the field of microbiology and infectious diseases. When we consider the growing importance attached to our microbiome, which weighs around 2 kg, we quickly become concerned about the possible changes that could occur to our microbial commensals in space!

Virulence in space

In 2006 and 2007, bacteria such as Salmonella enterica typhimurium (the infectious agent responsible for salmonellosis), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (nosocomial infections), Candida albicans (fungus responsible for candidiasis), and Streptococcus pneumoniae (responsible for pneumonia) sent into space revealed the emergence of virulence that had not developed in control cultures on Earth. Analysis of these bacteria revealed that they owed their virulence in space to a single gene (Hfq), demonstrating the immediate value of this discovery in preparing astronauts for their journey, but also in improving our understanding of these infectious bacterial agents, which are increasingly resistant to treatment and responsible for numerous deaths each year on Earth.

Wikipedia

Another important topic: astronauts' muscles change rapidly in space due to microgravity. Experiments to assess muscle changes in rats in space were conducted by NASA as early as 1965. These experiments demonstrated a rapid decrease in muscle contraction strength, an increase in muscle contraction speed (velocity), a decrease in resistance with an increase in muscle fatigue, and a shortening of muscle fiber length. In both rats and humans, this latter phenomenon has been associated with the fetal posture adopted in space, which leads to slow muscle atrophy.

The changes in muscle physiology observed in rats during space flights have been verified in humans and have led to the development of a set of exercises (walking and jogging on a treadmill) that astronauts must perform every day for two and a half hours in order to slow down these changes, which can affect muscles very quickly at the beginning of a space mission.

The list below provides examples of observations made on model organisms during space missions related to human health:

- Chicken, gecko, quail, mouse, rat for observations on bone physiology in space;

- Fruit flies (Drosophila), human cells in culture, mice, rats for observations on the immune system's reactions to microgravity;

- Bacteria, fungi, human cells in culture, yeast for observations on microbial growth and virulence;

- Chicken, mouse, nematode, rat for observations on muscle physiology in space.

- Crickets, fish, quail, mice, newts, rats, toads, and snails for neurophysiological observations.

"Worm in space"

NASA

The "Worm in Space" mission in December 2018 highlights the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. This round, non-parasitic worm, measuring one millimeter in length, can be found on most continents and feeds on bacteria in fungi, plants, or decaying fruit.

No fewer than three major discoveries in modern biology have already been made thanks to his meticulous observations, notably the mechanisms of apoptosis (programmed cell death) and the occurrence of cancer following abnormalities in this process. Nematodes are an ideal model for studying how apoptosis works in space in order to prevent the risk of cancerous pathologies in astronauts. They are associated, on the one hand, with exposure to dangerous radiation in space and, on the other hand, with possible changes in the normal functioning of apoptosis, which is responsible for eliminating cells modified by radiation.

This little worm is no stranger to space travel. During the STS-42 mission, carried out in 1992 on the Discovery shuttle, the nematodes were able to mate and reproduce over two generations without any apparent problems. But a few years later, the STS-76 mission carried out in 1996 aboard the Atlantis shuttle revealed something completely different! An abnormal mutation rate was observed in the nematodes, indicating for the first time a direct effect of cosmic rays on living organisms.

Worms survive the Columbia disaster

Following these experiments, it was proposed that nematodes be used in space as dosimeters to inform astronauts about the risks of mutations linked to cosmic rays. Nematodes were also on board the Columbia shuttle on February1, 2003, for the STS-107 mission. A tragic accident during the mission caused an explosion that destroyed the spacecraft and killed all seven crew members. However, scientists managed to find a 4 kg container holding the nematodes from the scientific expedition in the debris from Columbia that fell in Texas. They had survived. Protected in their box, they had already reproduced over several generations.

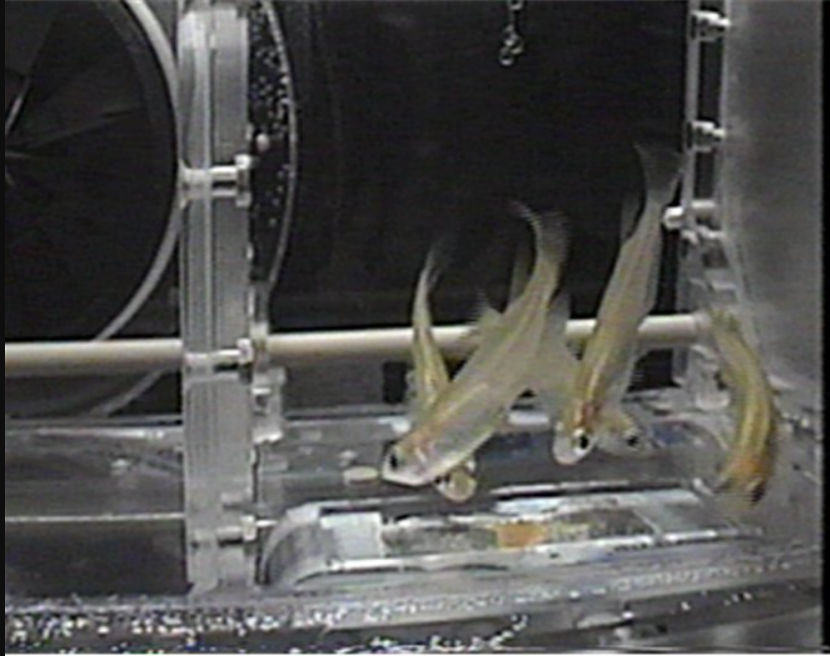

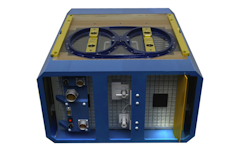

Let's return to the "Worm in Space" mission. On Monday, December 3, the Soyuz MS-11 capsule docked with the International Space Station carrying three astronauts and nearly 360,000 Caenorhabditis elegans nematodes. This experiment is dedicated to studying the 40% muscle loss that affects astronauts during long missions. This deficit is comparable to the muscle loss observed in men aged 40 to 80 during a natural process called sarcopenia.

The muscles of the nematode

Placed in special bags with their artificial food, the nematodes will remain there for six and a half days, after which they will be frozen and then returned to Earth for analysis in 2019. Several experiments will be conducted. One of them involves studying a control group of normal nematodes against another group of nematodes in which genes important for normal insulin function have been modified. This hormone is known to be linked to the mechanisms of senescence and aging through its effect on glucose utilization by tissues, particularly muscles. The use of genetically modified Caenorhabditis elegans with variations in glucose utilization will help to better define the involvement of insulin in the process of sarcopenia. This study aims to better understand why human muscles weaken with age in relation to the role of insulin.

Another experiment will seek to determine whether the expression of certain genes is modified in C. elegans by exposure to microgravity. During previous missions, it was observed that the expression of 150 genes in the nematode was reduced during a stay in space. This set of 150 identified genes will be studied again during this mission to see whether certain drugs can prevent or slow down muscle loss during space travel. An additional experiment will observe the functioning of the nematode's motor neurons, which trigger muscle contraction.

Other possibilities are opening up. One example is the development of automated systems for sending nematodes to other planets to study their fate over multiple generations. The general idea behind these space experiments is to better understand how humans live in space in order to prepare for missions to Mars. And, on Earth, to better understand how the human body works by observing the biological processes involved in the hostile environment that is space.![]()

Simon Galas, Professor of Genetics and Molecular Biology of Aging, CNRS – Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.