Pension reform: what impact on volunteering?

Pension reform will have an impact on future retirees, public finances and, we forget, probably on associations too.

Andréa Gourmelen, University of Montpellier and Ziad Malas, University of Toulouse III - Paul Sabatier

Younger retirees are a group whose available time and state of health are conducive to above-average volunteer involvement.

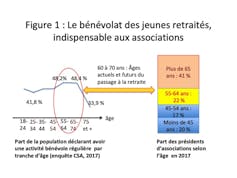

This can be seen in the high percentage of volunteers among 55-74 year-olds (48.3%), in the greater amount of time spent volunteering (58% of over-65s involved in an association devote more than five hours a week to it), and in the essential involvement of association leaders, as shown in figure 1 (created on the basis of work by Viviane Tchernonog and Lionel Prouteau).

Andrea Gourmelen/Ziad Malas, Author provided

While many points of the future law remain to be specified, we already know its main principles and part of the implementation schedule: arrival in the hemicycle from Monday February 17 and final vote before the end of the parliamentary session by summer 2020.

Towards a drying up of the French associative breeding ground?

Some of these principles may contribute to a drying up of the pool of volunteers in associations. In addition to discussions on the pivot age, the future law will give employees greater freedom to choose their retirement age, and encourage late retirement. If retirement starts later, logically this should mean less time available for volunteering.

On a statistical basis, this reasoning is debatable, given the increase in life expectancy and the less marked increase in healthy life expectancy.

But the logic of shifting life stages comes up against the inertia of perceptions and affects associated with age and time remaining. So, taking into account what researchers call ultimate temporal pressure (UTP) - the pressure we feel as time passes - also becomes a time that remains. In fact, it's one of the keys to understanding retirees' commitment to volunteering.

Future retirees under the universal scheme are now no more than 45 years old, and are probably not yet thinking about what they'll be doing when they retire... Or what they'll be doing by the time they retire? The economic and social situation will also have changed the values and priorities of future generations of retirees.

For all that, it is possible to envisage possible scenarios that will start to affect volunteering 10 years from now, based on the profiles of current retired volunteers that we studied in a previous article, published in 2014. These profiles are characterized in particular by their ultimate time pressure and generativity: that is, their degree of concern for future generations.

Will posterity-minded volunteers work longer?

These profiles account for around 38% of retired volunteers, who appear to be strongly affected by negative feelings about the end of life and the time left to live. They are afraid of approaching death and aging. For them, volunteering is a way of countering the passage of time, of making themselves indispensable in order to gain a certain recognition.

Thus, they seek first to build a reputation during their lifetime, and then to transform this reputation into a popularity that will endure beyond their death. Management positions and those involving public prominence seem to particularly echo their motivations.

With the current reform, their careers are likely to become longer. So, to match their ambitions, they are likely to opt for professional choices rather than volunteering as a "second career". The new financial incentives will reinforce this choice. Also, getting involved in an association at a later stage would leave them less time to get involved and move up the association's hierarchy, which could lead to frustration for these people and a void at hierarchical level.

We can therefore expect them to give greater priority to professional activity (working as long as possible) in order to gain recognition more quickly, as retirement can be seen as a marker of ageing, which makes them anxious.

Guilty volunteers: on the wane?

These retirees volunteer out of a sense of moral duty and true self-sacrifice. Feeling guilty of having had a good life or of having been privileged, their generativity leads them to get involved in society as much as they can. The self disappears, to the benefit of others, of the community.

Volunteering becomes a way of giving back to society. Isn't there a risk that this profile, which accounts for around 13% of current retired volunteers, will disappear among future generations of retirees? Will this self-sacrifice, linked to the need to give back to society what it has given us, still be as strong if working longer and the fear of a lower standard of living lead us to think that society is taking more from us than it is giving us?

Generational guilt is thus likely to be replaced by individual guilt (the feeling of having done better than others of one's generation), at least for the 1975-1985 generation, corresponding to the transition phase between pension schemes.

Indeed, this generation may feel sacrificed, and therefore unprivileged compared to the baby-boomer generation (still a large one, comprising almost 24% of the French population). The reform could thus widen the generation gap and reinforce the boomers' image as privileged, as is the case with the "OK boomer" phenomenon on social networks.

This is likely to lead to difficulties in areas where this profile appears to be the most suitable: charities or social assistance functions in the voluntary sector, such as listening to people in difficulty, helping them reintegrate into society or distributing food.

Hedonists and affections: towards new temporal arbitrations?

These "hedonistic and affective" profiles alone account for around half of all retired volunteers. They bring together retired people who have freely chosen volunteering as an entertaining activity, enabling them to discover new opportunities while forging human links. Not necessarily concerned about the future of the next generation, they nevertheless enjoy working with a variety of people in their volunteer activities. For them, it's all about making the most of the time they have left to live. They have few negative feelings about time being short.

At first glance, pension reform seems to have less impact on these profiles, as the pleasure associated with volunteering seems so strong. However, a later retirement date may lead to a greater sense of pressure about the time left to live when one stops working. This could lead to an increase in negative feelings about the time remaining (stress, bitterness), and thus more arbitration about the allocation of this remaining time. A withdrawal into family or leisure activities to the detriment of voluntary work could be envisaged.

Pxhere, CC BY

From "young retirees" to "old working people

While the reform will enable those who have had strenuous jobs to retire earlier (physical, high-risk jobs, staggered working hours), and while the notion of strenuousness is still under study, it should be borne in mind that these jobs generally involve short studies.

However, retirees involved in associations generally have a high level of education (compared to the average level of education of their generation). As a result, future retirees potentially interested in volunteering are likely to be older and older (having studied for a long time, they may not be concerned by the notion of arduousness), and may end up thinking that they are no longer old enough to volunteer.

Does this mean that associations should target individuals who are allowed to retire earlier? Not necessarily, as past working conditions could have an impact on the time left to live in good health as perceived by the latter, leading to reasoning along the lines of: "I'm too tired, too damaged to work and therefore... to do voluntary work".

So, rather than targeting "young retirees" who may perceive themselves as "too old" or "not healthy enough" depending on their previous occupation, associations should perhaps focus on active seniors. This would make it possible to anticipate their objections.

The need for thoughtful commitment

For some years now, France Bénévolat has been stressing that successful volunteering is the result of a well-considered commitment. And what better way to ensure a well-considered commitment than to prepare for it in advance of retirement? What's more, we know that among working people, the over-50s are the most likely to volunteer, mainly because they don't have young children to look after.

We could also add that between the age of 50 and retirement, there are fewer financial constraints. So, provided that the anxiety linked to the amount of pensions is alleviated, we have here a population that will be receptive to volunteer commitment, a commitment that will continue after retirement and be accompanied by another key resource for associations: the donations.![]()

Andréa Gourmelen, Senior lecturer in management science (marketing), University of Montpellier and Ziad Malas, Senior Lecturer in Management Sciences, University of Toulouse III - Paul Sabatier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read theoriginal article.