The radical uncertainty of global finance

Every year, the traditional summer break is accompanied by more or less relevant comments from economic observers on duty about the situation expected in September and the economic outlook for the last quarter of the year.

Roland Pérez, University of Montpellier

For this exercise, which sometimes falls under the category of seasonal topics, analysts scrutinize weak signals that could provide clues to support their predictions. In 2019, they will not need to collect such significant details, as the events, facts, and information observed in recent weeks are numerous and sufficiently consistent to allow for a well-documented analysis.

Most of these are linked to the uninterrupted stream of tweets from US President Donald Trump, who, week after week, attacks anything he perceives as hindering his "America first" slogan. After Iran, Mexico, Venezuela, the European Union, and many other countries, he is now attacking China again, a country with which he wants to reduce the structural trade deficit through the classic means of import taxes. But China is not Venezuela, and it has begun to retaliate, on the one hand by reducing some of its imports from the United States, and on the other by allowing its currency to slide on the foreign exchange markets.

These two events are cause for concern, as they signal the beginnings of a trade war, using the traditional instruments of customs tariffs and exchange rates. While we know how such a conflict begins, no one can predict its scale or outcome. Given that this is a confrontation between two global economic giants, we cannot rule out a lose-lose outcome for both parties, with significant collateral damage for the rest of the world.

Pre-election climate in the United States

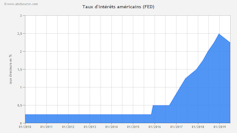

In this same context, we must consider events specific to monetary policy through the actions of central banks. Over the past dozen years—primarily in response to the 2008 global financial crisis – these central banks (Japan, then the United States and the EU) have implemented so-called "accommodative" financial policies, resulting in a sustained decline in key interest rates – to levels close to zero or even negative – and virtually unlimited repurchasing of bank debt ("quantitative easing").

The strong health of the US economy in recent years had allowed Federal Reserve (Fed) officials to begin returning to a more conventional stance, resulting in a gradual rise in key interest rates. However, this did not take into account President Trump's demand for a further cut in these rates.

This internal confrontation has so far resulted in a mini-cut (a quarter of a point) in the main interest rate, a concession by the current Fed chairman accompanied by a solemn warning from the four former chairmen expressing their concern about the central bank's independence from political power. No one can predict at this stage how the positions of the various parties will play out in the coming months, especially given the pre-election climate in which the country finds itself.

Financial markets, which detest this type of uncertainty, began to panic. In just a few trading sessions in August, the major indices lost a substantial portion of the gains they had made since the beginning of the year. Given that the year itself has seen an almost uninterrupted bull market since the 2008 financial crisis, the real question analysts are asking is whether these recent jolts mark the beginning of a lasting reversal of the financial markets' bull cycle or a blip linked to the current uncertainties surrounding public policy.

Excessive cash reserves

To attempt to answer this question without bias, it is necessary to examine the current situation of companies listed on these markets. Several observations are worth noting:

- Firstly, most of these large listed companies have benefited greatly from accommodative monetary policies, which have provided them with virtually unrestricted financing (bank loans or bonds) at very low cost, reducing their average cost of capital and changing their financing structures.

- However, the productive investments made in recent years by the large companies concerned have not been exceptional, falling within the average range of previous years. As a result, many companies and groups have abundant cash reserves awaiting investment.

- On the other hand, there has been a significant increase in share buybacks by listed companies, especially in the United States, where this type of transaction is less regulated than in the past. This has supported stock prices and increased leverage, or even double leverage when these share buybacks have been financed by additional debt.

- Financing facilities, combined with tax breaks granted in particular by the current US administration, have led to excellent net results, boosting stock market prices accordingly.

- These various factors combine and can result in the profile of a large listed company with good accounting and stock market performance and a balance sheet that includes both excess cash on the assets side and considerable debt on the liabilities side.

This situation, which many companies around the world would be happy with, is a cause for concern for us in terms of its significance, intrinsic quality, and sustainability. Accounting performance, and even more so stock market performance, is not directly linked to the economic model followed, but to the financial transactions carried out (use of debt, share buybacks, etc.); there is no guarantee that these favorable effects will continue in the future, unless they are maintained through monetary policies (for the cost of debt) or stock manipulation (for share buybacks).

Early warning signs of a recession

This summary analysis, which would obviously need to be refined by type of company and sector of activity, leads us—if we are to give our own diagnosis—to consider that the U.S. economy and its financial markets are indeed at the end of a bullish cycle that began with the bailout measures implemented after the 2007-2008 crisis to deal with this major crisis.

Signs that could be interpreted as precursors to a reversal in the global economic situation and its impact on the markets have appeared in a consistent manner:

- In terms of the economic climate, while indicators for US economic activity remain positive, concerns are emerging about the consequences of the trade war with China. These concerns prompted President Trump, in one of his customary about-turns, to postpone the new customs duties he had announced for several months, notably to protect consumers worried about price rises in the run-up to Christmas. In the rest of the world, the economic situation is more worrying, with indicators already deteriorating (Germany) or on the verge of doing so (United Kingdom).

- In terms of interest rates, we have seen a "rate inversion" between short- and long-term US Treasury bonds, which analysts interpret as a sign of an impending recession.

- On the stock markets, on several occasions, on the major American financial markets, it was the companies themselves, through their share buybacks, that acted as counterparties to other categories of agents (individuals, investment funds) who were "net sellers."

Investment funds seem aware of this worrying situation and many of them are adopting a wait-and-see approach, such as Warren Buffett's iconic fund, which has more than $120 billion in cash waiting to be invested.

These various effects combine, with some of them—such as the wait-and-see attitude of investment funds—being both a consequence of the other factors identified and a contributing factor.

The G7 with its back against the wall

Those responsible for economic and financial policy are aware of this risk of a reversal, but have little room for maneuver. Central banks are bogged down in their quantitative and monetary easing policies, which, according to consultant Jacques Ninet in his 2017 essay, are somewhat of a "black hole of financial capitalism." President Trump is also aware of this, but will do everything in his power to prevent a new financial crisis from erupting before the next political deadlines or, if such a crisis does occur, to shift the blame onto others (the Fed, China, etc.) and absolve himself of responsibility.

The next G7 meeting, scheduled for August 24-26 in Biarritz, will inevitably feature a heated exchange between these leaders. French President Emmanuel Macron, who will host the summit on behalf of France, will certainly attempt to outline a solution that is acceptable to all parties involved. He should be able to count on some G7 members and on the new leaders appointed, with his support, to head the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This is no sure thing, because in the financial sector more than any other, mutual trust between the actors responsible for implementing an action plan is essential to the success of those actions.![]()

Roland Pérez, Professor Emeritus, Montpellier Research in Management, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.