Reuse of wastewater: what will change with the new European regulation?

Reusing wastewater to save fresh water is one of the benefits of what is known as "reuse." This approach is an essential lever in a context where global warming is increasing pressure on water resources.

Julie Mendret, University of Montpellier

However, this lever is rarely used in France, where only 0.6% of wastewater is treated. This is negligible compared to other European neighbors, such as Italy, which treats 8% of its wastewater, and Spain, which treats 14%. Why is our country lagging behind? This French phenomenon can mainly be explained by a lack of public awareness and very strict regulations.

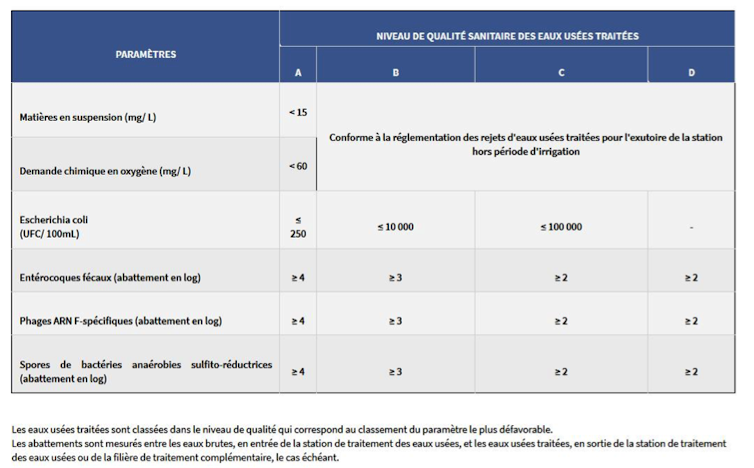

The reprocessing and reuse of treated wastewater is regulated in France by two ministerial decrees from 2010 and 2014. These regulations define four levels—A, B, C, or D, from best to worst—each with its own water quality requirements and authorized and prohibited uses. For example, crops that are eaten raw can only be irrigated with water of quality level A.

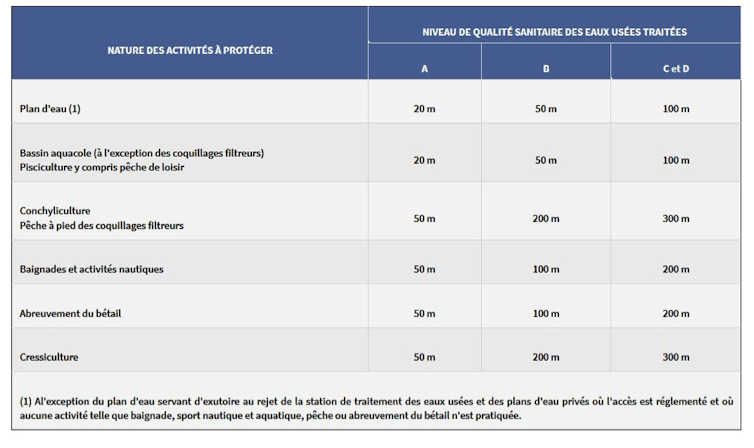

Added to this are usage constraints depending on the irrigation technique, such as wind speed, minimum safety distances from homes or waterways, public information, etc.

Regulatory barriers

While these strict regulations are necessary for health and environmental reasons, the constraints inherent in their application complicate the preparation of applications and even jeopardize projects.

Several of these projects were abandoned due to constraints relating to implementation (preparation of documentation, land type constraints, specific requirements for sprinkler irrigation, etc.) and operation (traceability requirements, water quality monitoring, irrigation program management, etc.).

A new European regulation

How can we prevent these projects from falling apart in the face of regulatory obstacles? This is the subject of the new European regulation of June 5, 2020, on the reuse of wastewater, which aims to promote reuse by harmonizing the rules of application at the European level.

The European Parliament thus reiterates that these new rules:

"aim to ensure that treated wastewater is reused more widely in order to limit the use of water bodies and groundwater. The decline in groundwater levels, due in particular to agricultural irrigation, but also to industrial use and urban development, is one of the main threats to the EU's aquatic environment."

Stated objective: to increase reuse from 1.7 billion cubic meters per year to 6.6 billion, which would reduce water stress in the EU by 5% by 2025.

The European regulation only concerns agricultural irrigation—other uses remain the responsibility of the Member State; Member States have three years to bring their facilities into compliance.

More flexible than the French framework

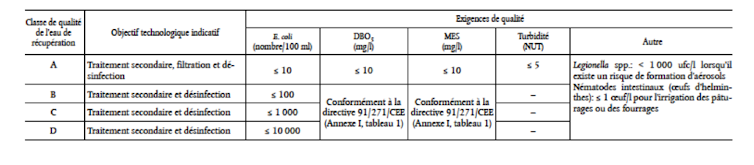

This new regulation is more flexible than the current French framework: the four water quality classes are maintained—with stricter microbiological thresholds (for the Escherichia coli criterion, French quality class A corresponds to quality class C in the new regulation)—but performance targets are no longer required, except for quality class A. To compensate, the frequency of health checks – which varies according to the water class – has been increased.

Another major advance is that mandatory usage restrictions related to distance, soil type, and wind speed have been eliminated. To replace them, "barriers" have been introduced—such as additional treatment—allowing quality criteria to be adapted according to risk.

The operator of the wastewater treatment plant must propose a risk management plan identifying the risks and the measures implemented to manage them (replacing the French rules of use that have been mandatory until now). Once validated, this plan will enable the operator to obtain an operating permit specifying, among other things, the quality class of the water produced and the authorized agricultural use.

The risk management plan, drawn up by the wastewater treatment plant operator, is therefore one of the cornerstones of this new regulation.

It allows each project to be considered on a case-by-case basis and provides greater flexibility in setting up reuse projects. It also includes a public awareness component, encouraging the publication of certain data (recycled water quality, test results, etc.) in order to reassure consumers and improve social acceptance of reuse, which is already growing rapidly. Today, 83% of French people say they are willing to drink drinking water produced from wastewater.

EUR-Lex

Harmonization and questions

In some respects, the European regulation of June 5, 2020 represents real progress. Practices and quality standards will be the same in all Member States, with usage restrictions tailored to actual risks and greater transparency for consumers.

However, this new regulation only considers one use, irrigation; it is hoped that this will eventually lead to the democratization of other uses in France, such as irrigation of golf courses and parks, firefighting, and groundwater recharge.

However, very high quality requirements can lead to additional costs for upgrading facilities, particularly if an additional treatment stage needs to be added. In some cases, this obstacle cannot be overcome without public funding.

Finally, this regulation does not mention certain categories of pollutants that are of great concern (microplastics and pharmaceutical micropollutants, for example), which worry consumers and for which advanced treatments must generally be put in place.![]()

Julie Mendret, Senior Lecturer, HDR, University of Montpellier

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Readthe original article.