Yaacov Agam's work soon to be restored

For several weeks now, Yaacov Agam's work entitled "8+1 in Motion" has been undergoing restoration at the University of Montpellier. Acquired in 1969 by the University of Science in Montpellier, it adorned the lobby of its administrative building for nearly 36 years before being taken down in 2005. This important piece of UM's artistic heritage will soon be available for the public to enjoy once again.

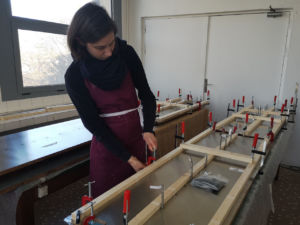

“This restoration is proving to be complex; it's quite a big project that will take us between one and two months of work,"says Rémy Geindreau, an art conservator-restorer specializing in technical, scientific, and industrial heritage. Together with his colleague Mélanie Paul-Hazard, who specializes in sculpture and contemporary art, they are patiently working in the historic premises of the medical school to restore a work that has been damaged by time.

“8+1 in Motion.” A work created in 1969 by Yaacov Agam. At the time, architects Philippe Jaulmes and Jean de Richemond were in charge of designing the new campuses for the science and arts faculties. As part of the“1% artistic” program, a scheme introduced in 1951 requiring the state to commission works of art to decorate public buildings, the two architects designed an ambitious decoration program and called on renowned artists such as Pol Bury, Yvaral, and Yaacov Agam.

Designed to play with light

A specialist in kinetic art, Yaacov Agam created a work designed to play with the effects of light and shapes. "It consists of 18 wooden panels covered with stainless steel plates arranged on a black-painted wall. The installation is 16 meters long in total. You might think that the panels are all identical, but they all have slight variations,"explains Rémy Geindreau.

Each panel features eight small black fins equipped with a mechanism that allows them to pivot, inviting the public to modify the compositions. On the reverse side of each fin, a spectrum of colors is reflected in the polished metal of the panel, creating different lighting effects depending on the position of the fins.

A work that has become unreadable

Unfortunately, over time,"56 fins (out of 144) have disappeared or been broken, and the stainless steel plates have become dirty and no longer reflect the colored spectrums. The entire kinetic dimension has been lost, and the work has become unreadable to the public,"says Audrey Théron, museum collection manager at the University of Montpellier. To prevent further damage, the work was taken down in 2005 and stored in various locations before arriving at the historic site of the Faculty of Medicine.

It took 15 years for this "8+1" to finally regain its movement. A long but necessary time for Audrey Théron, "the 1% artistic requirement obliges public institutions to maintain the works, which can sometimes be costly. Funding must be found."The cost of the first phase of restoration of this work amounted to €20,000, which was covered by the Regional Directorate for Cultural Affairs (DRAC).

Stop alterations

“The aim of this restoration is not to refurbish the work but to halt further deterioration in order to protect it and restore its legibility,” explains Mélanie Paul-Hazard. Even if they are distorted or scratched, there is no question of replacing the stainless steel plates or polishing them excessively. The goal is to preserve the physical integrity of the work and keep the original material. This requires compromises, such as leaving deep scratches.”

Each stainless steel panel was completely dismantled, dusted, cleaned, re-glued, and polished. The steel deformations were partially corrected and the edge strips were reconstructed where they had disappeared. The wing locking mechanisms were dismantled, de-seized where necessary, and treated against corrosion. The remaining wings were straightened, cleaned, and any impacts mitigated.

A real investigative effort

This work requires particular patience and precision when dealing with contemporary materials, as Rémy Geindreau points out: "We have fewer studies available for restoring stainless steel than for ancient archaeological metals." The difficulty is compounded when the restoration involves reconstructing missing elements, particularly the fins and their color spectrum. "The color sequence on the fins is not random; we have already identified eight recurring patterns. Restoration requires a real investigative effort to understand how the work was conceived."

Restorers are subject to another requirement: reversibility, as Mélanie Paul-Hazard explains. "Everything we add to the work must be removable. For example, we don't use epoxy glue, but a reversible glue that ages well." All of the work carried out by restorers is also documented in detail in a report. "It is important to clearly differentiate between what is original and what has been modified by successive restorers so that there is no misunderstanding about the work in a few decades' time."

An artistic heritage to rediscover

In a few months, the "8+1 in motion" should return to its original location on the Triolet campus and offer its colorful display to a new generation of students. This will be an opportunity to rediscover the University's artistic heritage, such as Pol Bury's Columns (1974), the frescoes and cladding of the university library by Yvaral (1972), the tapestry by François Desnoyer (1972), and Albert Dupin 's Seven Signs of Life(1970). Not to mention, of course, the new works that will enhance the brand-new Science Village.