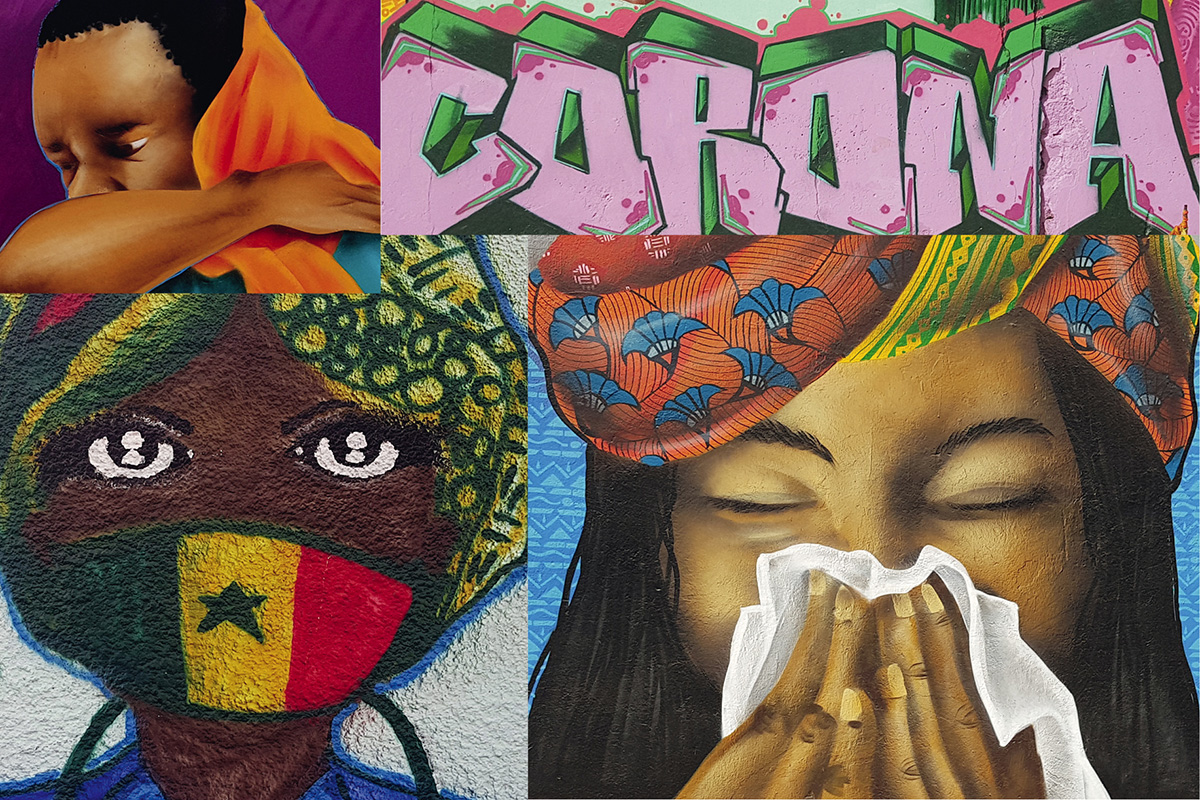

[LUM#13] Africa out of Corona

But what is happening in Africa? To answer this question, a serological test adapted to the African context is being rolled out in six countries. The aim is to gain a better understanding of how the virus is spreading on a continent that appears to be less affected than the West by coronavirus-related mortality, and thus to limit the harmful effects of an ill-adapted response.

In Africa, the COVID-19 epidemic began two or three weeks after it hit Europe. "We feared the worst, but with the exception of a few countries such as South Africa, we did not see the tsunami of serious hospitalizations and fatal cases observed in the West," reports Eric Delaporte, a researcher at the TransVIHMI* laboratory and a doctor specializing in infectious diseases at Montpellier University Hospital. How can this difference be explained? This is the focus of the ARIACOV project led by TransVIHMI and headed by this doctor, who is familiar with the African field, where he has monitored AIDS and Ebola epidemics.

Testing for coronaviruses in general

Many factors may explain this lower Covid mortality rate in Africa, foremost among which are demographics and the youth of a population that is inevitably less affected by severe forms of the disease. Other factors, particularly environmental ones, may also play a role, but as Eric Delaporte points out, "due to the limited diagnostic capacity in these countries, the first question is whether or not the virus is spreading and how widespread it is among the population in order to assess the dynamics of the epidemic, " explains the coordinator of the COVID South Task Force (ANRS, REACTing/Inserm, IRD).

To answer this initial question, a large-scale epidemiological survey was launched in six partner countries: Senegal, Ghana, Guinea, Cameroon, Benin, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. To carry out these screening campaigns, a serological test specifically adapted to the African context was developed. What makes it unique? It contains markers for different coronaviruses, not just SARS-CoV-2. "The aim is to be able to differentiate between people who have been infected with SARS or MERS, but also to add markers for winter coronaviruses and coronaviruses present in African wildlife [read the article "Bats under the radar "], explains the researcher .

Why look for coronavirus contamination, which is certainly present in wildlife but has never caused disease in humans? "Because humans may well have encountered these coronaviruses without developing disease or symptoms, but having developed antibodies." This encounter could be the source of a cross-immunity phenomenon and thus explain the low spread of the virus thanks to a kind of semi-protection. "It's only a hypothesis, but it needs to be studied," says Eric Delaporte.

Adapting the response to the actual epidemic

Several surveys will be conducted in different countries, with a minimum sample size of 1,500 people for each survey, and repeated every two months if possible in order to assess the dynamics of the epidemic. This essential assessment will be combined with a sociological analysis of the impact of the epidemic and lockdown on healthcare systems and society in general. In Africa, even more so than in the West, the side effects of these protective measures may prove to be more serious than the virus itself.

"Today in Africa, fewer people are being vaccinated, and access to antiretroviral and anti-tuberculosis treatments is more complicated," explains Eric Delaporte. This is due to fears of infection when visiting health centers, as well as border closures and air travel restrictions linked to lockdown measures. "Most of the drugs are generics manufactured in India. There is a risk of stock shortages, andthe WHO has estimated that a disruption in access to antiretroviral drugs lasting more than six months would result in several hundred thousand additional AIDS deaths," warns the doctor. Not to mention the consequences of lockdown on access to food in countries where a significant proportion of the population lives from hand to mouth.

These are obstacles that TransVIHMI scientists are already facing in sending the reagents needed for serological testing to Africa. The problem is that Western supplier countries, faced with managing their own emergencies, are preempting batches. This is a new situation for Eric Delaporte: "The Covid epidemic is global, unlike the epidemics we usually see in Africa. We must ensure that the emergency in the countries of the North is not managed to the detriment of Africa, which could then be left behind by the rest of the world."

Find UM podcasts now available on your favorite platform (Spotify, Deezer, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music, etc.).

* TransVIHMI Joint Research Unit (UM, IRD, INSERM U1175, Cheikh Anta Diop University (Dakar, Senegal), Yaoundé 1 University (Cameroon))