What health measures are French people willing to accept?

Small or canceled New Year's Eve celebrations, scattered and isolated families, self-isolation, local, partial, or widespread lockdowns, curfews, travel restrictions, border closures, uncertainty about the reopening of certain sectors: France, like many other countries around the world, has faced a series of restrictions in an attempt to contain the epidemic.

Thierry Blayac, University of Montpellier; Bruno Ventelou, Aix-Marseille University (AMU); Dimitri Dubois, University of Montpellier; Marc Willinger, University of Montpellier; Phu Nguyen-Van, University of Strasbourg and Sébastien Duchêne, University of Montpellier

While each type of measure/restriction has its own effectiveness in controlling the epidemiological dynamics, they must also be evaluated in terms of their acceptability to the population.

At a time when decision-makers are considering re-evaluating restrictive measures to prevent a resurgence of the epidemic, public preferences should be taken into account in public decision-making.

This is particularly true after many months of effort and the implementation of new measures in recent weeks in many European countries.

Distinct attitudes

Our team of behavioral economics researchers quantified the degree of resistance or acceptability of a population to various strategies for combating the COVID-19 epidemic. Our findings were published in an article in the international scientific journal The Lancet Public Health.

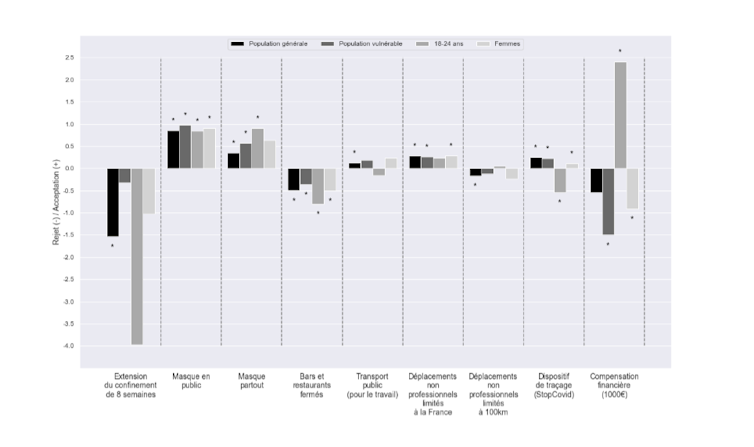

The results of the study show that mask wearing, transportation restrictions, and digital tracking are relatively well accepted.

On the other hand, closures of restaurants and recreational venues, as well as excessive restrictions on leisure travel, are much less acceptable. Analyses of population subgroups (clinical vulnerability, age groups, gender) also show that the acceptability of certain strategies depends on personal characteristics.

In particular, the young population differs quite significantly from others in terms of preferences for anti-COVID-19 policies and demands for monetary compensation, suggesting the need for a tailored "menu" of anti-COVID-19 policies based on distinct attitudes.

Assessing the preferences of the population

The study uses a preference revelation method, the " Discrete Choice Experiment," to assess the population's preferences for various combinations of public policies to control COVID-19 epidemics.

Between May 4 and 16, 2020, at the end of the first lockdown in France, our team conducted an online survey of a representative sample of the French population.

One of the objectives of the survey was to assess acceptance of restrictive measures among the main anti-COVID strategies discussed by the French government in early April for the period following lockdown.

The graph below shows a ranking of preferences for the entire population and for certain subgroups, defined according to their clinical vulnerability, age, or gender.

Authors, Author provided

A necessary evil

Masks, restrictions on public transportation, and digital tracking (via an optional cell phone app) were deemed acceptable by the general population, provided that the restrictions on each of these aspects remained reasonable. Thus, wearing a mask is much less acceptable when it is associated with the word "everywhere."

Conversely, additional weeks of lockdown, the closure of restaurants and bars, and excessive restrictions on leisure travel (less than 100 km) were not considered acceptable.

Overall, these results indicate that the French population has relatively well accepted the restrictive measures that followed the first lockdown, viewing them as constraints, but also as a "necessary evil," to be weighed against the risk of another lockdown, a possibility that was perceived very negatively.

Rejection of additional weeks of lockdown was more than proportional: the longer the additional lockdown period, the greater the intensity with which it was rejected.

Vulnerable people are more tolerant

Compared to the general population, clinically vulnerable individuals, i.e., those who report suffering from a chronic illness, showed greater tolerance for lockdowns, greater acceptance of mask wearing, and less resistance to restaurant and bar closures.

However, these differences were small, indicating either a form of altruism on the part of non-vulnerable individuals toward vulnerable individuals, or a low degree of uniqueness among vulnerable individuals in their attitudes toward risk.

Young people (aged 18-24) were the most discordant group, perhaps because they are less concerned about health risks than older groups (even though the medical risk is not zero for young people, and remains significant for the older people with whom they are in contact).

In our survey, among the various attributes, we proposed financial compensation to offset the burden of restrictive policies. Our analyses showed that young people were clearly in favor of this proposal, unlike other segments of the population, who clearly rejected it.

From this result, we can deduce that financial incentives could be an effective tool when targeted at young people, and that they are likely to encourage young people to be more accepting of restrictive anti-COVID policy options.

This solution would amount to applying a compensation mechanism such as a Pigou tax, which is already used in other areas of public economics. According to Arthur Pigou, an English economist from the early 20th century, the principles of "welfare economics" can lead to taxing—or compensating—individuals who have negative—or positive—external effects, in order to bring them back to behaviors that are more optimal for society.

Therefore, understanding how people within a population rank different COVID-19 prevention measures is essential for designing appropriate programs and measures, a challenge that many countries in the Northern Hemisphere face every day while waiting for a vaccine to become widely available.

Our survey therefore highlights the need for COVID policies that are more attuned to people's sensitivities.

It proposes ways, in particular through compensation for young people, to make control policies more acceptable, taking into account the preferences of different segments of the population, and to prevent some of them from refusing to comply with the measures, thereby spreading the risk of an epidemic throughout society as a whole.![]()

Thierry Blayac, Professor of Economics, Montpellier Center for Environmental Economics (CEE-M), University of Montpellier; Bruno Ventelou, CNRS-AMSE Researcher, Economics, Public Health, Aix-Marseille University (AMU); Dimitri Dubois, Behavioral Economics, Environmental Economics, Experimental Economics, University of Montpellier; Marc Willinger, Professor of Economics, behavioral and experimental economics, University of Montpellier; Phu Nguyen-Van, CNRS Research Director in Economics, University of Strasbourg and Sébastien Duchêne, Senior Lecturer in Economics, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.